Birds Status in “State of India’s Birds (SoIB)” is Indicative of Deteriorating Health of Habitats in India

State of India’s Birds 2023 Report

Habitat and food loss, changing ecosystems see 60% of India’s bird population decline

The declining trajectory of bird populations in India follows global trends, where 48% of birds have declined.

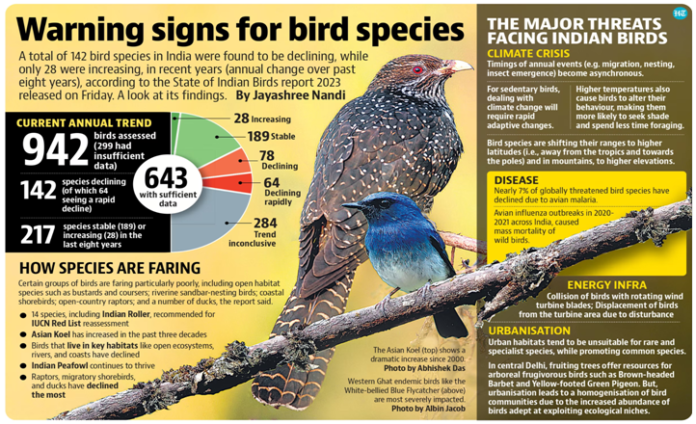

A majority of bird species in India are on the decline – an alarming indication of biodiversity loss and anthropogenic pressures on the environment, a new report assessing bird diversity and population stability in the country has found.

Birds perform a number of important ecosystem services, aiding in seed dispersal and pollination, as well as acting as predators and scavengers. But around 60% of birds assessed in the report have declined over the long term of 30 years, which conservationists have termed a matter of deep concern. Around 40% were found to be declining currently, over the last eight years.

“It’s a two way link. The number of declines could be because of declining ecosystem functioning, or resource availability, or habitat decline itself. But one can also imagine consequences in the other direction. The decline in raptors, for example, could result in changes in populations of rodent communities, which may see a boom,” said Ashwin Viswanathan, Research Associate at the Nature Conservation Foundation, one of the organisations that contributed to the assessment. “A lot of this is speculation. We need to find out how ecosystems are adapting to changing bird numbers,” he added.

The findings were captured in the State of India’s Birds 2023 report, which was released August 25 by a consortium of 13 government and non-profit conservation organizations, and based on 30 million bird sightings. The report identifies 178 birds of high conservation priority which need urgent action plans for their conservation and deeper research to understand the factors leading to their decline. Some of these species include the sarus crane, the Indian courser, the Andaman serpent eagle, and the Nilgiri laughingthrush.

Habitat “specialists” are especially vulnerable, while “generalists”, or birds that have adapted to a variety of landscapes, have been stable in comparison. Some species, like the ashy prinia, rock pigeon, Asian koel, and Indian peafowl “have increased dramatically,” over the years the report finds.

Overall, however, the results are grim and call for a re-classification of 14 species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, or IUCN, to its Red List of threatened species.

Open habitats

The report released last week is the second edition of the State of India’s Birds report, the first of which was released in 2020. The latest report assesses 942 bird species, up from 867 in 2020, and was based on 30 million sightings recorded on the eBird portal by 30,000 citizen birdwatchers. Such citizen science “which may be less or more coordinated, is the only way in which information can be generated for biodiversity assessments at the required scale,” the report says.

“We were surprised to see that, even with a more robust statistical analysis, more data, and more observations than last time, bird populations are declining. This indicates its a more serious problem that we previously realised,” said Rajah Jayapal, a senior scientist with the Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History, which also contributed to the report.

The declining trajectory of bird populations in India follows global trends, where 48% of birds have declined, according to the 2022 State of World’s Birds report. India hosts around 1,350 of the world’s bird species, of which 78 are found only within India.

Birds inhabit all kinds of ecosystems, from coasts and wetlands to high altitudes and tropical rainforests. But birds that occupy open natural ecosystems, particularly grasslands and semi-arid landscapes, are especially vulnerable, with such species declining by 50%, the report says.

A well known example is the great Indian bustard, which is on the brink of extinction because of land use changes and habitat loss. But there are other species that are seeing steep declines too. “Of particular note is great grey shrike, because it has suffered a particularly worrisome long-term decline of more than 80%. This species and other grassland specialists like chestnut-bellied sandgrouse have done better in regions rich in ONEs [open natural ecosystems] compared to the country as a whole, indicating the importance of conserving ONEs,” the report says.

Birds that live in wetlands as well as in wooded areas, such as forests and plantations, have also declined more than generalist species, “indicating a need to conserve natural forest habitats so that they provide habitat to specialists.”

Birds feed on a variety of sources, such as meat (vultures and other raptors), fruits and nectar (barbets and sunbirds), seeds (sparrows and doves), and invertebrates (warblers and flycatchers). Bird populations could also be influenced by limited or contaminated food resources.

“In India, birds that feed on vertebrates and carrion have declined the most, suggesting that this food resource either contains harmful pollutants or is declining in availability, or both. Strong evidence from other countries shows that agrochemicals lower survival rates in some raptors,” the report says, adding, “We find that birds that feed on invertebrates (including insects) are declining rapidly. This needs to be taken together with recent findings that insect populations worldwide have reduced, and that pesticides are thought to be a main contributor to massive declines in European insectivorous birds.”

Over 40% of the world’s insect population has been on the decline and is likely to go extinct in the coming years. Scientists in India suspect similar trends are playing out here, but data is limited.

Fruit and nectar feeding birds are doing well, “maybe because these resources are readily available even in heavy-modified rural and urban landscapes,” the study says.

The report also notes the widespread decline of both resident and migratory ducks, but says there is little understanding of why this otherwise flocking species is reducing in number. “One of the main recommendations is to support research as much as possible, because the data leaves us with so many unanswered questions. We know certain birds and groups of birds are declining, and we now have information to focus research into why,” said Viswanathan.

Threats and recommendations

Even though India has Protected Areas and laws like the Wildlife Protection Act, which awards special protection for certain species, these measures are not sufficient to stop the declining populations of birds in India, whose ranges span from hundreds to thousands of kilometers.

The report locates declining bird populations within eight broad threats, such as environmental pollutants, forest degradation, urbanisation, avian disease, illegal hunting and trade and climate change. The spread of monocultures through commercial plantations or afforestation programmes have reduced biodiversity. “Plantations lack vertical and horizontal vegetation complexity because they maintain even-aged stands of a single tree species for ease of harvest. This usually leads to loss of large-sized trees and reduction in canopy shade and shrubbery,” says the report. The result is fewer bird species occupying these areas compared to rainforest habitats.

Another threat is the expansion of renewable energy infrastructure, such as wind mills. Rotating wind turbines can result in fatal collisions, displacement, or barriers to migration for birds. According to the report, 60 species from 33 families of birds are affected by collisions and electrocution at power lines in India.

“Open habitats are the ones which are immediately available for infrastructure, developmental, and renewable energy projects,” said Jayapal. The report comes at a time when India is rapidly expanding renewable energy and changing its forest policies to accommodate more plantations, while granting more exceptions for the diversion of virgin forests.

“In the face of diverse developmental pressures, maintaining the size and integrity of natural habitats is crucial. Beyond this, where habitats have degraded over time, restoration efforts will be vital: not planting trees in monocultures, but rather ecological restoration of multiple habitats including non- forest habitats like grasslands,” says the report, adding, “One particular challenge will be to mitigate the considerable negative effects of even small-scale infrastructure such as wind energy, often thought of as ‘green energy’.”

Some of the recommendations made by the report include conducting “targeted, systematic, periodic monitoring of bird populations, using consistent methods, over long periods of time. Moreover, monitoring changes in other factors such as disturbance, climate, and land-use is also crucial to building a deeper understanding.”

In 2020, the Indian government announced a 10-year Visionary Protection Plan for the conservation of avian diversity, ecosystems, habitats and landscapes. The Plan outlined steps to be taken in the near, middle, and long term to effectively monitor and raise awareness about bird conservation. The Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History is one of the focal institutes supporting the Visionary Protection Plan.

According to Jayapal, 17 states and union territories have initiated work on their own Visionary Protection Plan, while five – Uttarakhand, Delhi,

Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, and Meghalaya – have completed the process. “By 2030, we expect states to pay more attention to bird conservation issues and work to mitigate priority areas,” he said.

Says Viswanathan, “The amended Wildlife Protection Act took into consideration some of the findings from the SoIB 2020 report, and so we’re hopeful that some policy interventions will follow this one. We’re hopeful that a simple intervention, like recognising open landscapes as open, and not allowing plantation and afforestation activities there will be done.”

Why in News?

Recently, the State of India’s Birds (SoIB) 2023 was released, which highlighted that despite thriving a few bird species, there is a substantial decline in numerous bird species.

- the SoIB 2023is a first-of-its-kind collaborative effort of 13 government and non-government organisations, including the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS), Wildlife Institute of India (WII), and Zoological Survey of India (ZSI), Wildlife Trust of India (WTI), Worldwide Fund for Nature–India (WWF–India) among others, which evaluates the overall conservation status of the most regularly occurring bird species in India.

What are the Methodologies Used in the Report?

- This report is based on data collected from approximately 30,000 birdwatchers.

- The report relies on three primary indices to assess bird populations,

- Long-term trend (change over 30 years)

- Current annual trend (change over the past seven years)

- Distribution range size within India

- Among the 942 bird species assessed, the report indicates that many could not have theirlong-term or current trends accurately established.

What are the Key Highlights of the Report?

- Status:

- For the 338 species with identified long-term trends, 60% have experienced declines, 29% are stable, and 11% have shown increases.

- Among the 359 species with determined current annual trends, 39% are declining, 18% are rapidly declining, 53% are stable, and 8% are increasing.

- Positive Trends: Increasing Bird Species:

- Despite the general decline, there are some positive trends among certain bird species.

- The Indian Peafowl,for instance, the national bird of India, is showing a remarkable increase in both abundance and distribution.

- This species has expanded its range into new habitats, including high-altitude Himalayan regions and rainforests in theWestern Ghats.

- TheAsian Koel, House Crow, Rock Pigeon, and Alexandrine Parakeet are also highlighted as species that have demonstrated a notable increase in abundance since the year 2000.

- The Indian Peafowl,for instance, the national bird of India, is showing a remarkable increase in both abundance and distribution.

- Specialist Birds:

- Bird species that are “specialists’’ – restricted to narrow habitatslike wetlands, rainforests, and grasslands, as opposed to species that can inhabit a wide range of habitats such as plantations and agricultural fields – are rapidly declining.

- The“generalist’’ birds that can live in multiple habitat types are doing well as a group.

- “Specialists, however, are more threatened than generalists.

- Grassland specialists have declined by more than 50%.

- Birds that are woodland specialists (forests or plantations) have also declined more than generalists, indicating a need to conserve natural forest habitats so that they provide habitat to specialists.

- Migrant and Resident Birds:

- Migratory Birds, especially long-distance migrants from Eurasia and the Arctic, have experiencedsignificant declines by more than 50% – followed by short-distance migrants.

- Shorebirds that breed in the Arctic have been particularly affected, declining by close to 80%.

- By contrast, resident species as a group have remained much more stable..

- Diet and Decline Patterns:

- Dietary requirements of birds have also shown up in abundance trends. Birds that feed on vertebrates andcarrion have declined the most.

- Vultures were nearly driven to extinction by consuming carcasses contaminated with diclofenac.

- White-rumped Vultures, Indian Vultures, and Red-headed Vultures have suffered the maximumlong-term declines (98%, 95%, and 91%, respectively).

- Dietary requirements of birds have also shown up in abundance trends. Birds that feed on vertebrates andcarrion have declined the most.

- Endemic and Waterbird Declines:

- Endemic species, unique to the Western Ghatsand Sri Lanka biodiversity hotspot, have experienced rapid declines.

- Of India’s 232 endemic species, many are inhabitants of rainforests, and their decline raises concernsabout habitat preservation.

- Ducks, both resident and migratory, are declining, with certain species like the Baer’s Pochard, Common Pochard, and Andaman Teal being particularly vulnerable.

- Riverine sandbar-nestingbirds are also declining due to multiple pressures on rivers.

- Endemic species, unique to the Western Ghatsand Sri Lanka biodiversity hotspot, have experienced rapid declines.

- Major Threats:

- The report highlighted several major threats – including Forest Degradation, urbanization, and energy infrastructure– that bird species face across the country.

- Environmental pollutantsincluding veterinary drugs such as nimesulide still threaten vulture populations in India.

- Impacts of Climate Change(such as on migratory species), avian disease, and illegal hunting and trade are also among the major threats.

- Other Species:

- Sarus Crane has rapidly declinedover the long term and continues to do so.

- Of the 11 species of woodpeckers for which clear long-term trends could be obtained,seven appear stable, two are declining, and two are in rapid decline.

- The Yellow-crowned Woodpecker,inhabiting widespread thorn and scrub forests, has declined by more than 70% in the past three decades.

- While half of all bustards worldwide are threatened, the three species that breed in India –the Great Indian Bustard, the Lesser Florican, and the Bengal Florican – have been found to be most vulnerable.

- Despite the general decline, there are some positive trends among certain bird species.

What are the Recommendations?

- There is a need to conserve specific groups of birds.For instance, the report found that grassland specialists have declined by more than 50% – indicating the importance of protecting and maintaining grassland ecosystems.

- Systematic monitoring of bird populations over long periods of time is critical to understanding small-scale changesin bird populations.

- It is becoming clearer the need for more research tounderstand the reasons behind the declines or increases.

- The report’s findings emphasize the importance of habitat preservation, addressing pollution, and understanding the dietary requirements of birdsin order to reverse the decline of bird populations and ensure a healthier ecosystem.

What Can be done to Ensure the Viable Population of the Birds in the Ecosystem?

- Habitat Conservation and Restoration:

- Protect and preserve natural habitats, such as forests, wetlands, grasslands, and coastal areas, that are essential for birds’ nesting, feeding, and breeding.

- Restore degraded habitats by planting native vegetation and removing invasive speciesthat can threaten bird populations.

- Protected Areas and Reserves:

- Establish and manage protected areas and wildlife reserves where birds can thrive without human disturbances.

- Implement regulations and guidelines to prevent habitat destruction and disturbances in these areas.

- Reducing Pollution:

- Control pollution sources, including air and water pollution, that can harm bird populations directly or through the contamination of their food sources.

- Promote sustainable practices to minimize pollution in urban and industrial areas.

- Mitigating Climate Change:

- Addressclimate change by reducing greenhouse gas emissions and promoting sustainable energy sources.

- Support habitat corridorsthat allow birds to move and adapt to changing climatic conditions.

- Limiting Human Disturbances:

- Educate the public about the importance of minimizing disturbancesto nesting and feeding sites, particularly during breeding seasons.

- Establish buffer zones around sensitive bird habitats to reduce human interference.

What Measures Have Been Taken to Safeguard Different Bird Species?

- National Action Plan for the Conservation of Migratory Birds (2018-2023)

- Transboundary protected areas for conservation of species likeTigers, Asian elephants, Snow Leopard, the Asiatic Lion, the one-horned rhinoceros, and the Great Indian Bustard.

- Wildlife Protection Act, 1972

- India has taken several steps to conserve vultureslike imposing a ban on the veterinary use of diclofenac, establishment of Vulture breeding centres, etc.

STATE OF INDIA’S BIRDS

https://stateofindiasbirds.in/wp-content/uploads/SoIB-2023_report.pdf

This article was first published on Mongabay.