Canine Crisis Management: Navigating Parvovirus – Diagnosis, Prevention and Therapeutic Approaches

Bhand Akshata Chandrakant1, Deshmukh Kaivalya Ruprao2

1PhD Scholar, Division of Medicine, Indian Veterinary Research Institute, Izatanagar, Bareilly – 243122. Email ID – drakshatavmc@gmail.com

2M.V.Sc Scholar, Division of Animal Biochemistry, Indian Veterinary Research Institute, Izatanagar, Bareilly – 243122. Email ID – kaivalya.deshmukh17@gmail.com

Abstract:

Canine parvovirus is often blamed for both puppy mortality and hemorrhagic diarrhea in many parts of the world (CPV). The Minute Virus of Canine (CPV) is found in two forms: CPV-1 and CPV-2. Three CPV-2 variations—2a, 2b, and 2c—are the result of genetic alterations. A clinical examination, in-house assays, and PCR are used in the diagnosis process. Hygiene, a rigorous quarantine period, and early puppy immunizations are all part of prevention. Blood transfusions are used in extreme circumstances along with supportive care, intravenous hydration, and medication to relieve symptoms. For efficient CPV management and canine health protection, an integrated strategy emphasizing early diagnosis, prevention, and prompt treatment is essential.

Keywords : Canine Parvovirus, Life Cycle,Symptoms, Risk Assessment , Diagnosis, Prevention and Treatment

Introduction: Canine parvovirus-2 (CPV-2) is a major enteropathogen that causes gastroenteritis in dogs and puppies. It is an icosahedral capsid virus that is non-enveloped and contains single stranded DNA. Canine parvovirus-1 (CPV-1), also known as Minute Virus of Canine, is genetically unrelated to CPV-2. The primary capsid protein, VP2, controls the antigenicity of the virus within the capsid. The virus was initially discovered as a host range variation of the feline panleukopenia virus (FPV). Acute hemorrhagic diarrhea caused by the extremely infectious and deadly CPV-2 virus frequently results in mortality (>70% in pups and <1% in adult dogs) and 100% morbidity worldwide .Following the discovery of the first parvoviral infection case in 1979, the virus underwent genetic changes at the VP2 capsid protein, resulting in the development of its three variants (CPV-2a, CPV-2b, and CPV-2c). One of the most common gastroenteritis viruses in the world, CPV-2 is found mostly in the United States of America (USA), Brazil, Belgium, Australia, Denmark, Japan, and France [Miranda et al.,2016]. Hemorrhagic diarrhea and, in rare cases, myocarditis are the main clinical symptoms linked to CPV-2 [Tavora et al.,2008]. It is known that CPV-2 infection may exist in kennels that have had vaccinations. The virus is extremely infectious and may spread through inanimate things and the fecal-oral pathway. Clinical symptoms linked to CPV-2 are frequently non-specific and manifest as fever, tiredness, and sadness. Dogs who have hemorrhagic diarrhea and vomiting, which typically begin 24 hours after infection, suffer from acute dehydration. The timely detection of CPV-2 is crucial in mitigating the propagation of the virus, particularly during the first stages of infection. The majority of CPV-2 detection techniques are based on molecular and immunological techniques [Nandi et al.,2010]. Numerous vaccinations, including modified live viruses and heat-killed versions, have been created to manage the illness [Nandi et al.,2010]. The main causes of vaccine failure include interaction with antibodies produced from the mother, improper immunization timing, and, less frequently, viral vaccine reversion [Bull j et al.,2015 ] and [Altman et al.,2017]. Although a number of post-exposure medicines have been developed to treat the condition, their cost and availability are limited [Mylonakis et al.,2016].To address the issues related to CPV-2 infection, more advancements are necessary in the fields of diagnostics, surveillance instruments, and pre- and post-exposure therapy. This article aimed to provide information regarding , clinical diagnosis, treatments and prevention of CPV-2.

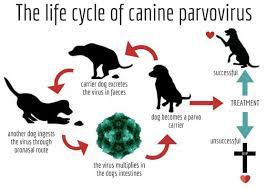

Life cycle:

Clinical symptoms:

CPV-2 infection in dogs typically begins with a gradual onset of fever, followed by vomiting and diarrhea, often with stool appearing yellow or bloody. Clinical symptoms manifest 3 to 5 days post-infection and endure for 5–7 days [Nandi et al.,2010]. Signs include anorexia, depression, lethargy, profuse or hemorrhagic diarrhea, abdominal discomfort, pyrexia, dehydration, and, in severe cases, death [Ogbu et al.,2017]. Leukopenia may occur, with a white blood cell count dropping below 2000–3000 cells/mL [Decaro et al .,2012]. The duration of infection is influenced by the ingested virus load. Mortality and morbidity rates vary based on challenge severity, age, and co-infection. In co-infection, CPV-2 can lead to complications like septicemia, endotoxemia, systemic inflammation, coagulation disorders, and septic shock. Pulmonary infection may result in respiratory distress, while myocarditis is a rare manifestation in puppies below 3 months. Chronic infection leads to agonal breathing, and while mild cases may undergo outpatient treatment [Nandi et al.,2010], it’s often discouraged due to challenges in timely oral treatment, leading to deterioration.

Risk factors:

Canine Parvovirus type 2 (CPV-2) can infect dogs of any age, sex, or breed. Young puppies, especially those between weaning and six months, are more susceptible, influenced by the level of maternal antibody protection acquired from colostrum [Decaro et al., 2008]. Other risk factors include insufficient vaccination, contributing to increased susceptibility, and the crucial role of vaccination in preventing and reducing CPV severity.Maternal antibody protection from colostrum is essential, with lower levels increasing the risk [Decaro et al., 2005]. Environmental factors, such as high concentrations of dogs in kennels, elevate the risk of CPV transmission [Decaro et al., 2008]. Additionally, certain breeds may have higher susceptibility due to genetic factors or immune response variations [Decaro et al., 2008].

Diagnosis:

The diagnosis of canine parvovirus (CPV) disease typically involves a combination of clinical evaluation, laboratory tests, and imaging. Clinical signs, including vomiting, bloody diarrhea, lethargy, and anorexia, are considered indicative of CPV infection. A common diagnostic approach is the analysis of fecal samples using tests such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to detect the presence of the virus [Decaro et al., 2005]. Blood tests may be employed to assess the white blood cell count and identify a decrease in lymphocytes, a characteristic of CPV infections. Additionally, imaging techniques like radiographs or ultrasound may be utilized to evaluate the condition of the intestines and other abdominal organs [Decaro et al., 2005].

Prevention and Treatment:

Preventing canine parvovirus (CPV) infection requires vaccination, strict hygiene practices, and minimizing exposure to contaminated areas. It is crucial to initiate vaccination at 6 to 8 weeks, provide boosters until 16 weeks, and administer periodic boosters for adults [Day et al., 2016; Greene, 2012]. To counter CPV’s resistance, maintain rigorous hygiene by cleaning with effective disinfectants .Swiftly isolate infected dogs to prevent transmission and restrict exposure to high-density dog environments [Day et al., 2016]. Regular veterinary check-ups are essential for the early detection of health issues [Day et al., 2016].

Treatment: General Guidelines For Treatment Of Canine Parvoviral Eneteritis Ref:[Small animal internal medicine –Richard w. Nelson]

References:

1]Decaro, N., Desario, C., Addie, D. D., Martella, V., Vieira, M. J., Elia, G., … & Buonavoglia, C. (2008). The study molecular epidemiology of canine parvovirus, Europe. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 14(8), 1232-1239.

2]Decaro, N., Elia, G., Martella, V., Desario, C., Campolo, M., Trani, L. D., … & Buonavoglia, C. (2005). A real-time PCR assay for rapid detection and quantitation of canine parvovirus type 2 in the feces of dogs. Veterinary Microbiology, 105(1), 19-28.

3]Schultz, R. D. (2006). Duration of immunity for canine and feline vaccines: a review. Veterinary Microbiology, 117(2-4), 75-79.

4]Decaro, N., Desario, C., Elia, G., Martella, V., Mari, V., Lavazza, A., … & Buonavoglia, C. (2005). Serological and molecular evidence that canine respiratory coronavirus is circulating in Italy. Veterinary Microbiology, 110(1-2), 45-50.

5]Day, M. J., Horzinek, M. C., & Schultz, R. D. (2016). Suggested guidelines for using systemic antimicrobials in bacterial skin infections: part 2—antimicrobial choice, treatment regimens, and compliance. Veterinary Dermatology, 27(2), 82-e25.

6]Greene, C. E. (2012). Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. Elsevier Health Sciences.

7]Carmichael, L. E. (2005). An annotated historical account of canine parvovirus. Journal of Veterinary Medicine Series B, 52(7-8), 303-311.

8]M.J. Appel, F.W. Scott, L.E. Carmichael, Isolation and immunisation studies of a canine parvo-like virus from dogs with haemorrhagic enteritis, Vet. Rec. 105 (8) (1979) 156–159.

9]J.W. Black, M.A. Holscher, H.S. Powell, C.S. Byerly, Parvoviral enteritis and panleucopenia in dogs, J. Med. Small Anim. Clin. 74 (1979) 47–50.

10]C. Miranda, G. Thompson, Canine parvovirus: the worldwide occurrence of antigenic variants, J. Gen. Virol. 97 (9) (2016) 2043–2057.

11]F. Tavora, L.F. Gonzalez-Cuyar, J.S. Dalal, T. O’Malley, M. Zhao, R. Peng, H.Q, A. P. Burke, Fatal parvoviral myocarditis: a case report and review of literature, Diagn. Pathol. 3 (1) (2008) 21.

12]S. Nandi, M. Kumar, Canine parvovirus: current perspective, Indian Journal of virology 21 (1) (2010) 31–44.

13]J.J. Bull, Evolutionary reversion of live viral vaccines: can genetic engineering subdue it? Virus Evol. 1 (1) (2015) vev005.

14]K.D. Altman, M. Kelman, M.P. Ward, Are vaccine strain, type or administration protocol risk factors for canine parvovirus vaccine failure? Vet. Microbiol. 210 (2017) 8–16.

15]M.E. Mylonakis, I. Kalli, T.S. Rallis, Canine parvoviral enteritis: an update on the clinical diagnosis, treatment, and prevention, Vet. Med. Res. Rep. 7 (2016) 91.

16]K.I. Ogbu, B. Anene, N.E. Nweze, J.I. Okoro, M. Danladi, S. Ochai, Canine parvovirus. A review, Int. J. Sci. Appl. Res. 2 (2) (2017) 74–95.

17]N. Decaro, C. Buonavoglia, Canine parvovirus—a review of epidemiological and diagnostic aspects, with emphasis on type 2c, Vet. Microbiol. 155 (1) (2012) 1–12.