BEWARE OF “TICKING BOMB”-THE CRIMEAN-CONGO HEMORRHAGIC FEVER (CCHF)

Compiled, & shared by-DR. RAJESH KUMAR SINGH, (LIVESTOCK & POULTRY CONSULTANT), JAMSHEDPUR Post no 1411 Dt 23/09//2019

JHARKHAND,INDIA 9431309542, rajeshsinghvet@gmail.com

Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF) is a zoonotic viral disease that is asymptomatic in infected animals, but a serious threat to the health of humans. Human infections begin with non-specific febrile symptoms, but progresses to a serious haemorrhagic syndrome with a high case fatality rate.

Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF) is caused by infection with a tick-borne virus (Nairovirus) in the family Bunyaviridae. The disease was first characterized in the Crimea in 1944 and given the name Crimean hemorrhagic fever. It was then later recognized in 1969 as the cause of illness in the Congo, thus resulting in the current name of the disease. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever is found in Eastern Europe, particularly in the former Soviet Union, throughout the Mediterranean, in northwestern China, central Asia, southern Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and the Indian subcontinent.

CCHF is caused by the CCHF virus (CCHFV), a member of the genus Nairovirus in the family Bunyaviridae. The virus is stable for up to 10 days in blood kept at 40°C.

Although the causative virus is often transmitted by ticks, animal-to-human and human-to-human transmission also occurs. CCHF affects mostly adults (no case has been reported in children under 15 in South Africa since 1993) and is endemic in many countries in Africa, Europe and Asia. During 2001, cases or outbreaks were recorded in Iran, Pakistan, South Africa with the latest being in India. It has also been found in parts of Europe including southern portions of the former USSR (Crimea, Astrakhan, Rostov, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Tajikistan), Turkey, Bulgaria, Greece, Albania and Kosovo (a province of the former Yugoslavia). Limited serological evidence suggests that CCHFV might also occur in parts of Hungary, France and Portugal. Eight years ago CCHF outbreak occurred in January 2011 in the state of Ahmedabad (India) but the most recent out break of CCHF has been confirmed few days ago in Jaipur,Rajsthan, India from the test report of NIV, PUNE.

In this outbreak this rare deadly virus killed three people. The patients died due to multiple organ failure, specifically failure of the liver and kidney. The National Institute of Virology (NIV), (Pune, India) confirmed that all three patients were infected with the CCHF virus. The NIV is testing some 50 samples from the area, and the Rajsthan government, warning of a possible outbreak, has begun a screening exercise covering affected villagers.

This is the 2nd time that CCHF case has been reported in India . Reasons for the outbreak of CCHF in India include climate and anthropogenic factors such as changes in land use, agricultural practices or hunting activities, and movement of livestock that may influence host-tick-virus dynamics.

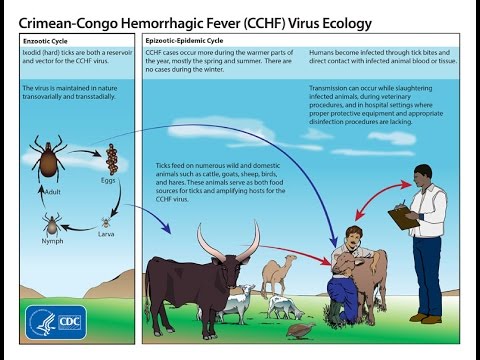

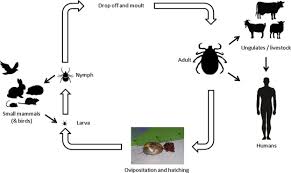

The CCHF virus may infect a wide range of domestic and wild animals, with the occurrence of this virus correlated with the distribution of a particular species of tick. A number of tick genera are capable of becoming infected with the CCHF virus, but the most efficient and common vectors for CCHF appear to be members of the Hyalomma genus. Trans-ovarial (transmission of the virus from infected female ticks to offspring via eggs) and venereal transmission have been demonstrated amongst some vector species, indicating one mechanism which may contribute to maintaining the circulation of the virus in nature.Many birds are resistant to infection, but ostriches are susceptible and may show a high prevalence of infection in endemic areas. Animals become infected with CCHF from the bite of infected ticks.

However, the most important source for acquisition of the virus by ticks is believed to be infected small vertebrates on which immature Hyalomma ticks feed. Once infected, the tick remains infected through its developmental stages, and the mature tick may transmit the infection to large vertebrates, such as livestock. Domestic ruminant animals, such as cattle, sheep and goats, are viraemic (virus circulating in the bloodstream) for around one week after becoming infected.

Humans acquire CCHF in two different ways; through a tick bite or contact or by contagion. The sources of exposure include being bitten by a tick (happening, occasionally when individuals squash them between their fingers as a means of self-protection), contacting animal blood or tissues, and drinking unpasteurised milk. Human-to-human transmission can occur, particularly when skin or mucous membranes are exposed to blood during haemorrhages or tissues during surgery. This disease is a particular threat to farmers and other agricultural workers, veterinarians, laboratory workers and hospital personnel. Infection more commonly occurs in people who have outdoor occupations such as farmers, dairymaids or woodsmen.

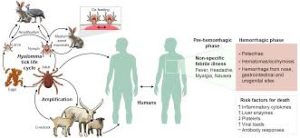

The first sign of CCHF is a sudden onset of fever and other non-specific symptoms including chills, severe headache, dizziness, photophobia, neck pain, myalgia and arthralgia and the accompanying fever may be very high. Gastrointestinal symptoms including nausea, vomiting, non-bloody diarrhoea and abdominal pain are also common. It is followed, after several days, by the haemorrhagic phase.

The hemorrhagic phase develops suddenly. It is usually short, lasting on average two to three days. A petechial rash may be the first symptom. The rash is followed by petechiae, ecchymoses and large bruises on the skin and mucous membranes. Hematemesis, melena, epistaxis, haematuria, haemoptysis and bleeding from venepuncture sites are also common. Some patients die from haemorrhages, haemorrhagic pneumonia or cardiovascular disturbances. In patients who survive, recovery begins 10 to 20 days after the onset of illness.

CCHF can be diagnosed by isolating CCHFV from blood, plasma or tissues. It is often diagnosed using RT-PCR on blood samples. This technique is highly sensitive. Viral antigens can be identified with enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) or immunofluorescence, but this test is less sensitive than PCR.CCHF can also be diagnosed by serology. Tests detect CCHFV- specific IgM, or a rise in IgG titres in paired acute and convalescent sera.

The average case fatality rate is 30–50%, but mortality rates from 10% to 80% have been reported in various outbreaks. The mortality rate is usually higher for nosocomial infections than after tick bites; this may be related to the virus dose.Particularly high mortality rates have been reported in some outbreaks from the United Arab Emirates (73%) and China (80%). Due to the high case fatality rates and difficulties in treatment, prevention, and control, CCHF is a disease which should be notified to the public health authorities immediately. CCHF virus is also in the list of agents for which the Revised International Health Regulations of 2005 call for implementation of the decision algorithm for risk assessment and possible notification to the World Health Organization (WHO).

General supportive therapy is the mainstay of patient management in CCHF. Intensive monitoring to guide volume and blood component replacement is required. The WHO recommends Ribavirin for the treatment of CCHF cases. Ribavirin is believed to improve the prognosis if administered before day five after the onset of illness. Both oral and intravenous formulations seem to be effective. Passive immunotherapy with hyperimmune serum has been tested in a few cases, but the value of this treatment is controversial.

Transmission ————–

Ixodid (hard) ticks, especially those of the genus, Hyalomma, are both a reservoir and a vector for the CCHF virus. Numerous wild and domestic animals, such as cattle, goats, sheep and hares, serve as amplifying hosts for the virus. Transmission to humans occurs through contact with infected ticks or animal blood. CCHF can be transmitted from one infected human to another by contact with infectious blood or body fluids. Documented spread of CCHF has also occurred in hospitals due to improper sterilization of medical equipment, reuse of injection needles, and contamination of medical supplies.

Signs and Symptoms ————-

The onset of CCHF is sudden, with initial signs and symptoms including headache, high fever, back pain, joint pain, stomach pain, and vomiting. Red eyes, a flushed face, a red throat, and petechiae (red spots) on the palate are common. Symptoms may also include jaundice, and in severe cases, changes in mood and sensory perception. As the illness progresses, large areas of severe bruising, severe nosebleeds, and uncontrolled bleeding at injection sites can be seen, beginning on about the fourth day of illness and lasting for about two weeks. In documented outbreaks of CCHF, fatality rates in hospitalized patients have ranged from 9% to as high as 50%. The long-term effects of CCHF infection have not been studied well enough in survivors to determine whether or not specific complications exist. However, recovery is slow.

Risk of Exposure ————-

Animal herders, livestock workers, and slaughterhouse workers in endemic areas are at risk of CCHF. Healthcare workers in endemic areas are at risk of infection through unprotected contact with infectious blood and body fluids. Individuals and international travelers with contact to livestock in endemic regions may also be exposed.

Diagnosis —————-

Laboratory tests that are used to diagnose CCHF include antigen-capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), real time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), virus isolation attempts, and detection of antibody by ELISA (IgG and IgM). Laboratory diagnosis of a patient with a clinical history compatible with CCHF can be made during the acute phase of the disease by using the combination of detection of the viral antigen (ELISA antigen capture), viral RNA sequence (RT-PCR) in the blood or in tissues collected from a fatal case and virus isolation. Immunohistochemical staining can also show evidence of viral antigen in formalin-fixed tissues. Later in the course of the disease, in people surviving, antibodies can be found in the blood. But antigen, viral RNA and virus are no more present and detectable.

Treatment ————

Treatment for CCHF is primarily supportive. Care should include careful attention to fluid balance and correction of electrolyte abnormalities, oxygenation and hemodynamic support, and appropriate treatment of secondary infections. The virus is sensitive in vitro to the antiviral drug ribavirin. It has been used in the treatment of CCHF patients reportedly with some benefit.

Recovery———–

The long-term effects of CCHF infection have not been studied well enough in survivors to determine whether or not specific complications exist. However, recovery is slow.

Prevention——————–

Agricultural workers and others working with animals should use insect repellent on exposed skin and clothing. Insect repellants containing DEET (N, N-diethyl-m-toluamide) are the most effective in warding off ticks. Wearing gloves and other protective clothing is recommended. Individuals should also avoid contact with the blood and body fluids of livestock or humans who show symptoms of infection. It is important for healthcare workers to use proper infection control precautions to prevent occupational exposure.

Prevention and control:

• Personal protective measures like avoidance of areas where tick vectors are abundant and when they are active (spring to autumn); regular examination of clothing and skin for ticks, and their removal; and use of repellents in those persons living in endemic areas.

• Persons who work with livestock or other animals can take protective measures like the use of repellents on the skin (e.g. DEET) and clothing (e.g. permethrin) and wearing gloves or other protective clothing to prevent skin contact with infected tissue or blood.

• When patients with CCHF are admitted to hospital, there is a risk of nosocomial spread of infection. In the past, serious outbreaks have occurred in this way and it is imperative that adequate infection control measures be observed to prevent this disastrous outcome. Patients with suspected or confirmed CCHF should be isolated and cared for using barrier nursing techniques.

• Specimens of blood or tissues taken for diagnostic purposes should be collected and handled using universal precautions. Sharps (needles and other penetrating surgical instruments) and body wastes should be safely disposed of using appropriate decontamination procedures.

• Healthcare workers (HCW) who have had contact with tissue or blood from patients with suspected or confirmed CCHF should be followed up with daily temperature and symptom monitoring for at least 14 days after the putative exposure.

• Contact tracing and follow up of family, friends and other patients, who may be exposed to a CCHF virus through close contact with the infected HCW is essential.

• There is no safe and effective vaccine available for human use. Although an inactivated, mouse brain-derived vaccine against CCHF has been developed and used on a small scale in Eastern Europe. The acaricides (chemicals intended to kill ticks) is only a realistic option for well-managed livestock production facilities.