CYSTIC ENDOMETRIAL HYPERPLASIA-PYOMETRA COMPLEX IN DOGS

N.K. Bante1, S. Sinha1, R. Mishra2, B. Reddy2, J. Singh3, S. Sinha1, S.K. Maiti1 and M.K. Awasthi2

- Teaching Veterinary Clinical Complex; 2. Deptt. of Gynaecology & Obstetrics, College of Veterinary Science & A.H. 3.Wildlife Health & Forensic Centre, Dau Shri Vasudev Chandrakar Kamdhenu Vishwavidyalaya, Durg, Chhattisgarh

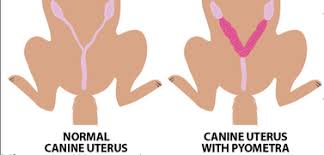

Cystic endometrial hyperplasia-pyometra complex is an acute or chronic post-estrual disorder of adult intact bitches. Several terms such as chronic endometritis, chronic purulent metritis or cystic endometrial hyperplasia complex, have been used in the literature to describe the condition. It is also called pyometritis, pyometra complex, catarrhal endometritis, purulent endometritis, chronic cystic endometritis and chronic purulent endometritis. It is seen in intact bitches and queens of all ages, but is most frequently seen in animals over 3 years of age. This condition most commonly occurs in bitches starting at 3 to 4 years of age. The incidence increases with age and after exposure to several non-pregnant cycles.

Pyometra is a hormonally mediated diestrual disorder caused by bacterial infection within uterus. It results in mild to severe and life threatening bacteremia and toxemia. Predisposing condition is CEH (Cystic Endometrial Hyperplasia) where uterus undergoes a pathological change that leads to sepsis. CEH is caused by an abnormal uterine response to chronic and repeated exposure to progesterone. CEH does not always precede pyometra. Severe life threatening pyometra can occur in absence of CEH.

Theories on pyometra:

The classical theory of the pathogenesis of the spontaneous pyometra disease involves the suppression of immune responses, stimulation of endometrial gland secretion (providing a suitable environment for bacterial growth), functional closure of the cervix (inhibiting drainage of uterine exudates) and, perhaps most importantly, cystic endometrial hyperplasia (all related to the influence of progesterone on the uterus). In this theory. Progesterone-mediated degenerative processes facilitate the bacterial development and invasion of the uterus.

A more recent theory suggests that this may not be so, and that a subtle (subclinical) uterine infection may occur first, providing the stimulus for excessive endometrial hypertrophy and hyperplasia (the so-called trophoblastic reaction based on the observed hyper-reaction of the uterus at implantation). The associated increased glandular secretions would exacerbate the infection leading to further secretion by endometrial glands and luminal epithelial cells progressing to pyometra.

The classical theory is probably the one which best explains the more common pyometra observed in older animals, whereas the new trophoblastic theory is interesting in that it more easily explains the occurrence of unilateral pyometra and pyometra in younger dogs.

Incidence: Renukaradhya (2011) reported that CEH-pyometra is common in nulliparous bitches (69.63%) than multiparous bitches. The incidence was more in dogs aged around 5-9 years (50.95%).

Dow’s Classification of CEH-Pyometra: Dow (1959) described four stages of CEH-pyometra.

- Type I is uncomplicated CEH. Grossly, the endometrium has a cobblestone appearance, with thickening and many cystic irregular elevations, 4-10 mm in diameter covering the endometrial surface.

- Type II is CEH plus diffuse infiltration of plasma cells. No tissue destruction is visible histologically.

- Type III is CEH with overlying acute endometritis. Areas of Endometrial ulceration & hemorrhage may be visible grossly. Reddish brown to yellow green uterine discharge may be present. Myometrial inflammation is also noticed in this type.

- Type IV is CEH with chronic endometritis. If the cervix is open, it allows drainage of intrauterine fluid. The uterine horns will be narrow in diameter. The uterine walls will be grossly thickened. If the cervix is closed, the uterine horns are distended with purulent fluid. Marked atrophy of the endometrium and myometrium are present.

Chitra (2013) investigated the condition and classified the CEH-pyometra into four groups based on histopathological observations as:

- Cystic endometrial hyperplasia without haemorrhage: This type was characterized by endometrial hyperplasia and cystic enlargement of the glands with absence of haemorrhage (60% of the pyometra were under this category).

- Cystic endometrial hyperplasia with haemorrhage: This type was characterized by endometrial hyperplasia and cystic enlargement of the glands with massive haemorrhage and congestion (20.1% fall under this category).

- Cystic endometrial hyperplasia with fibrosis: This type of lesion was characterized by fibrotic changes either in the endometrium or myometrium (11.4%).

- Haemorrhage without cystic endometrial hyperplasia: This type of lesion had hemorrhages into the endometrium and myometrium but revealed no epithelial hyperplasia or cystic enlargement (8.6%).

Pathogenesis of CEH-pyometra complex:

CEH is caused by repeated exposure of the endometrium to progesterone. Estrogen promotes growth, vascularity and edema of the normal endometrium, cervical relaxation and dilatation and migration of polymorphonuclear leukocytes into the uterine lumen. Whereas, progesterone stimulates proliferation and secretory activity of the endometrial glands, maintains functional closure of the cervix and inhibits myometrial contractility.

Estrogens may increase the number of receptors for progesterone in the endometrium, thereby amplifies its effect. The normal down-regulation of estrogen receptor expression in uterine endometrial glands under the influence of rising progesterone may be defective in dogs with CEH. This leads to more prolonged effect of estrogen in the endometrium. This combined with bacterial infection most commonly from the resident bacteria of the vaginal vault results in pyometra. With secondary bacterial infection, especially E. coli, toxemia develops as a result of release of endotoxins that interferes with the absorption of sodium and chloride in the loop of Henle. This reduces the renal medullary hypertonicity, thereby impairing renal collecting tubules’ ability to reabsorb free water. This results in polyuria and a compensatory polydipsia. Renal tubular immune complex injury is another proposed mechanism for polyuria/polydipsia.

Progesterone and infection: The progesterone concentration in anestrous bitches is low (<0.5 ng/ml). During proestrus, the concentration increases to 1 ng/ml and at the onset of estrus, it reaches >2 ng/ml. Its concentration increases throughout estrus and continues through first several weeks of diestrus, followed by a plateau and then a slow return towards basal levels. Return of concentration < 1ng/ml marks the end of diestrus.

During the first 9-12 weeks following ovulation, plasma progesterone levels increases (40ng/ml). It promotes/supports endometrial growth and glandular secretion while suppressing myometrial activity, thereby allowing accumulation of uterine glandular secretion. These secretions provides an excellent media for bacterial growth. Bacterial growth is further enhanced by inhibition of leucocyte response in the progesterone primed uterus.

Exogenous estrogen enhances the stimulatory effects of progesterone on uterus. Supraphysiological concentrations of estrogen resulting from exogenous administration (mismate injection) during estrus/diestrus dramatically increases the risk of development of pyometra.

Bacteria: Even though other bacteria have been identified and isolated, the bacterium usually associated in CEH-pyometra complex is E.coli. It is a Gram negative bacteria containing biologically active lipopolysaccharide in cell membrane. Endotoxin is released as bacteria die and disintegrate.

Two Distinct Pyometra Syndrome:

- The older bitch: This refers to occurrence of pyometra in dogs older than 7 or 8 years age. These old dogs are prone to CEH and subsequently pyometra develops. This is due to age related occurrence from repeated exposure to P4 during normal diestrus.

- The younger bitch: This refers to pyometra occurring in young bitches that are less than 6 years of age. Development of CEH is unlikely in the younger bitch. A strong correlation exists between incidence of pyometra and estrogen administration in young dogs.

Signalment:

- CEH and pyometra are reported to occur most commonly in dogs 8 years or older.

- Disease may occur in younger animals, especially those that had received for pregnancy termination or progesterone for estrus suppression.

- No breed predisposition is reported.

- CEH and pyometra is more common in nulliparous than in multiparous bitches.

Clinical Signs:

- The signs reported by the owner depend upon the patency of the cervix.

- Sanguineous to mucopurulent from the vagina in open cervix pyometra.

- Lethargy, depression, inappetence, polyuria, polydipsia and vomition are other clinical signs.

- Bitch with closed pyometra is usually ill at the time of diagnosis. Depression and anorexia in conjunction with polyuria, vomition or diarrhea can be seen which leads to dehydration, shock, coma and eventually death.

Diagnosis of CEH-pyometra:

- History: Significant events that should be recorded in the history of bitch with suspected CEH- pyometra include whelping history, prior treatment with estrogenic or progestogenic drugs, contraception, pregnancy termination and the length of time elapsed since completion of the most recent estrus. Majority of bitches present with CEH-pyometra within 12 weeks of the onset of previous estrus.

- Clinical signs: Distended abdomen (closed pyometra), polyuria, polydipsia, vomition, dullness, anorexia and serosanguinous to mucopurulent discharge from vagina in open pyometra.

- Abdominal palpation: In cases of open-cervix pyometra, the uterine horns may be detected as thickened, often irregular and slightly turgid structures from 1 to 3 cm in diameter. Care must be taken not to confuse the colon with thickened uterine horns. In cases of closed-cervix pyometra the degree of uterine distension may be greater, and there may be visible abdominal enlargement. In large and obese patients, abdominal palpation may not be possible.

- Laboratory findings: Total leucocyte count is increased (>30,000 cells/mm). Absolute neutrophilia with varying degrees of cellular immaturity develops secondary to infection. A degenerative left shift in neutrophils is observed. Mild normocytic, normochromic, non-regenerative anemia often develops. Mean Packed Cell Volume (PCV) is around 38%, but can range from 21 to 48%.Concomitant hyperproteinemia and hyperglobulinemia results from dehydration. Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN) may be increased if dehydration is present. Urine specific gravity is variable. Early in the disease process, it may be>1.030. Later due to polyuria and polydipsia, urine becomes diluted. Isosthenuria (1.008 to 1.015) or Hyposthenuria (<1.008) is common in bitches with pyometra. Serum creatinine level increases beyond the normal range which may indicate the extent of kidney damage.

- Diagnostic Imaging: Abdominal radiography of affected bitch reveals uterine enlargement. Radiograph does not differentiate the uterine enlargement caused by pyometra from pregnancy until after fetal mineralization occurs (43-54 days after breeding). Uterine enlargement is more easily appreciated in lateral than ventrodorsal radiographic projections.

Ultrasonography is the preferred imaging technique for diagnosis of CEH-pyometra. It is very sensitive for identifying even small accumulations of fluid within the uterine lumen in the early stages of this condition. The intraluminal fluid is best identified in the caudal area of the uterine horns and the uterine body using the bladder as anacoustic window. It also allows determination of the size of the uterus, the thickness of uterine wall and the character of fluid (serous or viscid).

Treatment of CEH-pyometra:

Medical Therapy: Medical therapy for CEH-pyometra may be appropriate in bitches that are of breeding age, vital to breeding program in that kennel, are not systemically ill, with normal BUN and no evidence of endotoxemia, have an open cervix, evidenced by presence of vulvar discharge. If these criteria are not met, medical therapy for CEH-pyometra is discouraged.

- Prostaglandins F2 alpha: The best drug of choice for medical treatment is natural prostaglandins F2 alpha (eg. Inj. Lutalyse). It reduces progesterone concentration, myometrial contractility and promotes expulsion of uterine contents. The protocol for this drug is 0.1 mg/kg s/c once on day 1 followed by 0.2 mg/kg s/c once on 2nd day and later 0.25 mg/kg s/c once daily from 3rd to 7th

Antibiotics are always used during and for 14 days following PGF2 alpha administration. Reevaluate on 7th day after completion of PGF2 alpha and again on 14th day after completion of PGF2 alpha. Re-treatment is recommended at 14 days, if condition persists.

Side effects of PGF2a in the dog include hypersalivation, restlessness, vomition and diarrhea. Side effects occur within 5 minutes and subside within 60 minutes after administration of PGF2 alpha, Severity is dose dependent and decreases with treatment course. Side effects can be reduced in occurrence and severity by walking the bitch for 20 to 40 minutes after administration of PGF2 alpha. Further, vomition can be reduced by administration of anti-emetics like metaclopromide. Inj. Ranitidine can also be given to reduce gastric secretions and vomition.

- Combination of PGF2 alpha and Dopamine agonists: PGF2 alpha at an increasing dose rate of 10-25 µg/kg s/c two to three times daily for 5-7 days and a dopamine agonists either bromocriptine (25 µg/kg 2-3 times daily) or cabergoline (5 µg/kg once daily) has been described. These dopamine agonists inhibit the release of luteotrophic prolactin, thereby causing luteolysis, and are therefore best used in bitches being treated for CEH- pyometra in diestrus.

- Cloprostenol: A prostaglandin analogue has been described for medical treatment of dogs with CEH- pyometra. Dose is 10 µg/kg s/c twice daily for 9-15 days and side effects are similar to that of PGF2

- Antiprogestins: These agents competitively bind with progesterone receptors and decrease intrauterine progesterone concentrations, allowing increased myometrial contractility and cervical relaxation. Mifepristone and aglepristone have been described for treatment of CEH- pyometra in dogs. These drugs can also be used in combination with PGF2 alpha for treatment. The use of aglepristone is also of particular interest in the treatment of closed pyometra, since it induces cervical opening and the subsequent evacuation of purulent discharge with a marked improvement in the animal’s general condition. These findings suggest that surgery is no longer the only treatment for closed pyometra. Moreover, even if surgery has been planned, it is possible to recommend medication as a first-line treatment (aglepristone and rehydration) to improve the general health of the bitch and minimize surgical risk. Dose of Aglepristone (injectable preparation) is 10 mg/kg body weight s/c on day 1, 2 and 7 while oral dose of Mifepristone: (Tablet form) is 5mg/kg body weight BID. Mifepristone can be combined with Misoprostol (PGF2 alpha analogue) at dosage of 5 mg/kg body weight of Mifepristone BID PO for two days followed by 5 µg/kg body weight for another 2 days in case of closed cervix pyometra. Mifepristone causes reduction in progesterone concentration, softening of cervical collagen and increased myometrial contractility. Once the cervix is open, the misoprostol administered helps in complete evacuation of the uterine contents.

Surgical management of CEH-pyometra:

Ovariohysterectomy (OHE) is the treatment of choice for CEH-pyometra in bitches regardless of cervical patency. Surgical technique for OHE in bitches with pyometra is the same as for elective OHE. Caution should be used when handling a distended, friable uterus. Postoperative management following OHE in bitches with pyometra includes supportive care and pain management. Antibiotics should be continued for 7-10 days after OHE.

Further readings:

- Chitra, P. (2013) Studies on haematological, biochemical, hormonal and histopathological parameters in pyometra of bitches. M.V.Sc. Thesis submitted to Karnataka Veterinary, Animal and Fisheries Sciences University, Bidar, India.

- DeClue, A. (2016). Sepsis and the systemic inflammatory response syndrome. In: Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine. Ettinger, S.J., Feldman, E.C. and Cote, E. (EDS). 8th Elsevier, St Louis. pp. 554–560.

- Dow, C. (1959) Experimental reproduction of the cystic hyperplasia-pyometra complex in the bitch. Pathol. Bacteriol., 78: 267-278.

- Fieni, F., Topie, E., Gogny, A. (2014). Medical treatment for pyometra in dogs. Domest. Anim., 49(2): 28-32.

- Jitpean, S., Ambrosen, A., Emanuelson, U. and Hagman, R. (2017). Closed cervix is associated with more severe illness in dogs with pyometra. BMC Vet. Res., 13(1):

- Lopes, C.E., De Carli, S., Riboldi, C.I., De Lorenzo, C., Panziera, W., Driemeier, D. and Siqueira, F.M. (2021). Pet Pyometra: Correlating bacteria pathogenicity to endometrial histological changes. Pathogens, 10: 833

- Mateus, L. and Eilts, B.E. (2009). Cystic endometrial hyperplasia and pyometra. In: Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine. Ettinger, S.J. and Feldman, E.C. (Eds). 7th Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia. pp. 1913-1921.

- Mattoon, J.S. and Nyland, T.G. (2015). Ovaries and uterus. In: Small Animal Diagnostic Ultrasound. Mattoon, J.S. and Nyland, T.G. (Eds). 3rd Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia. pp. 634–654.

- Renukaradhya, G.J. (2011) Studies on treatment of pyometra in bitches with antiprogestins. Thesis submitted to Karnataka Veterinary, Animal and Fisheries Sciences University, Bidar, India. Ph.D Thesis submitted to Karnataka Veterinary, Animal and Fisheries Sciences University, Bidar, India.

- Trasch, K., Wehrend, A., Bostedt, H. (2003). Follow-up examinations of bitches after conservative treatment of pyometra with the antigestagen aglepristone. Vet. Med. A. 50 (7): 375-379.

- Turkki, O.M., Sunesson, K.W., den Hertog, E. and Varjonen, K. (2019). Postoperative complications and antibiotic use in dogs with pyometra: a retrospective review of 140 cases (2019). Acta Vet Scand., 65(1):