By- Dr Santosh Giri, Livestock consultant, Varanasi,UP.

Bloat is an over distention of the rumen and reticulum with the gases of fermentation. Bloat can be dived into primary and secondary, primary is also known as legume, dietary or frothy bloat , It generally occurs up to 3 days after animals begin anew diet, moreover certain legumes such as alfalfa ,ladino clover, and grain concentrates ,promote the formation of stable foam , furthermore secondary tympany is caused by a physical or functional obstruction or stenosis of esophagus resulting in failure to eructate .Vagus indigestion or other innervations disorders, esophageal papilloma, lymphosarcoma ,and esophageal foreign bodies are examples of causes of secondary tympany . Foam mixed with rumen contents physically blocks the cardia preventing eructation and causing the rumen to distend with gases of fermentation. . Recurrent rumen tympany is frequently a sign of digestive disease in young calves ,the tympany is usually moderate and results from accumulation of free gas in the reticulorumen . In adult animals, free-gas bloat is less frequent and usually more acute because disturbances of the adult rumen tend to be more rapid and severe .

Prodigious volumes of gas are continually generated in the rumen through the process of microbial fermentation. Normally, the bulk of this gas is eliminated by eructation or belching, which ruminants are spend a lot of time doing. Certainly, anything that interferes with eructation will cause major problems for a ruminant. The problem, of course, is called ruminal tympany or, simply, bloat.

Pathogenesis

Bloat is the overdistension of the rumen and reticulum with gases derived from fermentation. The disorder is perhaps most commonly seen in cattle, but certainly is not uncommon in sheep and goats.

Two types of bloat are observed, corresponding to different mechanisms which prevent normal eructation of gas:

1. Frothy bloat (primary tympany) results when fermentation gases are trapped in a stable, persistent foam which is not readily eructated. As quantities of this foam build up, the rumen becomes progressively distended and bloat occurs. This type of bloat occurs most commonly in two settings:

• Animals on pasture, particularly those containing alfalfa or clover (pasture bloat). These legumes are rapidly digested in the rumen, which seems to results in a high concentration of fine particles that trap gas bubbles. Additionally, some of the soluble proteins from such plants may serve as foaming agents.

• Animals feed high levels of grain, especially when it is finely ground (feedlot bloat). Again, rapid digestion and an abundance of small particles appear to trap gas in bubbles. Additionally, some species of bacteria that are abundant in animals on high concentrate rations produce an insoluble slime that promotes formation of a stable foam.

Bloat on pasture is frequently associated with “interrupted feeding” – animals that are taken off pasture, then put back on, or turned out on pasture for the first time in the spring.

2. Free gas bloat (secondary tympany) occurs when the animal is unable to eructate free gas in the rumen. The cause of this problem is often not discovered, but conditions that partially obstruct the esophagus (foreign bodies, abscesses, tumors) or interfere with rumenoreticular motility (i.e. reticular adhesions, damage to innervation of the rumen) clearly can be involved.

Another cause of free gas bloat that should be mentioned involves posture. A ruminant cannot eructate when lying on its back, and if a cow falls into a ditch and is unable to right itself, she will bloat rapidly. Ruminants that are to undergo surgery in dorsal recumbancy should be starved for 12 to 24 hours prior to surgery, or by the time the surgeon is ready to make the incision, the abdomen will already be distended.

Regardless of whether bloat is of the flothy or free gas type, distention of the rumen compresses thoracic and abdominal organs. Blood flow in abdominal organs is compromised, and pressure on the diaphragm interferes with lung function. The cause of death is usually hypoxia due to pulmonary failure.

Clinical Signs

Clinical findings

Primary bloat is a common cause of sudden death (or found dead) in cattle, findings include:

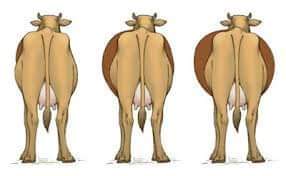

1. Obvious distension of the rumen occurs quickly, sometimes as soon as 15 minutes after going on to bloat producing pasture, and the animal stop grazing. The distension is usually more obvious in the upper left paralumbar fossa but the entire abdomen is enlarged.

2. There is discomfort and the animal may stand and lie down frequently, kick at its abdomen and even roll.

3. Frequent defecation and urination are common.

4. Dyspnea is marked and is accompanied by mouth breathing, protrusion of the tongue, salivation and extension of the head.

5. The respiratory rate is increased up to 60/min.

6. Ruminal contractions are usually increased in strength and frequency in the early stages and may be almost continuous, but the sounds are reduced in volume because of the frothy nature of the ingesta. Later, when the distension is extreme, contractions are decreased and may be completely absent.

Secondary bloat

1. In secondary bloat, the excess gas is present as a free gas cap on top of the ruminal contents.

2. There is usually an increase in the frequency and strength of ruminal movements in the early stages followed by atony.

3. Passage of a stomach tube or trocarization results in the release of large quantities of gas and subsidence of the ruminal distension.

4. In both severe primary and secondary bloat there is dyspnea and a marked elevation of the heart rate up to 100-120/min in the acute stages. A systolic murmur may be audible, caused probably by distortion of the base of the heart by the forward displacement of the diaphragm.

Pathology

Animals that die from bloat have rather characteristic lesions, including congestion and hemorrhages in the cranial thorax, neck and head, and compression of the lungs. Pressure from the distended rumen leads to congestion and hemorrhage of the esophagus in the region of the neck, while the esophagus in the thorax is pale. This demarcation between congestion and pallor seen in the region of the thoracic inlet is called the “bloat line”. Usually, the liver is also pale because of displaced blood and interruption of blood supply.

Obvious distension of the rumen is certainly observed in animals that die of bloat, but also occurs rapidly after death from almost any cause in ruminants, and is not a useful diagnostic lesion.

Treatment and Control

Bloat is a life threatening condition and must be relieved with haste. For animals in severe distress, rumen gas should be released immediately by emergency rumenotomy. Insertion of a rumen trochar through the left flank into rumen is sometimes advocated, but usually not very effective unless it has a large bore (i.e. 1 inch), and is often followed by complications such as peritonitis.

In less severe cases, a large bore stomach tube should be passed down the esophagus into the rumen. Free gas will readily flow out the tube, although it may need to be repositioned repeatedly to effectively relieve the pressure. In the case of frothy bloat, antifoaming medications can be delivered directly into the rumen through the tube; the animal should then be closely observed to insure that the treatment is effective and the animal begins to belch gas, otherwise a rumenotomy may be indicated.

A variety of antifoaming agents have been used to relieve frothy bloat. These include common items such as vegetable oils (corn, peanut) or mineral oil, which are administered in 100-300 ml volumes to cattle. A number of effective commercial products are available that include such agents as polaxalene (a surfactant) or alcohol ethoxylate (a detergent).

Control of bloat relies on management coupled sometimes with medications, but despite best efforts, is rarely totally effective. Also, some of the techniques advocated may be applicable to small herds, but are too labor intensive to use with large herds. Many of the techniques used are based on reducing the rate of fermentation that occurs in the rumen. Examples of control strategies include:

• maintain pastures that have grasses mixed with legumes such as alfalfa

• feed animals hay before turning out on bloat-inducing pastures

• in feedlots, feed roughage such as straw or grass hay in addition to concentrate

• for animals on high grain rations, the grain should be cracked or rolled rather than finely ground

• apply antifoaming agents prophylactically, either by drenching individual animals, incorporating into feed, or spraying on small pastures

Treatment

1. Emergency rumenotomy or using a sharp knife, a quick incision 10-20 cm in length is made over the midpoint of the left paralumbar fossa through the skin and abdominal musculature and directly into the rumen to relief the accumulated cases and used for administration of drugs.

2. Trocar and cannula have been used for many years for the emergency release of rumen contents and gas in bloat.

3. Promote salivation For less severe cases, may be advised to tie a stick in the mouth like a bit on a horse bridle to promote the production of excessive saliva, which is alkaline and may assist in denaturation of the stable foam.

4. Passage of a stomach tube of the largest bore possible is recommended forcases in which the animal’s life is notbeing threatenedin free gas bloat, there is a sudden release of gas and the intraruminal pressure may return to normal.

5. Careful drenching with sodium bicarbonate (150-200 g in 1 L of water) or any nontoxic oil in cases of frothy bloat to decrease the surface tension and relief of distension.