Why India’s next Operation Flood should be of non-bovine milk

The demand for the milk of non-bovine (other than cows and buffaloes) animals, such as goats, sheep, camels, donkeys, and yaks, has begun to swell, thanks to the growing awareness of their nutritional and therapeutic virtues. Several commercial ventures, including start-ups and established dairy brands, have begun manufacturing products like milk powder, cheese, yoghurt, ice cream, chocolates, cosmetic products, and various other kinds of specialty items with non-bovine milk. The milk of goats and camels and their products are readily available in major dairy product outlets and online marketing channels. In Europe, donkey farms have come up on the lines of cow-based dairy farms to meet the requirements of baby food manufacturers. This milk is deemed closest to human milk in its composition and digestibility and has been used for ages in many countries as an alternative to mother’s milk. It is now finding a new application in stamina-boosting drinks for sports persons because it is low in cholesterol and fat but high in energy.

Milk, in general, is a food of major global economic importance with recent research suggesting humans have been exploiting animal’s milk as a food resource as far back as the Bronze Age (3,000 BCE). Animal’s milk is an excellent nutritional resource, containing high levels of clean liquid, sugar, fat, B-vitamins and calcium. Humans have adapted behaviourally to milk consumption by developing techniques such as pasteurising and curdling and also biologically by evolving lactase persistence, a genetic adaptation which allows the digestion of lactose in milk. The consumption of milk and milk products varies from country to country, from Finland consuming 180 litres per capita to 50 litres in Japan and China. Liquid milk consumption in the UK is relatively high, measured at 102 litres per capita. Whilst bovine milk is the most predominant of dairy foods in the world, non-bovine (e.g. sheep, goat, donkey, reindeer, and camel) milk is also a key source of nutrition in some parts of the globe.

- Bovine milk is the most popular and economically important type of milk in developed countries, including the India.

- As consumers demand more diverse products and interest in speciality foods grows this leaves a niche for non-bovine milk (from sheep and goats).

- Sheep and goat milk is rich in a broad spectrum of vitamins and minerals and can be suitable for those suffering from a cow’s milk allergy.

Furthermore, non-bovine milk, in particular, goat’s milk, is emerging as an effective ingredient for pro-biotics. Yoghurts from bovine milk tend to be the most common sources for commercial pro-biotic products containing live microorganisms that confer a health benefit to the consumer. Demand for pro-biotics based on non-bovine milk is increasing due to allergies, intolerances and interest in ‘healthier’ food in general. Both goat’s and sheep’s milk have been reported to contain higher levels of health beneficial unsaturated fatty acids than cow’s milk, with goat’s milk containing more zinc, iron and magnesium in addition to better digestibility. In testing, goat’s milk has proven effective in the manufacture of probiotics, maintaining the viability of microorganisms during storage and even enhancing their function. The main barrier preventing more widespread use of goat’s and sheep’s milk is its sensory properties, which for many consumers remain unappealing when compared to bovine milk.

Nutritional composition of non-bovine milk

Small dairy ruminants (sheep and goats) currently produce 3.5% of the world’s milk and are mainly found in sub-tropical-temperate areas of Europe, Asia and Africa. Dairy sheep are most commonly found around the Mediterranean where their dairy products are key components of the human diet. Dairy goats are mostly found in low-income, food-deficit countries of India where their products are an important food source, although, the demand for non-bovine milk (NBM) is now increasing in developed countries. The reasons behind increased demand include a greater ability to detect and accurately diagnose dairy allergies and intolerances as well as the expanding market for ‘healthier’ foods.

Goat’s milk presents an alternative for those who are sensitive or allergic to cow’s milk. Cow’s milk allergy (CMA) is a common disease of childhood, characterised by an abnormal response to the proteins found in cow’s milk. In some cases, goat’s and sheep’s milk may act as a substitute, with research finding between 25 and 40% of patients with CMA are able to tolerate goat’s milk. Of course, this is not true for everyone with CMA as the structure of proteins in ruminant milk are similar regardless of species.

On the whole, goat’s milk contains larger proteins and smaller fat globules when compared to cow’s milk, in addition to more short- and medium-chain fatty acids which are beneficial when making cheese. Sheep’s milk is rich in proteins, minerals (calcium, phosphate and magnesium and fats (mostly medium chain), this richness results in high cheese-making yields. In both goat’s and sheep’s milk, extremely low levels (ranging to trace) of agglutinin make it more digestible when compared to cow’s milk.

When compared to cow’s and goat’s milk, sheep’s milk contains higher levels of protein and fat, with a slightly higher amount of PUFA and CLAs (Table 1). It also offers high amounts of calcium (essential in bone formation/health, nerve function and the immune system), phosphorous (healthy bones & teeth), magnesium (healthy immune system) and vitamin C (essential in all bodily functions), especially compared to cow’s milk, but is also a significant sources of retinol which is extremely low in goat’s milk (Table 1). Retinol is a form of vitamin A that plays a role in good immune function and is critical for normal vision.

When examining the nutritional properties of cow’s milk, it excels in very different areas, for example it provides a good source of carotenoids (antioxidants), folate (used in DNA and cell division), vitamin B12 (broad spectrum and essential for brain function) and iron (carries oxygen in the blood) whilst also offering significantly lower fat content compared to that of sheep and goats.. Cow’s milk also boasts a more acceptable flavour and can be produced in much larger quantities than from small ruminants.

In general, the nutritional composition of goat’s milk tends to sit between cow’s and sheep’s milk. Whilst it contains higher levels of many beneficial minerals than cow’s milk (e.g. magnesium and phosphorous) it does not boast the same level as sheep’s milk (e.g. calcium and zinc) (Table 1). Goat’s milk does offer a good source of potassium (used in fluid balance and muscular movement) but the fatty acid profile is not as ‘healthy’ as that of cow’s or sheep’s milk.

The market for non-bovine milk

The benefits of NBM as a food source are clear, as sheep’s milk provides a superior level and spectrum of nutritional advantages (Table 1). When considering the animal in general, it is easy to see why small ruminants are used in milk production in remote areas with harsh climates– they are well-adapted and thrive on nutritionally poor forage, requiring very low inputs. As such, sheep and goats lend themselves to less developed areas of the globe where their multiple purposes (milk, meat, skin, wool etc.) are a great advantage – contributing to poverty and hunger alleviation. In the western world, there is also a portion of the population that enjoy goat’s/sheep’s milk and its associated produce as a traditional speciality or novelty. In particular, goat’s and sheep’s milk cheeses are value-added and often artisan products which consumers are willing to pay a premium for. Currently, producers are working to move sheep’s and goat’s milk products (as well as goat’s meat) into commercial markets to boost sales and profits, this is evidenced by the adoption of feta and halloumi cheese, for example, in most supermarkets. Nevertheless, further work is necessary to develop our understanding and characterisation of NBM so that it can be successfully processed on a large scale. The move towards commercialisation also highlights the problem of production from small ruminants – as previously mentioned sheep and goats cannot produce the volume of milk that cows do, simply due to their size.

No other country can boast such a diversity of milk sources, and the opportunities they represent, than India. As the West wakes up to their benefits, we need to tap into different animal sources that we have and our rich custom of plant-based milks

In Nitya S Ghotge’s survey, “Livestock and Livelihoods: The Indian Context”, she notes that in Ahmedabad the term ‘shecago milk’ is occasionally used.

This does not, as it may sound, have anything to do with the American city. As the spelling suggests, it refers to “Sheep-Camel-Goat” milk, all mixed together. During summers, when regular cow and buffalo milk production is low, ‘shecago’ milk can be a useful supplement and mixed into the main supply to keep up general milk stocks.

This is a reminder of India’s amazing diversity of milk sources. We tend to think of milk mainly in terms of cow milk, followed by buffalo, but there are also the three ‘shecago’ sources, plus milk from yaks in the Himalayas and mithun (domesticated wild bison) in the Northeast, and even some donkey milk.

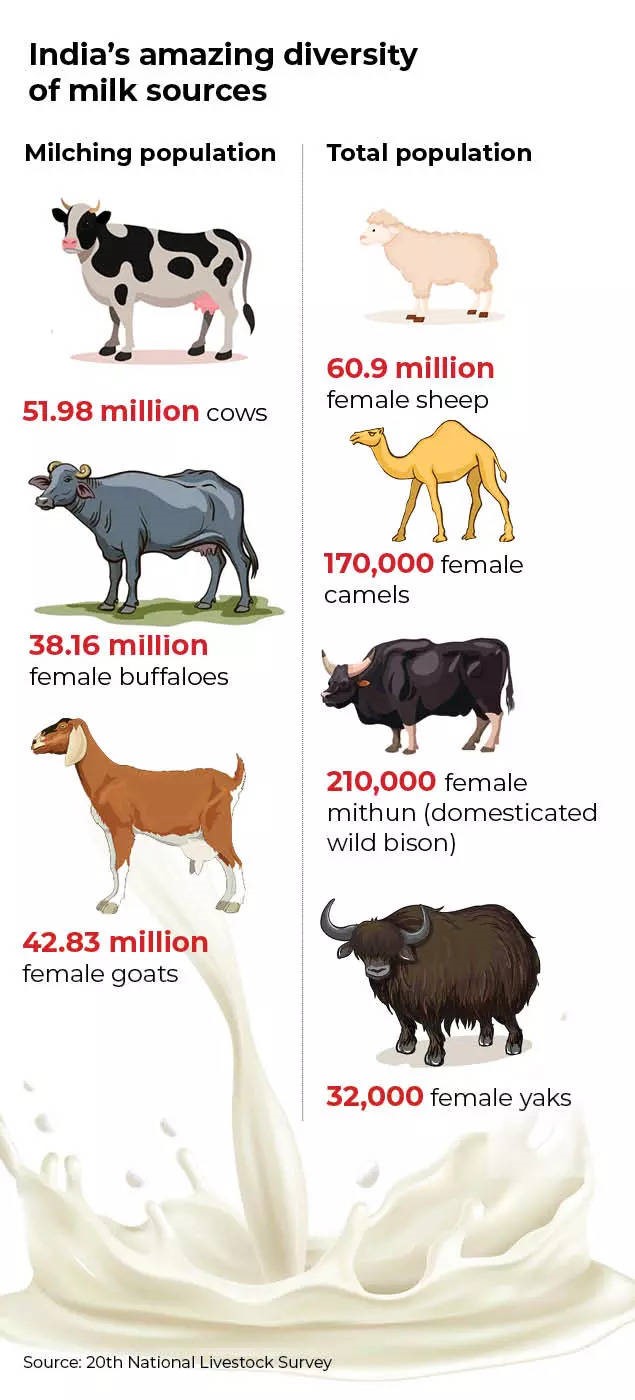

The National Dairy Development Board recorded milk production in 2019-20 of 198.4 million tonnes, and while it does not record the exact sources, some idea of the diversity of sources is evident from the 20th National Livestock Survey, conducted in October 2018, and issued in 2019.

This recorded 51.98 million cows in milk (out of 145.12 million cows in total), 38.16 million female buffaloes in milk (100.57 million female total) and 42.83 female goats in milk (116.78 million female total). Other livestock weren’t differentiated by milk production, but to give a general idea, there were 60.9 million female sheep, 170,000 female camels, 210,000 female mithun and 32,000 female yaks.

And this is just animal sources. Plant-based milks, made by soaking seeds and nuts, and then grinding and straining to create emulsions that are the equivalent of animal milk, are now increasing demand across the world for vegan diets, or by anyone concerned with the environmental costs of livestock farming.

Part of our diet

But several plant-based milks have a long history of consumption in India, paruthi paal , or cottonseed milk from Tamil Nadu, gasagase halu , or poppy seed milk from Karnataka. Above all, there is coconut milk that sustains cooking throughout coastal India.

Coconut milk is used for seafood curries as varied as Kerala’s fish molee and Bengal’s chingri malaikari, in sweets like Goa’s bebinca and south Indian payasam . It is also used for wedding rituals like Ros Kaddunk – a coconut milk bath for couples — at Goan Catholic weddings.

It is a possible sign of how coastal narratives are literally marginalised in India that coconut milk’s importance is neglected, compared to how it’s treated in Southeast Asia. As far back as 1936, the Imperial (now Indian) Council of Agricultural Research was, according to a report in the Times of India dated December 11 that year, considering opening production facilities in Trivandrum for bottled coconut milk.

Yet, even today, the most easily available source of prepared coconut milk is tins imported from Thailand. Only recently have Tetra Pak and dried versions become available from companies like Dabur. Coconut milk is still mostly produced, as it has been for centuries, by intensively grinding, soaking, and squeezing to extract the rich milk.

Soymilk is another plant-based milk, which is seen as a recent entrant into India. Yet, in 1935 Mahatma Gandhi was experimenting with it at his Sevagram ashram. He was encouraged in this by Narhar Bhave, the father of Vinoba Bhave, who was trying to live on a predominantly soybean diet. Gandhi never seems to have been able to produce good quality soymilk on the scale he needed, but he recognised its potential.

Another plant-based milk with real potential in India is cashew. It’s the vegan milk of choice in the West because of its rich, smooth taste, and most commonly used to make vegan cheese. But it is held back by the high cost of cashews, which are mostly imported from India. Cashews must be extracted from their protective casing, a tricky process that is still mostly done by hand in order to get whole kernels.

India controls this part of cashew processing because we have the manpower — or, more accurately, woman power — to do this economically. But cashew milk does not need whole kernels. In places like Goa, vegan cooks are happily using the cheap cashew fragments that are by-products of processing. India is well-placed then to install mechanised processing that extracts cashew specifically for the purpose of making cashew milk, for domestic consumption or export.

No other country can boast such a diversity of milk sources, and the opportunities they represent. And yet, we seem set on ignoring this. As the ‘shecago’ example shows, many of these diverse milks have simply been poured into the general supply, rather than being separately monetised.

Another example, from about a decade back, was when a friend who is interested in cheese-making tried working with a group of goat farmers in Gujarat to create goat milk cheeses of the kind that are much prized in Europe. But the farmers weren’t interested, declaring that it was easier for them just to sell it as general milk.

Even buffalo milk, which the Amul movement was really based on, has been obscured. When Amul first came out with Tetrapak milk it used branding that clearly signalled it came from buffaloes, and in places like Gujarat it still packages and sells this milk separately.

But in general, buffaloes have vanished from Amul’s branding and a senior official there once admitted to me that this was because it was mostly being mixed with cow milk, and consumers tended to prefer to assume they were consuming the latter.

There are some signs that this is changing. An artisanal cheese movement is developing now that is seeking out really good quality milk, and keen to work with different types. Italians use buffalo milk to make cheeses like mozzarella and burrata, and now some have brought their expertise to the country that produces the most buffalo milk, selling under names like Impero. Swiss Happy Cow, a Goa-based cheese maker makes excellent goat milk cheeses whenever they can get enough supply.

Camel milk was once a curiosity — many people must have noticed the sign outside imposing Bikaner House in Delhi advertising it but never stopped to try. It has now acquired a reputation as a health elixir and is sold in both fresh and dried forms.

A variety of the yak cheese called chhurpi that was hard dried for storage, and also to chew like nutritious, edible chewing gum, is now being valued as a high protein source, both for humans and teething puppies. Even donkey milk is, apparently, being sourced for use as a beauty aid.

Plant-based milks face a different challenge. Despite ample evidence of their long use in India, with names that include words like ‘ paal ’, ‘ halu ’ and ‘ dudh ’ which recognise they are a kind of milk, the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) has been waging a campaign to stop them using ‘milk’ in their labelling and marketing. Fortunately, in September 2021, the Delhi high court put a hold on the FSSAI order, allowing five companies selling plant-based milks to continue to use dairy terms.

Rather than a threat, production of both plant-based, and animal milks from multiple sources, should be seen as an opportunity. Co-operative structures, like Amul’s should be encouraged, for goat, camel and other animal milks, and also coconut and cashew farmers, to develop milk as a value-added product.

This would be a suitable way to celebrate, rather than deny, the exceptional diversity of animal and plant milks that have always been part of India’s food traditions.

Potential of Non-Bovine Milk (NBM) in India