Ileus in Dogs : Management of Paralytic Ileus

Ileus is a severe condition in which the intestinal passage is obstructed and as a result digested food cannot be transported past the blockage. Ilneus is not a primary disease, rather a result of other diseases or conditions affecting the intestine. Ileus is a dangerous and acute condition and many dogs may lose weight when they’re suffering from this disease.Paralytic ileus is a state of functional obstruction of intestines or failure of peristalsis. The paralysis does not need to complete to cause ileus, but the intestinal muscles became inactive and it prevents passage of food. There will be loss of intestinal tone and motility. The etiological factors include acid base imbalances, electrolyte imbalances such as hypokalemia, enteritis, intestinal obstruction etc.

Paralytic ileus occurs when the muscle contractions that move food through your intestines are temporarily paralyzed. It’s a functional problem of the muscles and nerves that mimics an intestinal obstruction even when nothing is obstructing them. Food becomes trapped in the intestines, leading to constipation, bloating and gas.

Paralytic ileus occurs in the intestines, the long, tube-like passageway where food is broken down and absorbed before the waste is pushed out as poop. The intestines process your food along this journey through a series of wave-like movements called peristalsis. Paralytic ileus is the paralysis of these movements. It means that the muscles or nerve signals that trigger peristalsis have stopped working, and the food in your intestines isn’t moving. Accumulating stagnant food, gas and fluids in your intestines may cause you symptoms of bloating and abdominal distension, constipation and nausea. This is an acute condition, which means it’s temporary and reversible, as long as the underlying cause has been addressed.

Gastrointestinal symptoms, particularly paralytic ileus, are not only found in primary gastrointestinal tract diseases, but also as a manifestation of other systemic ailments. In the field of internal medicine, in addition to peritonitis, many conditions could cause cessation of smooth muscle motor activity in the small intestines and colon, such as sepsis, as a side effect of certain medications, hormonal imbalance, electrolyte imbalance, and bowel ischemia.Paralytic ileus is a clinical syndrome due to acute and transient disturbance of the transportation of the content of intestinal lumen due to cessation of smooth muscle motor activity in the small intestines and colon, with the potential to return to normal. This differs from physical bowel obstruction (obstructive ileus) caused by a physical/anatomic obstruction in the lumen of the small intestines or colon, which has a clear, simple, and comprehensible pathogenesis, and usually requires surgical intervention. Paralytic ileus usually does not have a clear mechanism, is complex, and is not clearly understood. Several factors, such as neurogenic, myogenic, and humoral factors, are suspected to be involved in the pathophysiology of paralytic ileus.Compared to obstructive ileus, paralytic ileus is more commonly encountered by clinicians. However, we still do not have the statistical incidence data on paralytic ileus, possibly because it is considered as a transient gastrointestinal syndrome with satisfactory prognosis. Up to now, the management of paralytic ileus is aimed at the causative/ accompanying illness. From this literature review, the author hopes that the management of paralytic ileus could be further improved in the future.

How does paralytic ileus occur?

Different kinds of conditions can inhibit your motility — your ability to process food through the digestive system. Paralytic ileus is a functional problem rather than a mechanical one. There’s nothing physically blocking the passage of food in your intestines. The intestines just aren’t doing their job. Sometimes the entire digestive tract is affected, and sometimes ileus is localized in a particular bowel loop near the site of an injury or inflammation. Ileus is usually a temporary reaction of your body to trauma, such as surgery or infection. However, chemical factors, including medications, metabolic disturbances and electrolyte imbalances can also be at fault.

SYMPTOMS AND CAUSES

What are the symptoms of paralytic ileus?

Symptoms may include:

- Abdominal bloating.

- Abdominal distension.

- Gas.

- Constipation.

- Nausea and vomiting.

- Dehydration.

If any of these symptoms are severe, you should treat them as an emergency.

What causes paralytic ileus?

Different kinds of conditions can cause temporary ileus, including:

Surgery

Surgery is the most common cause of paralytic ileus. Surgeons expect and plan for it following abdominal operations. But other surgeries can also trigger it.

Inflammation

Inflammation of the abdominal cavity interrupts intestinal function. Inflammation may be caused by local irritation or toxic infection, such as:

- Appendicitis.

- Pancreatitis.

- Peritonitis.

- Gastroenteritis.

- Cholecystitis.

- Diverticulitis.

- Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis.

- Inflammatory bowel diseases.

- Botulism.

- Sepsis.

PATHOGENESIS/PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF IILEUS IN DOGS

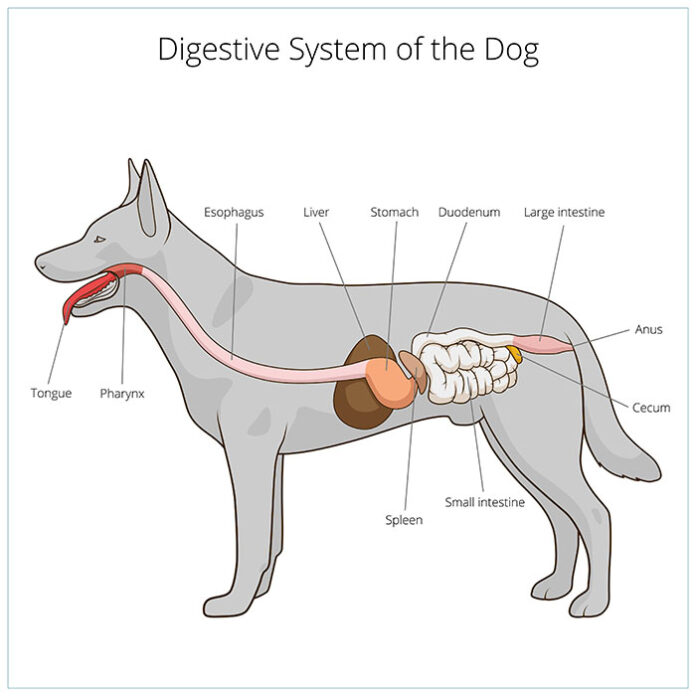

The main function of the small intestines and the colon is to supply water, electrolyte, and nutrients to the body. Approximately 85% of chyme, consisting of 8 liters of fluid (1.5 liters of swallowed fluid and 6.5 liters of fluid from various digestive secretions), nutrients, vitamins, and minerals, is absorbed in the small intestines, while the remaining chyme, mainly consisting of fluid and electrolyte, is absorbed in the colon.3, 9 To be able to do so, food must be digested and moved along the lumen of the small intestines and the colon at an appropriate speed, to allow for digestion and absorption.

MOTILITY OF THE SMALL INTESTINES AND THE COLON

As chyme enters the intestines from the gaster, the proximal portion of the walls of the small intestines is stretched, which causes local concentric contraction at specific intervals along the intestines. This segmental contraction repeatedly divides chyme each minute, causing progressive mixing of solid food particles and the secretions of the small intestines. Simultaneously, there is also a peristaltic wave that pushes the chyme towards the anus with a speed of 0.5-2 cm/second. This peristaltic movement could arise from any part of the small intestines, far more rapidly at the duodenum compared to at the terminal ileum. Thus, under normal conditions, 3-5 hours is required for chyme to reach the ileocaecal sphincter from the pylorus. Concentric contraction also takes place in the colon, while at the same time; there is contraction of the three collections of longitudinal colon muscles on 3 longitudinal bands known as the teniae coli. This collective contraction causes the stimulated portion of the colon to bulge like a sac, so called haustration. This haustral contraction occurs every hour and lasts for 30 seconds, causing the content of the content to blend. This slow yet persistent haustral contraction is the main force that pushes the chyme from the ileocaecal sphincter to the transverse colon, in the caecum and ascending colon. From the transverse colon to the sigmoid, a peristaltic-like motion of the bowel, known as mass movement, replace the haustral contraction as the thrust force for bowel content. As it moves through the colon toward the anus, the fluid chyme gradually becomes more solid, until only approximately 80-200 cc of fluid remains in the feces.

REGULATION OF SMOOTH MUSCLE AND COLON MOTILITY

An intramural nerve plexus resides within the walls of the small intestines and colon, known as the enteric nervous system, made up of two layers of neurons and relevant connector nerve fibers. The myenteric (Auerbach) plexus is located in the outer part between the longitudinal and circular layer, while the submucosal plexus (Meissner) is located in the submucosa. The myenteric plexus particularly controls motility, while the submucosal plexus particularly controls secretion, absorption, and intestinal blood flow This enteric nervous system is able to maintain independent function (by reflex), and is thus called the mini gut brain, even though its mechanism is still influenced and modified by the central nervous system through the parasympathetic and sympathetic components of the autonomous nervous system. Stimulation of the parasympathetic component increases intestinal and colon motility, while stimulation of the sympathetic component inhibits intestinal motility. This can be seen from how several important reflexes mediated by the sympathetic component that cause inhibition of the motility of the small intestines and colon resemble one another, such as the intestino-intestinal reflex, which occurs if an intestinal portion is overly distended or its mucosa excessively irritated, inhibiting the motility of the other parts of the bowel; the peritoneo-intstinal reflex that occurs if there is iritation of the peritoneum; the reno-intestinal and vesicointestinal reflex that occurs if the kidneys or bladder is irritated; and the somato-intestinal reflex that occurs if the abdominal skin is overly irritated.The parasympasympathetic component is located in the nucleus of the cranial division of the vagal nerve and the sacral segment of the medulla spinalis. The vagal nerve especially innervates the esophagus, gaster, and the pancreas, and only contributes little in the small intestines to the proximal portion of the colon, while the sacral divison goes through the cranial nerves to innervate the distal portion of the colon (the sigmoid colon, the rectum, and anus), which plays an important role in the defecation reflex. The sympathetic component is located on the thoraco-lumbal segment of the medulla spinalis, and the preganglionic nerve fibers leave the medulla spinalis towards the distant prevertebral ganglia, such as the celiac and mesenteric ganglia. Unlike the parasympathetic component, which innervates the oral and anal portions, the sympathetic component innervates the whole intestine and colon via its postganglionic nerve fibers. When stimulated, end fibers of the parasympathetic system releases acetylcholine, which increases the motility of the intestines and colon. On the other hand, stimulation on the sympathetic peripheral nerve fibers causes the release of noradrenaline, which inhibits peristaltic movement of the intestines and colon.Increased plasma cathecolamine due to postoperative stress is suspected to be closely related to postoperative paralytic ileus. In laboratory animals, adrenalectomy does not improve post-operative paralytic ileus, while splanchnicectomy returns a portion of intestinal motility. This is important in demonstrating the role of the sympathetic component in the inhibition of the motility of the intestines and colon, while the role of adrenaline in post-perative paralytic ileus remains unclear. The role of hormonal factors in the motility of the small intestines is still unclear, and is still being studied by many experts. Several hormones that are supposedly secreted during the process of digestion, such as gastrine, cholecystokinine, motiline, P substance, and insulin, increase intestinal peristalsis; while secretine, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP), and glucagon inhibit the intestinal peristalsis. Various clinical conditions in the field of internal medicine, such as peritonitis and retroperitoneal inflammation, hormonal and electrolyte imbalance, druginduced conditions, blood-borne toxins, as well as disturbances in oxygen supply, are able to inhibit intestinal and colon motility (thus causing paralytic ileus). Several myogenic, neurogenic, and humoral factors are suspected to play independent or collective roles in the basic mechanism of the development of paralytic ileus under these conditions

Medications

Medications known to slow motility include:

- Anticholinergics.

- Opioids.

- Tricyclic antidepressants.

- Phenothiazines.

Electrolyte disturbances

Electrolyte imbalances that may be involved include:

- Hypokalemia.

- Hypercalcemia.

- Hypomagnesemia.

- Hypophosphatemia.

Other

Other conditions associated with paralytic ileus include:

- Renal failure.

- Respiratory failure.

- Pneumonia.

- Spinal cord injuries.

- Mesenteric artery ischemia.

- Diabetes-related ketoacidosis.

- Hypothyroidism.

- Heart attack.

- Thyroid diseases.

DIAGNOSIS AND TESTS

How is paralytic ileus diagnosed?

Your medical history and a physical examination are often enough to diagnose ileus. An X-ray or abdominal ultrasound can confirm the condition by showing swollen and dilated segments of bowel without any mechanical blockage to explain them. Your healthcare provider may also use imaging tests to look for the cause if it isn’t already known. They may take a blood test to check your electrolyte and mineral levels.

MANAGEMENT AND TREATMENT

In essence, management of paralytic ileus directly aims to address the etiology, without the need of surgical management.2, 3, 16 Up to now, there is no drug/ pharmacotherapy that has been proven to be beneficial to restore intestinal or colon motility in patients with paralytic ileus.

Supportive Therapy

Supportive therapy for paralytic ileus consists of:

• General care

• Correction of fluid, electrolyte, and acid-base imbalance

• Abdominal decompression

• Total parenteral nutrition

General Care

- Information and education on the patient’s illness and management to the patient and family is very important, since therapeutic success is very much determined by the patient’s cooperation, such as fasting, the need to insert a nasogastric tube, further investigation, and drugs that need purchasing.

• Bed rest.

• Fasting.

• Monitor general condition and vital signs (consciousness, blood pressure, pulse rate, temperature, and respiratory rate) intermittently every 6-8 hours for the initial 24-48 hours.

• Insert an IV line and administer crystalloids (0.9% NaCl or lactic ringer fluid) for emergency. Adjust the volume and rate of administration according to the patient’s condition.

• Conduct the following laboratory evaluations: complete peripheral blood check, ureum and creatinine, blood sugar, serum electrolyte, blood gas analysis.

• Insert a urinary catheter to determine 24 hour urine output.

• Monitor using ECG to identify hypokalemia.

• Evaluate laboratory findings (complete peripheral blood check, ureum and creatinine, blood sugar, serum electrolyte, blood gas analysis) every 6-8 hours for the initial 24-48 hours.

How is paralytic ileus treated?

If the cause is unknown, that will be addressed first. You may have an infection or disease that needs to be treated. If ileus occurs as a natural side effect of surgery, your healthcare team will already have a treatment plan in place. Treatment includes:

- Bowel rest. You’ll avoid eating by mouth until your bowel function has returned.

- Parenteral nutrition. You may need to have your fluids, electrolytes, and nutrients replaced through an IV.

- Prokinetics. Medications to promote peristalsis may help reboot your bowel function if it doesn’t recover soon enough on its own.

- Nasogastric tube. In severe cases, a thin tube may be passed into your stomach through your nose to drain air and fluid.

Treatment

As ileus is a result of other diseases or conditions, treating the underlying cause is of utmost importance. Additionally, fluid therapy and drugs to enhance intestinal motility are also given to stimulate intestinal movements. During treatment, the veterinarian will use a stethoscope to listen to the stomach of the dog in order to examine the development of inner sounds and motility. If the stomach is tight and hard and no movement can be heard, ultrasound will be needed. Ultrasound and x-ray examination can reveal grossly distended bowel slings and possibly even the site of the blockage. In some cases of ileus, surgery is necessary to remove the blockage.

The animal is successfully treated with fluids (Dextrose Normal Saline @ 10 ml/kg body weight and Ringer lactate @ 20 ml/kg body weight intravenously), antibiotics (Sulphatrimethoprim @ 15 mg/kg body weight and Metronidazole @ 20 mg/kg body weight intravenously), antiemetics (Metachlopramide @ 0.3mg/kg body weight subcutaneously) and prokinetics (Erythromycin @ 1 mg/kg body weight orally ) for a period of two weeks. The owner is advised to include fibres in dog’s diet and also advised to maintain it under less carbohydrate diet. Use of prokinetics along with correction of electrolyte imbalances helps in the drastic recovery of this condition.

Paralytic ileus is never a primary disorder, but instead is a clinical syndrome due to acute and temporary loss of smooth muscle motor activity (motility) in the small intestines or colon.

• In the field of internal medicine, paralytic ileus is most commonly caused by peritonitis, which is most often caused by acute pancreatitis.

• Several other cases that could cause paralytic ileus include electrolyte imbalance, drug use, sepsis, and all body infection/inflammatory processes.

• The clinical diagnosis of paralytic ileus is made based on characteristic clinical findings as follows: nausea, vomiting, gassiness (distention), meteorismus, diminished bowel sounds. • Identification of the underlying disease is the key to success in the management of paralytic ileus.

• To identify the etiology of paralytic ileus, several diagnostic investigative methods must be performed, such as: laboratory evaluation, ECG, and 3 position radiological examinations. Abdominal ultrasound or imaging may be performed if necessary.

• In managing paralytic ileus, the basic treatment is aimed at the underlying disease of paralytic ileus, and does not require surgical procedures. With suportive therapy and management of the underlying/accompanying disease, paralytic ileus will spontaneously remit.

Compiled & Shared by- Team, LITD (Livestock Institute of Training & Development)

Image-Courtesy-Google

Reference-On Request.

Disclaimer: The information contained in this article of Pashudhan Praharee is not intended nor implied to be a substitute for professional Veterinary action which is provided by your vet. You assume full responsibility for how you choose to use this information. For any emergency situation related to a Pet’s health, please consult your Regd. Veterinarian or nearest veterinary clinic.