FOOT ROT IN CATTLE- THERAPEUTIC MANAGEMENT

FOOT ROT IN CATTLE

(foot rot, interdigital necrobacillosis, interdigital pododermatitis, acute foot rot, and foul in the foot)

There are many things that can cause lameness in cattle. One of the most common is the condition called interdigital necrobacillosis or foot rot. (It is also known as foul, foul in the foot, infectious pododermatitis and interdigital phlegmon.) Foot rot in cattle is caused by Fusobacterium necrophorum, which may act alone, or in concert with a few other bacteria, including Bacteroides melaninogenicus, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia Coli, Actinomyces pyogenes and the newly blamed Porphyromonas levii. Dichelobacter (Bacteroides) nodosus, the causative agent of the highly contagious foot rot seen in sheep, can cause a superficial surface inflammation in cattle, allowing the entrance of the pathologic F. necrophorum.

Foot rot in cattle is caused by the anaerobic bacteria Fusobacterium necrophorum. Fusobacterium necrophorum is ubiquitous in the environment of cattle as it is a normal inhabitant of the intestine and faeces. [1] It can also remain dormant in the soil for several months.[2] The organism contaminates areas where cattle congregate.

Foot rot in cattle should not be confused with foot rot in sheep. The two diseases are different and cross infection between the two species is not believed to occur. Foot rot in sheep requires not only a virulent strain of Dichelobacter nodosusto be present, but also Fusobacterium necrophorum.

Interdigital phlegmon is occasionally confused with interdigital dermatitis because both conditions are associated with lesions of the interdigital skin. However, interdigital phlegmon is an infection of the interdigital skin that extends into the deeper underlying soft tissues of the foot. The disease is characterized by swelling of the foot, severe lameness, and in most cases a necrotic lesion of the interdigital skin. Although occurrence is generally sporadic, epidemics are known to occur in confinement-housed cattle. Secondary complications associated with foot rot include infectious arthritis of the distal interphalangeal joint, necrotic tendinitis, navicular bursitis, and abscessation of the retro-articular space.

Distribution————

Foot rot has been reported from many countries. The disease is particularly prevalent in temperate climates with a moderate rainfall and relatively high cattle population density.

Most cases of foot rot result from the organisms entering the subcutaneous tissue through interdigital skin, likely as the result of traumatic damage or the action of noxious agents in slurry. Commensal organisms of the skin may also play a role.

Signalment———-

Any breed, age or sex of cattle can be affected.

Clinical Signs————–

Foot rot is characterized by swelling of the foot, the presence of a necrotic lesion in the interdigital skin, and severe lameness. The highest incidence occurs in rear feet, and normally only one foot is affected. Inflammation of the foot is generally symmetrical and frequently extends to the region of the fetlock. Swelling of the foot is usually sufficient to result in separation of the digits. Body temperature is normally elevated (39°-40° C) with feed intake, and performance significantly reduced. Closer inspection of the foot and interdigital skin usually reveals a swollen necrotic lesion of the skin that may extend the length of the interdigital cleft. This necrotic lesion yields exudates with a characteristic foul odor that is one of the diagnostic features of this disease

The first sign of foot rot is acute swelling of the tissue between the toes and swelling evenly distributed around the hairline of usually just one hoof. Often, the animal may be running a fever at this time. Acute foot rot appears to be exquisitely painful, the cattle are often dead lame on one foot, with reluctance to move, and increased recumbency. Calves are usually easy to diagnose from a distance, as their lighter body weight allows them to move about relatively well on three legs, rather than remaining recumbent. Also, their smaller, more delicate features may allow easier detection of the tell-tale swollen foot. Eventually, the interdigital skin cracks open, revealing a necrotic, vile-smelling core of dead tissue. Untreated, the infection may cause swelling to extend up the foot to the fetlock or higher. More critical, severe cases may invade the deeper structures of the foot, including the bones, tendons and joints, resulting in permanent damage Other conditions that may resemble foot rot include interdigital dermatitis, sole abscesses, sole abrasions, infected corns, fractures, joint infections (septic arthritis) and tendonitis. These conditions usually involve only a single claw of a single foot and not the areas of skin between the toes. Digital dermatitis (hairy heel warts) usually occurs on the back of the foot, just above the bulb of the heels and may progress up to the dewclaws. Large hairy heel warts are unmistakable in the peculiar, large horny “hairs” that grow from the chronically inflamed skin. They require only topical therapy, while foot rot, unless caught very early and a very mild case, requires systemic antibiotics.

Once F. necrophorum has entered the interdigital space, extensive cellulitis develops. The inflammatory oedema between the claws pushes them apart, stretching the interdigital ligaments and causing considerable pain. The skin between the claws fissures then sloughs. A common complication is septic arthritis of the distal interphalangeal joint.

Signs are usually a sudden onset generalised lameness of varying degree. Animals are usually pyrexic. The affected leg will appear swollen and erythematous and the animal may be noted to be shifting its weight. If chronic, there may also be evidence of disuse atrophy in the affected limb. The animal may have reduced weight gain or weight loss and have a decreased milk yield.

On closer examination of the foot, it will appear hot, moist, erythematous and have a foul odour. There may be skin necrosis and sloughing of the affected area and a purulent discharge may be present. The swelling may have caused the two digits to separate, and the cleft between the claws may appear to be larger than normal.

Diagnosis————-

Clinical signs plus physical examination of the foot will lead to a presumptive diagnosis of the disease.

Radiography is not useful in most instances, but is essential in cases failing to respond to treatment and when either septic pedal arthritis or a retroarticular abscess is suspected.

The organism can be isolated and cultured in a laboratory, but this is not usually required for diagnosis.

Exclusion of differential diagnoses such as retroarticular abscessed is important. The characteristic of this condition is that swelling occurs around one digit only, which is different to foot rot. Severe diseases such as Foot and Mouth should also be eliminated, particularly notifiable disease.

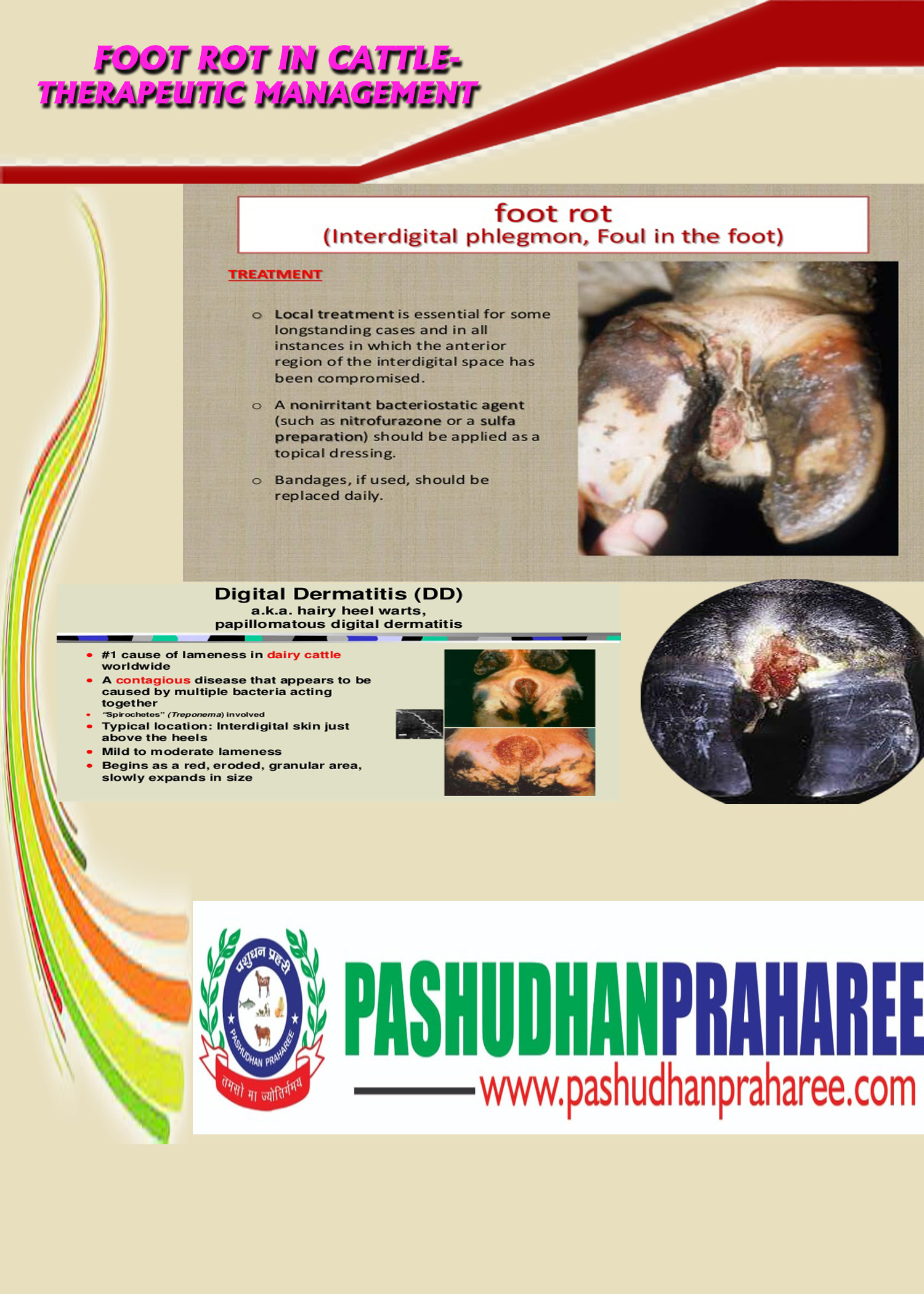

Treatment—————–

Treatment is usually straightforward once the diagnosis has been confirmed. Probably length of treatment time is more critical than which antibiotic is used. A minimum of 3-5 days of antibiotic therapy will be necessary and in severe or resistant cases, longer than that. A number of injectable antibiotics are usually highly effective against the foot rot organism. Treatment should always begin with cleaning and examination of the foot. If extremely mild and early, topical treatment with antibiotic ointment or soaks may suffice; however, close observation must continue to make sure the infection is responding to the treatment. Sometimes “flossing” between the toes with a clean rope or twine will help to remove some of the dead tissue. Injectable antibiotics are the mainstay of treatment for foot rot. They need to be used at a high enough dose for a long enough period of time to cure the infection. This will require adequate blood levels for a minimum of 3-5 days and at least several days past apparent cure (the animal is sound, not limping, without swelling and without fever) Deep infection of the foot may occur as a result of untreated or severe cases of foot rot. Involvement of the joints, tendons or bones of the foot will not be correctable with foot trimming procedures and often will result in permanent lameness ultimately requiring slaughter. Unfortunately, the dorsal pouch of the distal interphalangeal joint is very close to the interdigital skin and can become infected due to foot rot. The disease is not to be taken lightly. Affected animals should be kept in dry areas until healed. This accomplishes 2 things; speeds healing in the infected animals and limits environment contamination. Foot rot that progresses to a severe infection may require salvaging for slaughter, claw amputation or in extremely valuable animals, claw salvaging surgical procedures.

If treated, most cases respond very rapidly, usually with very little after effect. Recurrence will occur occasionally. Natural immunity appears to inhibit reinfection for at least six months.

Suitable antibiotics for treatment of the condition include penicillin G, oxytetracycline, sulfadiazine/trimetroprim, sulfadimethoxine and tylosin. All should be given by injection for three days as topical therapy is not effective. Always follow withdrawal guidelines.

Intravenous infusion via the digital vein with a suitable antibiotic is the most effective way to treat the most advanced cases.

If the skin of the interdigital space has sloughed, topical treatment is also essential. This is particularly important if a secondary lesion appears to be starting in the dorsal region of the interdigital skin. The wound should be cleaned with soapy water, then thoroughly dried and a topical dressing such as an antibiotic paste should be applied. The lesion must then be protected for a few days minimum.

The administration of parenteral antibiotics early in the course of the disease is necessary for optimal results from therapy. In fact, antibiotic selection is probably less important than treatment duration and time to initiation of therapy. Sulfadimethoxine given by intravenous injection at the rate of 55 mg/kg is effective. Also, procaine penicillin G (22,000 IU/kg body weight) and oxytetracycline (10 mg/kg) by either an intramuscular or subcutaneous route (according to label instructions) are frequently recommended. Ceftiofur at the rate of 1 to 2 mg/kg of body weight at 24-hour intervals for 3 consecutive days offers effective therapy without the threat of antibiotic residue when used according to label directions. A few newer, long-acting products are not only effective but also offer the convenience of single-dose treatment. Noticeable improvement (i.e., reduced swelling and improved gait) should be observed within 3 to 5 days of the onset of treatment.

Local treatment of the lesion should include cleaning and careful débridement of necrotic tissue in the interdigital skin. Because this can be a painful procedure, xylazine or preferably intravenous regional anesthesia is recommended. Once the lesion has been cleaned and all necrotic tissue removed, it may be treated with a topical antimicrobial ointment and secured with a bandage, if desired. Bandages should be applied carefully (not too tight) so that they do not cause additional damage to the interdigital skin as a result of the migration or contraction of bandage material into the interdigital space. When a bandage is used, it should be removed in approximately 3 days or sooner if necessary. When at all possible, affected animals should be housed in a clean and dry area where they can be monitored during the recovery period for signs of improvement or deterioration that may indicate a need for reexamination.

Control————-

Prevention of foot rot is of course, preferable to treatment. Effective preventative measures include minimizing the time cattle can stand in wet contaminated areas, as well as minimizing exposure to clipped weeds, pasture or brush that has stubble high enough to injure the interdigital skin. Footbaths are impractical for most beef operations, although may be possible for small herds. Other preventative measures include the addition of zinc and/or organic iodine to the feed or mineral mixes and vaccination. If cattle are moderately to severely deficient in zinc in the diet, supplemental zinc may reduce the incidence of foot rot. One study supported the use of 5.4 gms per day of zinc methionine in grazing steers. Historically, organic iodide (EDDI) has been added to salt mixes to aid in the prevention of foot rot. Vaccination with a killed F. necroforum bacterin (Fusoguard-Novartis) may reduce clinical signs of infection and should be considered if other control methods fail or a severe outbreak is anticipated. It requires an initial vaccination with a booster dose given 3 weeks later.

Control measures include footbathing of animals with 5% copper sulphate or formalin. Zinc methionine and paraformaldehyde have also been used.

Proprietary vaccines are available but it is, at present, questionable if they are cost effective. Two injections are required one month apart, but the immunity that develops only reduces the incidence of the disease and does not eliminate the risk completely. Vaccinating bulls twice per year is strongly recommended to maintain breeding performance.

The reduction of slurry is also extremely important. Good drainage around drinking and feeding areas is helpful. The isolation of cows (or the use of a protective boot) during the early infectious stages of the disease is strongly recommended. Very early, adequate treatment is essential.

Compiled & shared by-DR. RAJESH KUMAR SINGH, (LIVESTOCK & POULTRY CONSULTANT), JAMSHEDPUR, JHARKHAND,INDIA 9431309542, rajeshsinghvet@gmail.com