ACIDOSIS IN DAIRY CATTLE-TREATMENT & PREVENTION

Compiled & edited by-DR. RAJESH KUMAR SINGH, (LIVESTOCK & POULTRY CONSULTANT), JAMSHEDPUR, JHARKHAND,INDIA 9431309542, rajeshsinghvet@gmail.com

Rumen acidosis is a metabolic disease of cattle. Like most metabolic diseases it is important to remember that for every cow that shows clinical signs, there will be several more which are affected sub-clinically.

Acidosis is said to occur when the pH of the rumen falls to less than 5.5 (normal is 6.5 to 7.0). In many cases the pH can fall even lower. The fall in pH has two effects. Firstly, the rumen stops moving, becoming atonic. This depresses appetite and production.

Secondly, the change in acidity changes the rumen flora, with acid-producing bacteria taking over. They produce more acid, making the acidosis worse. The increased acid is then absorbed through the rumen wall, causing metabolic acidosis, which in severe cases can lead to shock and death.

Under extreme conditions, such as grain overload, large amounts of lactic acid are formed in the rumen. Acid may be produced faster than it can be absorbed or buffered. When lactic acid continues to build up, the rumen pH decreases (becomes more acidic) and microbial activity slows down. When the microbes stop working, fibre digestion is reduced and voluntary food intake is depressed.

In a normal, healthy rumen, lactic acid production equals lactic acid use. Thus, lactic acid is rarely detectable in a healthy rumen. However, a number of different factors can easily lead to an imbalance in lactic acid metabolism resulting in acute or sub-acute acidosis.

They include:

• Diet too high in fermentable carbohydrates.

• Too high concentrate:forage ratio.

• Too fast a switch from high forage to high concentrate.

• Too fast a switch from silage to high levels of green crop forage.

• Low fiber content in diet.

• Diet composed of very wet and highly fermented feeds.

• Too finely chopped forage.

• Over mixed TMR resulting in excess particle size reduction.

• Mycotoxins.

One of the most common causes of acidosis occurs when switching from a high fiber to high concentrate diet that is rich in fermentable carbohydrates (starches and sugars). Large amounts of starch and sugar stimulate bacteria that make lactic acid. In this instance, bacteria that normally use lactic acid cannot keep up with production. The amount of acidity in the rumen is measured by pH readings. The optimal rumen pH should be between 6.0 and 6.2, but there is daily fluctuation below this level even in healthy cows. Lactic acid is about ten times a stronger acid than the other rumen acids and causes the rumen pH to decrease. As the rumen pH drops below 6.0, bacteria that digest fiber begin to die and thus, fiber digestion is depressed. Because the end products of fiber digestion are used for milk fat synthesis, a drop in milk fat test is a sure sign of acidosis. In, addition, the accumulation of acid causes an influx of water from the tissues into the gut and thus a common sign of acidosis is diarrhea. If the rumen pH continues to decline and falls below 5.5, many other normal healthy rumen bacteria also begin to die. As lactic acid accumulates, it is absorbed and lowers the pH of the blood. High levels of acid in the gut can also cause ulcers in the rumen resulting in infiltration of bacteria into the blood that can cause liver abscesses. Endo-toxins resulting from high acid production in the rumen also affects blood capillaries in the hoof, causing them to constrict resulting in laminitis. Sub-acute acidosis is also characterized by cycling intake because animals eat less during times of distress, then if the rumen adapts, their appetite returns. If blood pH drops too low, this can result in death of the animal in acute acidosis.

Another common cause of acidosis is having diets too low in effective fiber (see last newsletter) or too small particle size. When animals don’t chew their cud normally, lack of saliva (that contains a natural buffer) contributes to low rumen pH. Recently, researchers at the University of Wisconsin have found that some mycotoxins can alter the metabolism of lactic acid causing it to build up and cause acidosis. This may explain why acidosis and laminitis are also commonly observed when mycotoxins are a problem.

The common symptoms of acidosis include: —————–

• Low milk fat test; < 3.0 to 3.3%.

• Sore hooves; laminitis.

• Cycling feed intake.

• Diarrhea.

• Liver abscesses.

• Low rumen pH (< 5.8) in 30 to 50% of animals tested.

• Limited cud chewing.

Veterinarians and nutritionists also use a procedure called rumenocentesis to measure rumen acidity. A needle is pushed through the flank of the animal into the rumen and ruminal fluid is withdrawn into a syringe. The rumen fluid is then measured with a pH meter. In my opinion, a low milk fat test (less than 3.3 to 3.0%) is one of the best measures of acidosis. Fat tests less than 2.7 to 2.8% will more than likely be accompanied by cows with laminitis. In order to prevent acidosis good management practices are needed to prevent the situations in Table 1 from occurring. Several pounds of long hay (or even straw) can go a long way in helping cows but the root of the problem must be found and corrected. Buffers can also be useful in keeping rumen pH high, especially in corn silage-based diets. Use common sense when changing diets and ensure that there is effective fiber in your diets for production of saliva.

Also to avoid acidosis, grain should be introduced gradually (ie. 0.5 kg grain or

pellets/cow/day) so that the population of rumen microbes can adjust according to the type of fermentation that is required (more starch fermenting microbes may be needed). Remember, though, that different cows respond differently to grain feeding. Some cows can handle 6 kg of grain per day while others will get sick on 3 kg per day and there is always a cow that will eat more than her share. The key to success is to make it a gradual daily increase and to WATCH your cows and check for symptoms of acidosis or grain poisoning.

Treatment-————

Because subacute ruminal acidosis is not detected at the time of depressed ruminal pH, there is no specific treatment for it. Secondary conditions may be treated as needed.

=> Thiamine is often a highly recommended injection to give to cattle with acute acidosis, as it is very important in treating and stopping a sudden acidosis attack. Acidosis very often halts the production of thiamine through digestion, and an injection of Thiamine will reverse this process.

=> Baking soda will also work as a treatment for cattle with acidosis.

=> it is believed that restricting water intake for the first 18–24 hr is helpful, although this has not been proven.

=>Removal of rumen contents and replacement with ingesta taken from healthy animals is necessary.

=> In animals that are still standing, rumenotomy is preferred to rumen lavage, because animals may aspirate during the lavage procedure and only rumenotomy ensures that all ingested grain has been removed.

=>Rumen lavage may be accomplished with a large stomach tube if sufficient water is available. A large-bore tube (2.5 cm inside diameter, 3 m long) should be used, and enough water added to distend the left paralumbar fossa; gravity flow is then allowed to empty out what it will. Repeating this 15–20 times achieves the same results

=>Fluid therapy to correct the metabolic acidosis and dehydration and to restore renal function. Initially, over a period of ∼30 min, 5% sodium bicarbonate solution should be given IV (5 L/450 kg). During the next 6–12 hr, a balanced electrolyte solution, or a 1.3% solution of sodium bicarbonate in saline, may be given IV, up to as much as 60 L/450 kg body wt.

=>Administer antacids PO (or intraruminally), particularly if IV sodium bicarbonate has been administered.

=>Procaine penicillin G should be administered IM to all affected animals for at least 5 days to minimize the development of bacterial rumenitis and liver abscesses.

=>Thiamine should also be administered IM to facilitate metabolism of l-lactate via pyruvate and oxidative phosphorylation; grain overload animals also have low concentrations of thiamine in rumen fluid due to the increased production of thiaminase by ruminal bacteria.

=>Next 2–4 days, good-quality hay and no grain should be given, and the grain then reintroduced gradually.

=> If good appetite returns within 3 days, the prognosis is good. However, if treatment was not started early enough to prevent acidification of the ruminal contents, and mycotic infection of the rumen wall ensues, relapse is likely within 3–5 days, and the prognosis is grave.

Homeopathic Treatment :

1. Correct the dietic errors and transfering 3 liters of ruminal fluid, from

healthy to affected.

2. Nat. carb 30 Dose: 10 drops in a cup of water, for

+ every 15-30 mts, till relief Obtained.

Mag. carb 30

2. Colochicum 30: when too much green fodder is fed, and when ruminal

tympany followed.

Dose : 1 Dose every 2 hrs till relief

4. Carboveg 30 : when the animal is in collapsable condition, when colic and

tympany with difficulty in respiration.

Dose : Q.I.D.

5. Nux vomica 30

Mag phos 30

Corbo veg 30

Pulsatilla 30 aa 1 ml

Dose : 10 drops 3 to 4 times per day.

6. Natrum phos 6x : 10 pills in 30 ml water 6 times for 3-4 days.

Prevention——————–

Nutritional management for prevention of sub acute ruminal acidosis (SARA)——

____________________________________________________

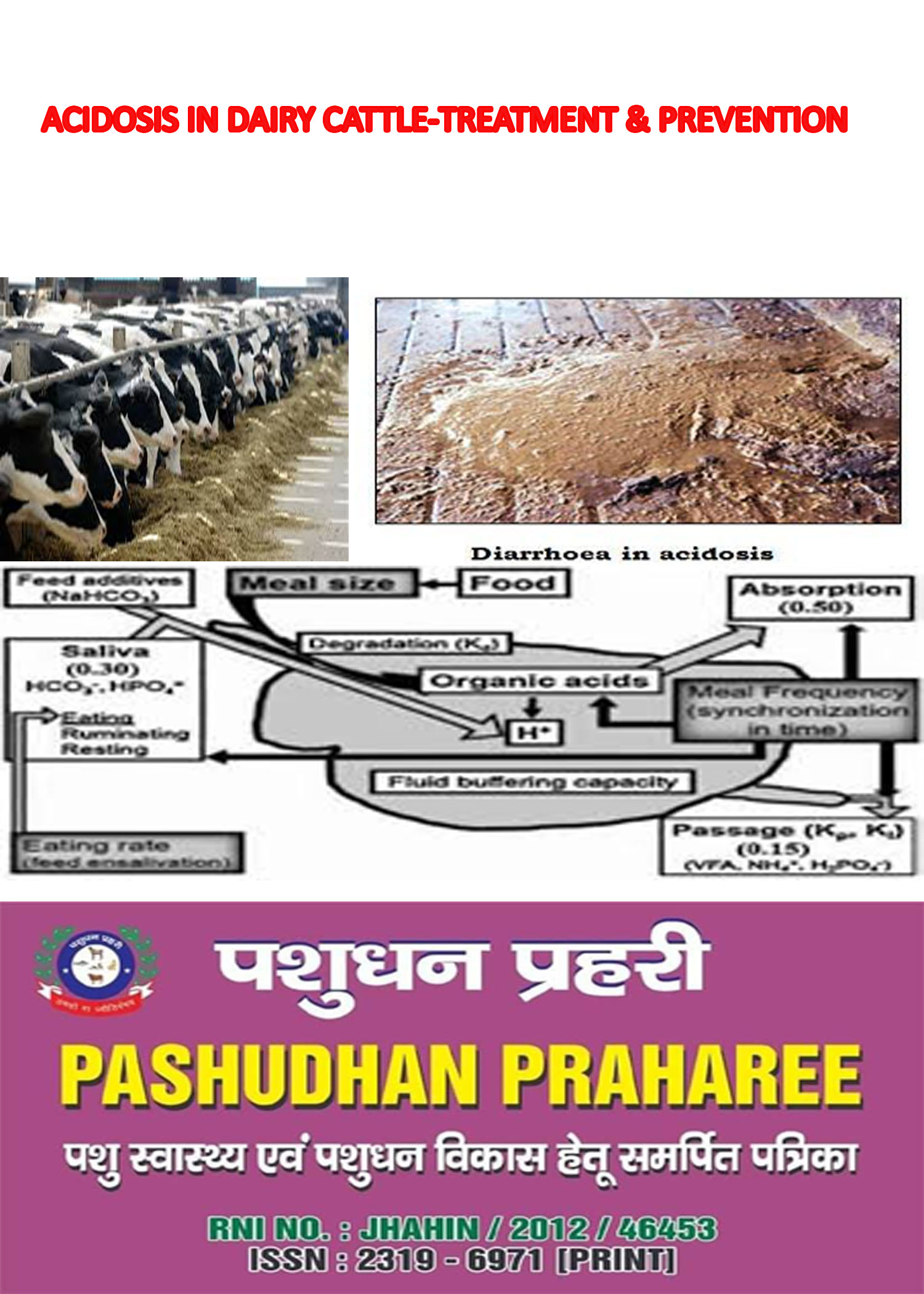

Fermentation acid production in the rumen needs to be balanced with fermentation acid removal and neutralization in order to achieve optimal ruminal conditions and optimal production. When this balance between acid production and acid removal/neutralization is not achieved the cow will suffer from SARA. Consequently, causes of SARA in dairy herds may be grouped into three major categories:

1.Excessive intake of rapidly fermentable carbohydrates,

2. Inadequate ruminal adaptation to a highly fermentable diet.

3. Inadequate ruminal buffering caused by inadequate dietary fiber and/or inadequate physical fiber.

1.Excessive intake of rapidly fermentable carbohydrates:

___________________________________________

Excessive intake of rapidly fermentable carbohydrates is the most obvious cause of ruminal acidosis. An important goal of effective dairy cow nutrition is to feed as much concentrate as possible, in order to maximize production, without causing ruminal acidosis. This is a difficult and challenging task because the indications of feeding excessive amounts of fermentable carbohydrates (decreased DM intake and milk production) are very similar to the results from feeding excessive fibre (again, decreased DM intake and milk production).An important distinction is that even slightly over-feeding fermentable carbohydrates causes long-term health problems, while slightly under-feeding fermentable carbohydrates reduces milk yield but does not compromise cow health.

Controlling the level and type of NFC(Non Fibre Carbohydrate) in the ration is essential to preventing ruminal acidosis. Dietary NFC includes organic acids, sugars, starch and soluble fiber such as pectic substances. It is suggested by some to restrict NFC to 350–400 g/kg of diet DM when the NFC is largely sugar or starch or to 400–500 g/kg when other carbohydrates predominate.. In feedlot cattle, a greater risk of ruminal acidosis has been reported when more rapidly fermented grain sources such as wheat and steam-flaked sorghum are fed. Particle size analysis of grains is a useful adjunct test when assessing the risk for SARA in a dairy herd. However, total intake of rapidly fermentable carbohydrates is probably more important than NFC percentage in the diet. Herds or groups within herds with higher DM intakes are at inherently higher risk for SARA and should be fed lower NFC diets than other herds or groups.

Dairy herds that use component feeding often increase grain feeding in early lactation faster than the expected rise in DM intake. This puts cows at great risk for SARA, because they cannot eat enough forage to compensate for the extra grain consumed. Declining forage intake in early post-partum cows has also been demonstrated in herds where concentrate feeding was increased too rapidly.

Evaluating the dietary content for both fiber and non-fiber carbohydrates is an important first step in determining the cause of SARA in a dairy herd. This requires a careful evaluation of the ration actually being consumed by the cows. Ascertaining the ration actually consumed by the cows requires a careful investigation of how feed is delivered to the cows, accurate weights of the feed delivered and updated nutrient analyses of the feeds delivered particularly DM content of the fermented feed ingredients.

2.Inadequate adaptation to highly fermentable, high carbohydrate diets :-————-

____________________________________________________

Ruminal adaptation to diets high in fermentable carbohydrates apparently has two key aspects, microbial adaptation and lengthening of the ruminal papillae. These principles suggest that increasing grain feeding toward the end of the dry period should decrease the risk for SARA in early lactation cows

The key to prevention is reducing the amount of readily fermentable carbohydrate consumed at each meal. This requires both good diet formulation (proper balance of fiber and nonfiber carbohydrates) and excellent feed bunk management. Animals consuming well-formulated diets remain at high risk for this condition if they tend to eat large meals because of excessive competition for bunk space or following periods of feed deprivation.

Feeding excessive quantities of concentrate and insufficient forage results in a fiber-deficient ration likely to cause subacute ruminal acidosis. The same situation may be seen during the last few days before parturition if the ration is fed in separate components.

Including long-fiber particles in the diet reduces the risk of subacute ruminal acidosis by encouraging saliva production during chewing and by increasing rumination after feeding. However, long-fiber particles should not be easily sorted away from the rest of the diet; this could delay their consumption until later in the day or cause them to be refused completely.

Ruminant diets should also be formulated to provide adequate buffering. This can be accomplished by feedstuff selection and/or by the addition of dietary buffers such as sodium bicarbonate or potassium carbonate. Dietary anion-cation difference is used to quantify the buffering capacity of a diet.

Supplementing the diet with direct-fed microbials that enhance lactate utilizers in the rumen may reduce the risk of subacute ruminal acidosis. Yeasts, propionobacteria, lactobacilli, and enterococci have been used for this purpose. Ionophore (eg, monensin sodium) supplementation may also reduce the risk by selectively inhibiting ruminal lactate producers.

Reference-on request