STRATEGIES TO CONTROL TRANS-BOUNDRY DISEASES OF LIVESTOCK IN INDIA

DR TAPAN SAHU, CHIEF ANIMAL QUARANTINE OFFICER, BENGALURU, GOVT. OF INDIA

Reference- FAO

The impact of Transboundary Animal Diseases (TADs) like FMD, PPR and CSF often transcends national boundaries, and can be the cause of national emergencies.

With technological advances, livestock production has gained an integral position in the agrarian component of the national economy. Livestock farming is one of the important sources of livelihood to rural farmers in India, particularly landless farmers. Increasing contribution of livestock to socioeconomic development and poverty alleviation are well recognized. A healthy livestock is pride of any country. However, rapid trend of globalization has brought upon challenges in maintaining healthy herds of livestock. The emerging infections of foreign origin could spread across national geographical borders and cause havoc. Consequently, there will be an emergence and spread of new disease in the region which was once free from the disease. In this article, we summarize the major diseases of livestock that are trans-boundary in nature, and review the challenges and essential management strategies in controlling the trans-boundary diseases.

INTRODUCTION:

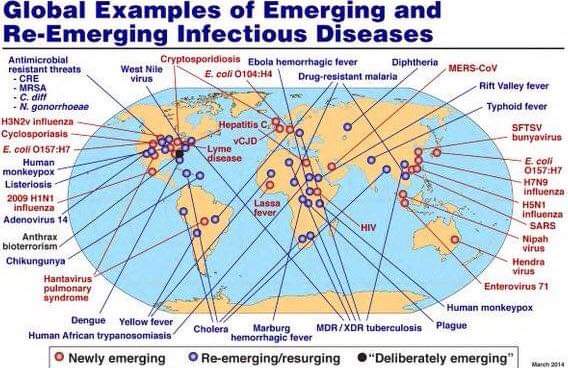

Livestock constitutes an important component of our agricultural system. Livestock provides for livelihood, regular income and women empowerment in rural India. It is unimaginable to have a human society without a healthy population of livestock. Livestock not only provide food security but also improve the quality of human life and make a significant contribution to national economy. Several thousands of small and marginal farmers in the country depend solely on agricultural farming and livestock husbandry. The existence of infectious diseases affecting farm animals has been historically recorded for over hundreds of years. However, factors associated with modernization of human societies such as changes in agro-ecological conditions and global marketing, have led to increased incidences of animal diseases. This is mainly due to spread of disease causing pathogens across borders. With increasing movement of human population, livestock and livestock products, fish and fish products, and plants and plant products within and across countries, together with climate changes, threat from transboundary diseases is intensifying. Transboundary diseases are highly contagious and have the potential for rapid spread, irrespective of national borders, causing serious socioeconomic consequences (Otte et al., 2004). Traditionally, trade, traffic and travel have been instruments of disease spread. Now, changing climate across the globe is adding to the misery. Climate change is creating new ecological platform for the entry and establishment of pests and diseases from one geographical region to another (FAO, 2008). Several new transboundary diseases emerge, and old diseases reemerge, exhibiting increased chances for unexpected spread to new regions, often over great distances. Trans-boundary livestock diseases such as Footand-mouth disease (FMD) have a direct economic impact by reducing agricultural and animal production (FAO/OIE, 2004; Domenech et al., 2006). Apart from causing suffering and mortality in susceptible population, the diseases adversely affect food safety, rural livelihoods, human health and international trade. The effect on national economy is felt by way of reduced access to international markets for the agricultural products and higher costs involved with inspection, treatment and compliance with international regulatory issues. Therefore it is necessary to effectively manage the transboundary diseases. In developing countries, control of these diseases is a key pathway for poverty alleviation. It is advisable to have an effective quarantine system in place to prevent entry and establishment of trans-boundary diseases. As a second line of defense, a country must also have in place a suitable contingency plans to respond quickly to high threat diseases. This could be achieved by timely application of scientific technology for rapid response. A disease outbreak in the neighboring country should always be taken as an immediate threat. Affected countries remain a threat to diseasefree nations and this is exemplified by recent incursions of FMD in FMD-free countries like Japan and Korea.

TRANS-BOUNDARY ANIMAL DISEASES (TADs)

The common ways of introduction of animal diseases to a new geographical location are through entry of live diseased animals and contaminated animal products. Other introductions result from the importation of contaminated biological products such as vaccines or germplasm or via entry of infected people (in case of zoonotic diseases). Even migration of animals and birds, or natural spreading by insect vectors or wind currents, could also spread diseases across geographical borders.

CHALLENGES IN DEALING WITH TADs

Several challenges confront the strategies to combat TADs (FAO, 2008; Hitchcock et al., 2007). The major ones are presented below: i. Requirement of novel systems having capacity of real-time surveillance of emerging diseases. For this, need driven research and service oriented scientific technology are a necessary at regional levels. Research emphasis has to be on specific detection and identification of the infectious agents.

ii. Need for epidemiological methods to assess the dynamics of infections in the self and neighboring countries/regions. These methods should be of real-time utility. iii. Need for research and development of disease diagnostic reagents those do not need refrigeration (cold chain). More importantly, they should be readily available as well as affordable, for use in pen-side test format. iv. There are many diseases for which there is inadequate supply of vaccines or there are no vaccines available. Insufficient or lack of vaccine hampers the disease control programmes. Need to build up vaccine banks for stockpiling the important vaccines to implement timely vaccination. v. Required availability of cost-effective intervention or disease control strategies. Even if a technology is available, it has to be cheaper to adopt at the point of use. vi. Need for ensuring public awareness of epidemic animal diseases. Many farmers are unaware of the emerging diseases. As such, unless reported to concerned regional authority, an emerging disease may go unnoticed. vii. Shortage of government and private funding for research on emerging animal disease problems. Government as well as industries dealing with animal health should take initiative and appropriate sponsorship in this regard. viii. Inadequate regulatory standards for safe international trade of livestock and livestock products. Otherwise, there would be a compromised situation in disease control strategies.

MANAGEMENT OF TADs

Various strategies need to be implemented to prevent and control trans-boundary diseases. These include:

i. Preventing incidence of trans-boundary diseases and disease transmitting vectors. Minimizing the movement of animals across the borders is essential. Also, prompt practice of quarantine protocol would reduce many transboundary diseases. Geographic information system (GIS) and remote sensing could be utilized as early warning systems and in the surveillance and control of infectious diseases (Martin et al., 2007). ii. Reducing man-made disasters that have adverse implications on climate. Global warming and climate change either due to natural or anthropogenic influences are likely to predispose the animal population to newer infections (FAO, 2008). Therefore collective efforts are needed to minimize adverse climatic changes. iii. Interrupting the human-livestockwildlife transmission of infections. Diseases at the wildlife–livestock interface must become the focus for surveillance of emerging infectious diseases (Siembieda et al., 2011). Breaking the cycle of disease transmission would help control the spread of infections. iv. Establishing regional biosecurity arrangement with capacity for early disease warning system for surveillance, monitoring and diagnosis of emerging disease threats (Domenech et al., 2006). v. Undertaking animal breeding strategies to create disease resistant gene pools. Enhancing host genetic resistance to disease by selective breeding of resistant animals is a smart strategy to improve natural immunity of animals to counter invading infections (Gibson et al., 2005). vi. Strengthening government policies to enhance agricultural/animal research and training, and technology development (Rweyemamu et al., 2006). More funds need to be allocated for this purpose to build goal oriented research programs in combating TADs. vii. Ensuring appropriate preparedness and response capacity to any emerging disease. Keeping in view that emerging infectious diseases are a constant threat, it is necessary to have early disease detection capacity and then implement a timely response (Hitchcock et al., 2007). viii. Intensification of international cooperation in preventing spread of TADs. As TADs are a concern globally, cumulative effort is needed at international level to minimize the spread of infectious diseases across the borders (Domenech et al., 2006; Hitchcock et al., 2007).

THE PRESENT ARRANGEMENTS ON INTERNATIONAL BASIS–

for dealing with transboundary epidemic diseases.

The control or eradication of livestock diseases is primarily the responsibility of national governments, whose executive for this purpose, is the national veterinary service.

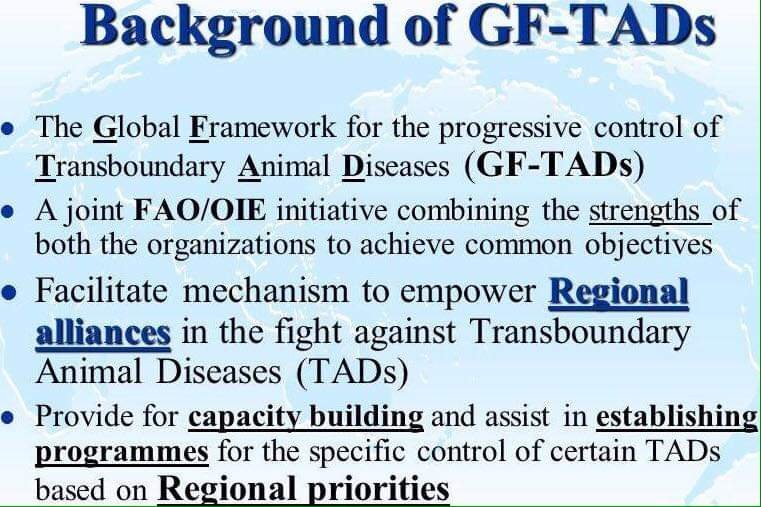

Veterinary services are aided in this task by various international organizations in addition to FAO and its regional commissions. These include:

• the OFFICE INTERNATIONAL DES EPIZOOTIES (OIE),

• the WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION (WHO), where the epidemic diseases of livestock also affect human health, and

• REGIONAL intergovernmental organizations such as the PAN AMERICAN HEALTH ORGANIZATION (PAHO) the EUROPEAN COMMISSION (EC) and the INTER-AFRICAN BUREAU FOR ANIMAL RESOURCES (IBAR) of the Organization of African Unity (OAU).

The OIE, based in Paris, has acquired de facto responsibility for developing and maintaining the zoosanitary norms necessary for international trade. To this end it has developed and Animal Health Code on which the international trade in animals and animal products should be based. It also maintains, in collaboration with FAO and WHO, an information system, to which all the member states contribute, that reports on the occurrence of disease outbreaks. The World Trade Organization (WTO) has given OIE technical responsibility for ensuring free and fair international trade (in live animals and animal products) under the recent GATT agreements; the OIE is developing risk assessment techniques for this purpose.

PAHO, EC and OAU-IBAR are examples of regional intergovernmental organizations that work towards developing an effective and common approach to disease control in their geographical territories. PAHO, through the PAN AMERICAN FMD CENTRE (PAFMDC) and the INTER-AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF FOOD PROTECTION AND ZOONOSES (INPPAZ), provides technical supports to countries in the Americas. The EC develops and maintains the sanitary conditions necessary for an open market within the European Union, while IBAR manages the Pan African Rinderpest Programme amongst other activities.

The FAO of the United Nations has been actively involved in the prevention and control of livestock diseases since its inception and has an Animal Health Service dedicated to this purpose. Increasingly it is focusing attention on the resurgence of serious epidemic diseases. This development has led to establishment of the livestock component of the EMPRES programme which is initially devoted to concerted action which focuses mainly, but not exclusively, on six of the most destructive epidemic diseases; selected because they dominated requests to FAO for assistance by member countries. They are:

RINDERPEST

FOOT AND MOUTH DISEASE

CONTAGIOUS BOVINE PLEUROPNEUMONIA

PESTE DES PETITS RUMINANTS

RIFT VALLEY FEVER

LUMPY SKIN DISEASE

Prior to the inception of EMPRES the arrangements were that when an epidemic of one of these diseases was reported, FAO took steps to help the national authorities in the infected territories and or to protect their neighbours, by organizing evaluation missions, securing the resources necessary for control e.g. vaccines, and supporting control programmes. These actions were generally carried out with financial support from the FAO TECHNICAL CO-OPERATION PROGRAMME (TCP) and less frequently with funds provided from other sources and arranged by FAO’s OFFICE FOR SPECIAL RELIEF OPERATIONS (OSRO now renamed TCOR).

The successful operation of these control programmes depends on FAO’s ability to draw on technical expertise, at short notice, from national and regional institutions and particularly from the international reference laboratories and collaborating centres which it sponsors on a continuing basis. These reference centres have been designated by FAO on the basis of their recognised excellence in regard to the diagnosis and control of certain specific animal diseases. They develop and maintain relevant diagnostic techniques, reagents and/or vaccine stocks and are capable of providing technical support in the event of a disease emergency.

THE LIMITATIONS OF THE TRADITIONAL ARRANGEMENTS

Despite the national and international disease control arrangements described above outbreaks of epidemic diseases of livestock have become increasingly frequent in certain regions. Food security is being threatened in many areas of subsistence agriculture. Several diseases, especially FMD, have made fresh incursions towards developed regions such as western Europe where there are dense livestock populations of highly susceptible animals. Risks increase as the international or trans-continental trade in animals and animal products, both legal or illegal, grows, and as the effectiveness of controls on this trade become less certain due to reduced support for national veterinary services.

Present arrangements often fail because they emphasize the control of disease epidemics after they have become widely disseminated rather their prevention at an earlier stage. The areas of endeavour that need to be strengthened include the following:-

• EARLY WARNING/FORECASTING: the OIE disease reporting arrangements depend on national authorities accurately reporting diseases occurring in their territories. Many countries are not consistent in reporting to OIE either because they do not have the technical resources to maintain adequate surveillance and diagnostic systems or, occasionally, because they wish to delay reporting the presence of disease so as to protect their export trade. These countries become foci of disease which threaten their neighbours and trading partners.

• THE PREVENTION OF TRANSBOUNDARY SPREAD: The recent international spread of epidemics illustrates how the ineffective control of animal movement within a country and ineffective border controls, exacerbated by the breakdown of public sector services in countries have led to serious epidemics. Recent epidemics of African swine fever in several African countries have been caused by lack of control over the movement of infected livestock and products, yet, this is not a problem confined to Africa. Recent epidemics of FMD in Italy, Greece, Malaysia and the Philippines were due to the illegal movement of infected animals and animal products, as were outbreaks of African swine fever in several African countries and, in Asia; rinderpest spread to Sri Lanka during a prolonged period of civil disturbances.

• PROMPT AND EFFECTIVE ACTION IN THE FACE OF AN INITIAL OUTBREAK OF DISEASE: Many countries are unprepared for disease epidemics. Some simply do not have the resources, others have devoted their resources to routine duties and few have developed the management disciplines necessary for prompt and effective action to overcome a new emergency. Inevitably there is a delay before the presence of the disease is recognised and a further delay before resources are mobilised. When FAO and other international bodies are called upon to assist there is an interval before appropriate emergency assistance programmes are drafted, approved and funds are released. Even when funds are released further delays arise due to the steps required for purchase and delivery of essential material inputs, particularly vaccines. A study of 22 vaccine purchases made during 1994 and 1995 for emergency disease control, with funding from TCP, OSRO or EMPRES, reveals that TCP projects required from 69 to 478 days from initial request to receipt of emergency supplies of vaccine, while EMPRES funded actions required from 40–118 days. Major delays were due to slow approval of funding and delays associated with delivery of vaccine with TCP projects. With EMPRES-supported actions delays were experienced with delivery of vaccine only. A major epidemic may develop in weeks or even days and these delays seriously impede the effectiveness of control actions.

• CONTINGENCY PLANNING: A number of FAO member states have prepared contingency plans for dealing with disease epidemics which ensure that the national authorities do have the necessary management structure, the legal capabilities and the resources for prompt and effective action. These countries include the USA, Australia, New Zealand and the member states of the European Union. This planning concept is being promoted in other parts of the world by FAO but it requires a change of attitude on the part of the national authorities. Early detection and immediate response to emergencies need to be recognised as integral parts of their disease control programmes.

• COMPETENT NATIONAL VETERINARY SERVICES: Disease preparedness programmes and eradication campaigns are best managed by an organization that has a short but direct chain of command, well trained personnel, and immediate access to financial and other resources. Many veterinary services operate within bureaucratic structures that hinder prompt and effective action and their management structures should be reviewed so as to improve their rapid response to emergencies and also to make best use of private as well as public sector resources.

• PUBLIC RELATIONS AND DISSEMINATION OF INFORMATION: The early detection and subsequent rapid reaction to epidemic disease outbreaks depends on the ability of livestock owners and local authorities to recognise and report rapidly suspected cases. Active promotion of public awareness campaigns in regard to target diseases is necessary to educate all non-technical personnel involved with livestock industries of the dangers of important epidemic diseases and the need for their detection, control and or eradication. Not only will this facilitate early detection but a fully informed industry is more likely to collaborate with and even demand the necessary control measures.

. THE FUTURE STRATEGY OF THE LIVESTOCK DISEASES COMPONENT OF EMPRES

The limitations of the arrangements for dealing with transboundary epidemic diseases of livestock have meant that controls failed to prevent the spread of rinderpest in Africa, the Middle East and South Asia, CBPP in Africa, and African Swine Fever in South America, the Caribbean, Africa and Europe. In some areas, disease eradication programmes have been outstandingly successful, notably FMD eradication in Europe and South America and rinderpest control in West and Central Africa, Ethiopia and India. However these advances remain under threat from incursions of disease from neighbouring infected areas.

The livestock disease component of the EMPRES programme seeks to emphasize the importance of preparing for, and if possible preventing, disease epidemics and ensuring prompt and effective action if they do occur.

EMPRES is confined to transboundary diseases i.e. “those that are of significant economic, trade and/or food security importance for a considerable number of countries; which can easily spread to other countries and reach epidemic proportions; and where control/management, including exclusion, requires co-operation between several countries”. The diseases for priority attention are those for which it is practical and economic to achieve control. Many other diseases are of economic and food security importance, e.g. trypanosomiasis and tick-borne diseases in cattle but these are not identified as priorities for the proactive programme because they fall outside the strict definition adopted for transboundary diseases.

EMPRES is likewise confined to emergencies and their prevention. A disease emergency is a sudden change in the distribution or incidence of a disease which if not corrected threatens transboundary herds and livestock production in one or more countries or regions.

FAO deals with animal diseases via the regular Agriculture Division programme, TCP arrangements and extra-budgetary funded field programmes. The EMPRES programme is intended to complement rather than supplement these activities. It has two major objectives. These are:

• EARLY WARNING, which comprises Contingency planning, Training, and Surveillance. These are clearly normative activities i.e. a set of tasks aimed at creating a standards and procedures by which disease-free status can be achieved and measured, with broad global applicability.

• EARLY REACTIONS, are essentially immediate and short-term actions in the field that may prevent the primary outbreak developing into a major epidemic and prevent the spread of the disease across national borders. EMPRES would include the provision of expert advice, diagnostic support as well as small amounts of vaccine and equipment. These actions precede the tasks of analysis and assessment that are essential preparation for operational projects requested by national governments.

The EMPRES sphere of activities relates to other FAO activities in disease control or emergency reaction as follows:

• THE ANIMAL HEALTH SERVICE – This service is responsible for a wide spectrum of on-going disease control programmes and animal health related activities apart from the new EMPRES initiative. AGAH activities in these fields are supported by collaboration from the Joint FAO/IAEA Division based in Vienna, FAO reference laboratories and collaborating centres.

• THE TECHNICAL CO-OPERATION PROGRAMME – This is, by its very nature, unprogrammed. It responds, with technical inputs from the Animal Health Service for animal diseases, to urgent and unforeseen demands from national governments and is essentially short term. TCP support is dependent on the receipt of an official government request; and could take over where a broad need for support is defined in the course of an EMPRES action. EMPRES early reaction is not constrained by the need for an official government request for support and fills a gap that TCP cannot presently address.

• THE OFFICE FOR SPECIAL RELIEF OPERATIONS – has the mandate to respond to requests for emergency assistance in the agricultural and livestock sectors submitted by countries affected by natural or man-made calamities. Where these calamities include the possibility of livestock disease epidemics, the EMPRES Unit can identify the urgent reactions required and assist in developing the necessary follow up with funding placed at TCOR disposal.

SUMMARY

With rapidly increasing globalization, an associated risk of movement of trans-boundary diseases is emerging. Trans-boundary animal diseases represent a serious threat. They reduce production and productivity, disrupt local and national economies, and also threaten human health. This imposes far-reaching challenges for agricultural scientists on the critically important need to improve technologies in animal production and health in order to ensure food security, poverty alleviation and to aid economic growth. Considering that livestock rearing constitutes a significant share in the national economy of a developing country like ours, it is imperative to take up disease control initiatives. Measures are required to safeguard the livestock industry from epidemics of infectious diseases and to uphold safe international trade of livestock and their products. In this regard, it is essential to develop scientific and risk-based standards that facilitate the international trade in animal commodities.