Control of External Parasites of Sheep and Goats

External parasitism results in poor quality sheep and goat products especially skins and lost income to producers. Common external sheep and goat parasites include ticks, lice, keds and mites. Some parasites feed on blood causing blood-loss anemia, especially in young animals. The result is unthrifty, poor-performing sheep and goats.A regular program of treatment and prevention of external parasites should be an important part of a flock health program. The benefits of an effective external parasite control program include increased comfort for animals, improved performance, and higher quality of products.

Effects of external parasites

External parasites limit production in sheep and goats in many ways and result in economic loss. The following are some of the major ones:

- Attachment to the host causes irritation of the skin with subsequent ulceration and secondary infections.

- They feed on body tissue such as blood, skin, and hair. Heavy infestations are associated with anemia (adult female ticks can, for example, suck up to 10 ml of blood).

· Cause discomfort and annoyance. Weight loss, loss of condition and reduction in milk production may occur as a result of nervousness and improper nutrition because animals spend less time eating. The wounds and skin irritation produced by these parasites result in discomfort and irritation to the animal.

- External parasites can transmit diseases from sick to healthy animals due to their habit of moving from one host to another. Some of the transmitted diseases are serious with fatal consequences.

- Bites can damage sensitive areas of skin (teats, vagina, eyes, )

- Tick attachment between the claws of the feet may cause severe lamness.

- Cause huge economic losses through skin damage rendering it unsuitable for the leather industry. India used to get the largest foreign currency earnings from the export of skins and hides. This has been deteriorating due to the decrease in skin quality.

- The financial burdens of diagnostic, therapeutic or preventive programs at flock, community and national levels have large financial requirements.

How do we know if an animal is suffering from external parasites?

- Sheep/goats with an irritated skin will be persistently scratching themselves. They will use their teeth, hind hooves and horns (if they are horned). In extreme cases, affected animals will rub on walls of shelters, fence posts and any solid object they can find.

- Remember that most parasitic infections will give rise to a generalised irritation whereas skin diseases will probably be more localised.

- grating teeth, loss of appetite and shaking the head frequently for seemingly no reason is indicative of nose bot fly infestation.

- Lesions consist of foul smelling ulcers resulting from severe fly infestation. The ulcers often have a ‘honey combed’ appearance and are filled with larvae (maggots).

- Decreased feed intake, resulting in decreased weight gains and milk production

- Skin damage, hair loss, Scale formation, thickening and wrinkling

The major external parasites

Sheep and goats can suffer from a range of external parasites; the major ones include ticks, mites, lice, ked, fleas and flies. A short description of each is presented below.

Ticks

Ticks are one of the most serious ectoparasites in India. They cause the greatest economic losses in livestock production. Their effects are various including reduced growth, milk and meat production, damaged hides and skins, transmission of tick-born diseases of various types and predispose animals to secondary attacks from other parasites such as screw worm flies and infection by pathogens such as Dermatophilos congolensis, the causative agent of streptothricosis. Other losses directly attributable to ticks include skin damage that greatly lowers value of the skin. Some of the tick borne parasitic infections in sheep and goats include:

- Babesia ovis: transmitted by Rhipicepalus bursa and Rhipicepalus evertsi;

- Babesia motasi:transmitted by Haemophysalis spp, Dermacentor spp, and Rhipicepalus bursa;

- Theileria ovis: transmitted by Rhipicepalus bursa and Rhipicepalus evertsi;

- Anaplasma ovis: transmitted by Rhipicepalus bursa and Rhipicepalus evertsi;

- Heart water: transmitted by Ambylomma herbarium and Ambylomma variegatumand

- Tick paralysis: transmitted by Ixodes rubicundus , Rhipicepalus evertsi, Ambyloma and Dermacentor.

Different tick species have different locations of attachment. The location can indicate the type of tick. Table 1 shows the sites of attachment of different tick species.

Table 1 Site of tick attachments on animals

| Tick species | Common sites of attachment |

| Haemaphysalis | Ear, limbs, dewlaps, neck, tail, axial, groin and abdomen |

| Boophilus microplus | Ear, limbs, dewlaps, abdomen and chest |

| Boophilus decoloratus | Abdomen, limbs, dewlap and groin |

| Ambylomma variegatum | Under the tail, margin of the anus, limbs and groin |

| Rhipicephalus evertsi | Neck, under the tail and around the anus |

| Hyaloma a. anatolicum | Chest, abdomen, neck, udder and scrotum |

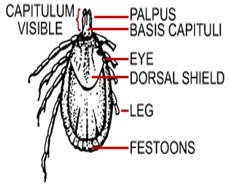

Ticks may be divided into two major groups namely the soft ticks (Argasids) and the hard ticks (Ixodids). Hard ticks can further be divided into three (one host, two host and three host ticks) depending upon the number of hosts involved in their life cycle.

|

|

| Hard tick (Family Ixodidae) | Soft tick |

| Figure 1. Distinguishing features of hard and soft ticks | |

Treatment, prevention and control of ticks

- Acaricide application is the most widely used and effective method of tick control.

- Some ticks can live on the ground for up to 300 days without feeding. In areas where many ticks exist, reinfection of the host occurs continuously and treatment, therefore, must be repeated continuously.

- In subhumid areas the period of highest tick activity is the wet season and only few ticks are found on animals during the dry season. In lowland areas most ticks are active throughout the year and must be controlled

- Be sure to treat all new animals before adding them to the

- Treat with acaricides only where ticks are present in large numbers. Do not use acaricides if tick numbers are not In this case, you can use a needle or thorn to kill them.

- Knapsack spraying is the most practical method if more intensive control measures are needed for a small number of The most efficient method of hand spraying is as follows:

- Spray along the entire length of the back

- Spray the sides and flanks in a zigzag pattern

- Spray the brisket

- Spray each leg

- Spray the belly, udder or scrotum

- Spray the tail and anal area

- Finally spray the head, head, face, neck and ears.

Lice

Infestation of sheep and goats with lice is widespread in most parts of the country. Lice are small wingless insects. The head is broad and flat with mouth parts adapted to chewing. There are two types of lice, the biting lice and the sucking lice.

- Biting lice graze on epidermal tissue, hair and other organic waste. They cause intense itching by their action.

- Sucking lice have a narrow head with mouthparts adapted for penetrating the skin of the host and sucking Both immature and adult stages suck the blood or feed on the skin.

Lice are easily overlooked because of their small size. They can multiply very fast before being discovered. By this time, the animal might be too anaemic and emaciated to recover. Transmission among animals is by way of direct contact. Lice, unlike ticks, have a marked degree of host specificity, even sheep and goats having their own distinct species. Lice can survive away from their host only for a limited period. The whole life cycle is spent on the host’s skin. They are generally transmitted from one animal to another by direct contact. Transmission from flock to flock is usually accomplished by introduction of infested animals to healthy flock. Lice are of minor importance in the transmission of disease.

The saliva and feces of lice contain substances capable of causing allergies giving rise to severe irritations to the skin. This is usually shown by the animal rubbing itself against objects. General unthriftyness, matted, dull fleece with tufts of wool may indicate lice infestation. Animals exhibit reduced weight gain and loss in production. Lameness can result from the foot lice of sheep. Lice are also associated with development of cockle. Cockle is an inflammatory response of the skin to the presence of lice and their saliva. This is seen after the wool or hair has been removed from the skin. Animals in poor body condition are likely to be seriously affected.

Most lice populations on animals vary seasonally, depending on the condition of the host. Lice populations on animals are greater during the rainy months. Animals under stress will usually support larger lice populations than found under normal conditions. Lice do not transmit a serious disease in sheep and goats.

|

|

|

| Louse | Alopecia, crusts, scales and lice. | |

| Figure 2. Lice: Structure and effects on the skin | ||

Diagnosis of lice infestation: If lice infestation is suspected, part the hair and examine the skin carefully. You will see small oval shaped lice moving within the coat, sometimes in clusters. They are dark brown/black in color and move quickly through the coat. Their eggs are oval and cream colored and adhere to the hair follicle. “Droppings” from the lice will be seen as small black specks. If the lice have only recently arrived, the animal will not look too bad but if it has been infested for more than a few days, bare patches will have begun to develop and it will generally be rather miserable and probably beginning to lose weight with all the activity involved in scratching. After two weeks the goat will be in a dire state and in urgent need of treatment, so do not delay! Lice are probably the most common cause or irritation.

Treatment and control of lice infestation: Spraying or dipping with insecticides is effective, but it should always be carried out twice, the first time to kill the lice currently on the body, the second 14 days later to kill lice hatching from eggs present at first treatment. Eggs are not affected by insecticides. If you have more than one goat, then all must be treated or the problem will just keep reoccurring.

Sheep ked

Sheep ked, commonly known as sheep ticks, are adult hairy wingless brown six legged flies about 6 -7 mm long. They are permanent ectoparasite and feed on blood. They transfer from animal to animal through direct contact. Sheep ked can live up to 6 months, during which time the female produces around 10 to 15 young ones every eight days. Reproduction is continuous. Unlike most insects, a female ovulates a single egg that hatches into maggot-like larvae. The maggots are nourished within the body of the female ked until they are fully grown. The mature larva is expelled and glued to the host’s fleece. The larva is whitish, oval, and without legs. The skin turns brown within a few hours after birth and forms a brownish bean shaped pupa that can be found stuck to the wool on the belly, shoulder or thigh.

|

|

|

| Sheep ked | Goat infested with ked scratching the ear | |

| Figure 3. Sheep ked and its effects | ||

An adult ked emerges from the pupa in 2 to 5 weeks, depending on temperature. It crawls over the skin and feeds by sucking blood. This causes irritation followed by scratching, bitting and rubbing against standing objects, fences stones and shrubs which damages the skin and wool. Both male and female keds are blood feeders and feed several times every day. Heavy infestation may, therefore, cause severe anaemia. Skin puncture by blood sucking keds causes an inflammatory response of the skin to the presence of keds and their saliva known as cockles. This is recognized after the wool or hair has been removed from the skin. Cockle causes down grading of the skin because it weakens and discolours it. Keds are mainly seen in colder areas and infestation may be reduced when the animals are moved from cold to hot dry areas.

Ked treatment and control:

- The shearing of woollen sheep greatly reduces the infestation, not only because of the removal of the keds with the wool, but those remaining on the skin are exposed to the environment and this greatly stops their development.

- Spraying or dipping with insecticide after shearing will destroy keds.

Mange Mites

Mites are tiny in size and most difficult to see and identify without the aid of microscope or at least a hand lens. The life cycle of mange mites is similar to ticks with egg, larva, nymph and adult stages. All the stages stay on the animal, feeding on the epidermis, serum, hair, and in some cases, burrowing beneath the epidermis or into hair follicles. A female mite lays up to 16 eggs in her lifetime. Life cycle is completed in about one month. Mites spread from one animal to another mainly through direct contact. Mites do not live very long when removed from the animal. Mites damage leads to skin inflammation and is often accompanied by hair and wool loss. High temperature, humidity and sunlight favour mange mite infestation. Major mange mites may be psoroptic, Sarcoptic or demodectic according to the species of infesting mite.

Psoroptic (Sheep scab)

Psoropts is a highly contagious disease of sheep and goats. Psoropts affecting different animals are highly host specific and a species parasitic on one host will not readily infest a host of a different species. Psoropts mites live on the surface of the skin and are non-borrowing. They pierce the skin and suck the host’s tissue fluids causing irritation, inflammation, discharging lymph fluid that dries to form yellowish crusts and scabs that often protects them.

Psoroptic mange (sheep scab) is the most frequent type in sheep. Sheep scabs can affect sheep of all ages but may be particularly severe in young lambs. It occurs almost exclusively on the tickly wool areas where it produces large scaly, crusted lesions. Intense itching is generally the first sign. When large skin areas are involved, the animals show gradual emaciation and anaemia. The psoroptic mites may be found even in the ear canal (ear mange).

It is located in most areas of the body, such as shoulders, sides and back. Affected skin is covered with exudates. This dries to form a scab. Massive loss of hair usually occurs.

The whole lifecycle is completed in 10-11 days. All stages are capable of survival away from the host for up to 10 days. Optimum conditions for development include moisture and cool temperatures. When conditions are adverse, as in summer, mites survive in protected sites of the body.

Mites are usually more active in winter and the oviposition rate is higher at lower temperatures. In summer the disease progress more slowly, lesions are not obvious and can be missed. Inguinal pouches, scrotum, under tail, ears and skin folds are areas of focus for mites; and serve as hiding places during the dry season; migrate to the general body surface with the onset of cold season.

|

|

|

| Psoroptic Mange. Thick crusts on

bridge of nose |

Psoroptic Mange. Alopecia, erythema,

and thick yellow crusts over thorax |

Sheep affected by Psoroptes scabiei

variety ovis. (Source: Kassa Bayou, 2006). |

| Figure 6. Effects of Psoroptic mange | ||

Sarcoptic mange

Sarcoptic mange is caused by infestation with Sarcoptes scabei variety capri in goats and variety ovis in sheep. It is more common and severe in goats, spreading extensively and in some instances causing deaths. Sarcoptic mange is more acute than the other forms of mange in that it may involve the entire body surface in a short time. It usually starts on a relatively hairless part of the skin and may latter generalize. The complete life cycle may be completed in ten days, although fourteen days is the average period.

The mites burrow the skin and form galleys where they remain for the rest of their lives. They cause small red papules of the skin. The affected area is itchy and frequently damaged by scratching and biting. Loss of hair, thick brown scabs and thickening and wrinkling of surrounding skin is observed.

Sarcoptic mange is highly contagious. The spread is mainly by close physical contact between infected and healthy animals. Sarcoptes are very susceptible to dryness and unable to live more than a few days away from the host.

Demodectic mange (Hair follicle mite):

Demodectic mange invades hair follicles and sebaceous glands of all species of domestic animals. The disease very severe in goats, spreading extensively before it is suspected and in some instances causing death. It causes significant damage to the skin. The disease is severe in goats. It causes the small pinholes in the skin which interfere with its industrial processing and limits its use.

Demodectic mange lesions consist of thick scabs overlaying the skin which was reddened and thickened usually present round the eyelids, nose, the brisket, lower neck, forearm and shoulder and the tips of the ears. In severe cases there may be a general hair loss and thickening of the skin. Animals with severe demodectic mange generally have immune systems that do not function properly.

The disease spreads slowly and transfer of mites takes place by contact. Demodectic mange causes small nodules and pustules which may develop into large abscess. The contents of the pustules are usually white in colour and cheesy in consistency. In large abscesses the pus is more fluid. It causes small nodules and pustules which may develop into larger abscess. There may be a general hair loss and thickening of the skin.

Factors that contribute to the spread of mange mites

Ø Increase in livestock trade

Ø Absence of veterinary regulations for ectoparasite control in the movement of livestock across borders

Ø Poor awareness of farmers and poor level of management

Ø Mange mites can survive outside the host.

Ø They do not cause visible mange in every animal.

Ø Irregular ectoparasite control

Ø Despite acaricide application, possibly development of resistance to acaricides might also contribute

Control and treatment strategy for Mange mites:

- Treatment and control should focus on all animals in a flock to achieve control;

- If spraying, start at the head, finish at the tail, and spray all areas of the body

- There is no acaricide yet which readily destroys the eggs of mange mites; thus a 2nd treatment is necessary after 7days for psoroptic mange and 14 days for sarcoptic mange to get the newly hatching parasites.

- Thick scabs and crusts should be loosened or removed mechanically with a comb before spraying. The animal can be washed with soap and water to soften and remove the epidermal scales.

- Spray animal houses and pasture fences with acaricides

- Animals newly introduced to a flock are the main source of infection. Quarantine newly bought animals and treat twice before they join the herd.

- Dipping is more effective than spraying. Acaricides such as Diazinon 60% or Ivermectin injection (200 mg/kg) are effective.

Fleas

Fleas are small, wingless insects varying from 1.0 to 8.5 mm in length. They are narrow insects compressed on the sides with spines directed backwards.

Most species move about a great deal and remain on the host only when they obtain a blood meal. The legs are well developed and they can jump as far as 7 to 8 inches.The flea under favourable conditions a generation can be completed in as little as 2 to 3 weeks. Mating take place on the host and eggs also lay on the host. Since the eggs are not attached, they drop to the ground and hatch in from 2 days to several weeks. Development occurs most commonly in the bedding of the resting area of the host. The larvae are very small worm like, legless insects with chewing mouth parts. In several weeks they go through 3 larvae stages, feeding on organic debris. The pupa stage lasts approximately one week, and then the newly emerged adult flea is ready to feed on blood within 24 hours.

The stick tight flea is the most common flea on sheep and goats. It attaches firmly to its host usually on the face and ears. This species remains attached to its host for as long as 2 to 3 weeks. During this time, eggs are layed. They drop to the ground and hatch into larvae. Large populations of this flea may cause ulcers on the head and ears. Flea infestations spread to other animals including humans.

Prevention of external parasites

Rather than waiting until the problem of external parasites becomes serious, farmers should maintain a strict preventative regimen to controlling external parasites.

- Conduct a thorough physical evaluation of your sheep and goats at least once weekly. Run your hand over each animal’s hair coat, visually inspecting for excessive hair loss, flakes of loose skin, areas of skin irritation, and any crusty lesions or bumps that might indicate infection with an external parasites.

- Immediately separate and place any animal that shows sign of parasite infection or seems to be unthrifty. This helps to reduce the chances of passing infection on to the rest of your animals. Quarantined animals should not be mixed with the main flock until treatment is complete and the parasite eradicated.

- Isolate newly introduced animals and treat them for external parasites before mixing them with other animals.

- Practice good sanitation habits.

o Clean animal houses regularly.

o Seal with cement or mud all cracks in the floor and walls of livestock housing.

o remove grass/plants around the barn

o All litter and discarded wool must be collected and burnt or deposited out of animal contact.

· Spray housing with an appropriate pesticide every two weeks if possible.

· Farmers should also be aware of ways to reduce the number of ticks on pasture.

o Rotate the land where livestock graze.

- Avoid pasture which has many ticks as long as possible

- Chickens can be kept in places where there are many ticks, for example around watering places,

- Control by good animal hygiene

o Shearing of sheep regularly – for lice and keds

o Shearing and wetting/washing animals regularly with detergents effective especially against lice

· If the above measures are not effective, treat the animals with appropriate pesticide.

Treatment and control of external parasites

- Dipping is very effective; currently, mobile dipping vats for sheep and goats are available.

- Thorough treatment of the infested area is required, especially when ticks infest the ears and under side of the tail or mites infest localized patches on the skin.

- After treating place the animal in the sun to dry.

- Due to the biological cycle of the ectoparasites, a single treatment may not be efficient. The first treatment will only kill the active stages of the parasite present on the animal at the time of treatment. The second treatment will kill any eggs that have hatched since the first treatment.

- All animals introduced to a farm must be treated immediately upon arrival to avoid the spread of new parasites on to the farm.

- If external parasites are seen on an animal, it should be treated immediately to prevent transmission to others.

- Some traditional methods of external parasite control can These include.

- Washing the animal with salt water.

- Smearing the body of the animal with spent oil

- Using repellent herbs

- Using kerosene to rub the predilection sites.

- Use tick grease and/or old engine oil, to reduce parasite numbers on animals. Soaking cloth with a mixture of old engine oil and insecticide and placing it on a tree or on a pole where animals will rub against it will help to apply the material to the

- Once the animals are treated the buildings/ paddocks, barns must be thoroughly cleaned and disinfested with a suitable No sheep should be housed/grazed in the disinfested area for at least 21 days.

- External parasites can develop resistance to acaricides and this is encouraged by frequent dipping and the use of dip solutions at a lower than recommended The manufacturer’s recommendations should be strictly followed.

- Acaricides are toxic to people as well as animals and care should be taken to limit contact with the skin and prevent any possibility of dip fluid being Or contaminating ground water.

- Acaricides are also very damaging to wildlife and fish so great care is needed when discarding used dip fluid.

- Do not recommend unnecessary external parasite This will waste a farmer’s money and increase possibility of development of drug resistance.

- Burning of pasture and raising poultry that can reduce parasite numbers help in external parasite control.

- Effect and incidence of ectoparasites can usually be reduced by improving nutrition, hygiene of animal houses and by occasional spraying or dipping

- Regular removal of moist bedding, hay and manure along with preventing the accumulation of weed heaps, grass cuttings and vegetable refuse is very helpful.

Methods of applying chemicals to livestock

Acaricides may be applied to animals by several methods. The following are the most common methods used.

- Dipping: This is very effective if large numbers of livestock need to be treated. Concrete dipping baths that are stationary or a mobile vat can be used especially for sheep and goats. All body parts have adequate contact with the chemical solution since animals are completely wetted. Mobile dipping vats are recently increasingly used in many parts of the country. The mobile plastic vat overcomes the problem of maintaining the concrete vat. The sheep/goats can quickly be lifted in and out of the mobile dipping Farmers can make a good dip tank using half of an old drum.

Dipping should be done in the early morning, so that animals are not immediately exposed to the hot sun. Dipping is not recommended if heavy rain is expected soon after, as the chemical may be washed off quickly.

Ø Hand Spraying: Hand spraying using knapsack sprayers is the most commonly used method of applying acaricides in Ethiopia. It is effective especially if a small number of animals are to be treated. If a sprayer is not available, then the pesticide can be applied with a paint brush or a cloth or sponge on the end of a stick. During spraying, the animal should be tied securely and the entire animal should be sprayed by following a strict sequence starting at the head and finishing at the tail to cover all areas of the body thoroughly.

- Pour on acaricides: a small volume of a special acaricides is poured along the backline of an animal. It disperses over the body surface to kill the infesting ectoparasites. This is a very effective method of

- Injection: This is a relatively new form of a systemic pesticide such as Ivomac. This is simply injected into the animal. There is a broad spectrum of action against a host of parasites. These compounds are generally more expensive than the other alternatives.

- Impregnated ear tags: Some countries use impregnated ear tags, containing acaricides. These are of increasing importance in fly .

- The decision as to which method of control to use depends on the:

- Size of the flock,

- Age of the animals,

- Status of animals (pregnant or lactating),

- The availability of labor and facilities (handling pens, dip baths, ),

- Weather condition,

- Type of ectoparasite (ticks, lice, keds, mange mites, )

Use of pesticides

A great number of chemicals are widely used to control ectoparasites. Early chemicals included sulphur and arsenic compounds. These were replaced in the 1940s by chemicals such as DDT, Dieldrin and Lindane (chlorinated hydrocarbons) – now known to be very dangerous both to livestock and humans. These are now banned in most countries.

Organophosphorus chemicals such as Malathion and Diazinon were then developed and are still in use, though great care must be taken to avoid any contact with the skin, eyes or mouth.

Another group of chemicals is called Organocarbamates, such as Carbaryl and Baygon. These are not so toxic and are in regular use.

The safest of all chemicals are known as synthetic pyrethroids, such as Fenvalerate and Deltamethrin. These are very effective but also much safer than any of the above chemicals. However, they are also very expensive.

General precautions

Always use the recommended dosages for chemicals. Ask for help if you are not sure. Using too high concentrations will not kill more parasites. Instead, it may kill the animal and make the operator ill. Take the following precautions during application of chemicals:

· Apply pesticides only as directed on the labels. Stop and read all warnings, directions, and precautions carefully before using any pesticide.

· DO NOT spray animals in a confined, non-ventilated area.

· DO NOT dip animals when thirsty or overheated. Water animals well before treatment so they will not drink the vat fluid.

· DO NOT contaminate feed or drinking water.

· DO NOT apply insecticides to sick animals or animals under stress.

· DO NOT apply pesticides to lambs/kids less than 3 months old. Use light applications on lambs 3 to 6 months old.

· DO NOT treat sheep and goats just before slaughtering – check the time interval recommended for the pesticide used.

· Store all pesticides in their original container away from food or feed and out of reach of children and pets

· Wear gloves (or plastic bags) to avoid any contact with the skin.

· Wear protective clothing, goggles and face mask to avoid any chemical splashing into the eyes or mouth. If there is any contact, wash immediately with soap and water.

· Never use cooking pots to mix chemicals.

· DO NOT eat, smoke or drink while handling chemicals

· Take care not to damage the environment. Do not pour into rivers or ponds any unused solution dip contents. Dip contents can be drained into pits. The pits should be at least 150 m away from water sources.

· Clean sprayers immediately after use.

· It is extremely dangerous to reuse an empty acaricide container. The containers should be punctured or crushed. The containers should then be buried in an isolation area at least 50 cm below ground surface.

· Wash yourself and your clothes well with soap and water after treatment is finished.

APPENDIX

APPENDIX Table 1. Types of acaricides commonly used and their target parasites

| Compound | Generic name | Trade name | Target ectoparasites |

| Organophosphates | |||

| Coumaphos | Asuntol | Lice, ticks, mites, horn flies | |

| Trichlorfon | Neguvon, chlorfos | Lice, mites | |

| Diazinon | Neocidol | Ticks, lice, mites, horn flies | |

| Dioxathion | Delnav | Horn flies, lice, mites | |

| Fenthion | Baytex, tiguvon | Horn flies, lice | |

| Malathion | Malathion | Lice, kids, mites | |

| Chlorpyrifos | Dursban 26 E | Lice, horn flies | |

| Chlorinated Hydrocarbons | |||

| CHC | Lindan, BHC,

Hexachloran |

Mites, lice, ticks, flies | |

| Thioden | Endosulfan | Mites, lice, ticks, flies | |

| Carbamates | |||

| Carbaryl | Sevin, Vioxan | Mites, lice, ticks, lice | |

| Promacyl | promicide | Mites, lice, ticks, flies | |

| Pyrethrins & pyrethroids | |||

| Deltamethrin | Cooper | Flies, including tsetse flies | |

| Cypermethrin | Ectopor 020 SA | Ticks, horn and face flies | |

| Avermectins | |||

| Doramectin | Mites, lice | ||

| Ivermectin | Ivermectin | ||

DIPPING, POURING AND SPRAYING IN SHEEP

Dipping

Purpose : To eradicate ectoparasites, cure and prevent spread of sheep scab, ward off attacks by sheep blow-flies, remove waste material and dung from the fleece prior to shearing, thus facilitating production of clean wool.

Time : In India, sheep can be dipped immediately before the post-winter shearing and/or before the post-autumn shearing. In addition, they can be dipped 1-4 weeks after shearing, when the fleece has grown long enough to retain dip solution and also allow cuts and scratches incidental to shearing time to heal.

Dipping chemicals : BHC, Lindane (0.25%), DDT (0.5%), Garathion, Malathion (2.0%), Cimathion, Pyrethrin-arsenic sulphide powder (0.2% arsenic), coal tar-creosote (0.76%), nicotine and tobacco dips (0.1% nicotine, 15 kg tobacco leaves in 500 lit water).

Dipping tanks :-

a) Hand bath : In case of small flocks, a tank of galvanized iron (1.2 x 1.0 x 0.5 m) can be used. Sheep can be lifted one by one into the bath and kept for two minutes. The sheep are removed and placed on a drain board to drain off surplus dip back into the dip tank.

b) Swim bath : In large flocks, the dipping tank can be constructed of metal or concrete. It should be 12 feet long at the top and 6 feet long at the bottom, with a incline for the other 6 feet. The tank should be 2 feet wide at the top, sloping to one foot at the bottom, and it should be 6 feet high. The sheep should be completely immersed in the liquid (including their heads and ears).

Precautions :-

Follow the manufacturer’s instructions thoroughly for preparation of the dip as well as its disposal.

Always water and rest the sheep before dipping to avoid their drinking of dipping solution.

Choose a bright, sunny day (neither too hot nor too cold) so that the treated animals will dry quickly and the insecticide will not be diluted by rain.

Avoid dipping of sheep in advanced stage of pregnancy.

Avoid dipping of sick animals, sheep with wounds, young lambs (less than one month old) and stock being sent for slaughter.

Avoid dipping of rams in breeding season to guard against injury to penis or scalding of thigh.

Keep sheep in the holding pen for at least five to ten minutes so that they drain properly, thus avoiding wastage of dip and resultant pollution of the environment.

Complete each day’s dipping by 4 PM so that the sheep will have some hours to dry before nightfall.

Do not return treated sheep to the shed from which they came until it is completely cleaned.

Pouring

When an individual sheep is affected with scab or badly affected with maggots and has open wounds, dipping is not advisable. In such animals, a small quantity of dip is poured into the fleece along the back, sides and belly to achieve the objectives of dipping.

Spraying

Spraying sheep with a fly repellant insecticide solution over the backs and sides is an effective method of controlling ectoparasites in tropical countries. In developed countries, fly-repellant solution is sprayed in the form of a fine mist through a series of nozzles into a roomy tunnel through which the sheep are forced to pass. However, spraying can be done with the help of a power sprayer or hand sprayer in case of small flocks. Spraying is not as economical or efficient as dipping and is recommended only for young lambs which cannot be dipped.

Purpose

- To remove waste materials and dung from the fleece, prior to shearing.

- To eradicate ectoparasites.

- To prevent spread of “sheep scab”

- To wart off attacks by blowflies resulting in maggots.

- Dipping is done usually twice a year i.e once before shearing and a second time when the fleece has grown long.

Precautions before dipping

- Do not dip ewes in advanced pregnancy to avoid inducing abortion.

- Always offer water before dipping so that sheep will not drink the dip.

- Always rest sheep before dipping.

- Do not dip sick animals.

- Dip about a month after shearing when the there is sufficient dip

- Dipping should preferably be completed before noon.

- Allow sheep in a draining pen for sometimes before turning them out on the pasture.

- Chooses a day is possible when the weather is not too hot.

- Dipping should be done during sunny days.

- Care should be taken to avoid contact of eyes and mouth with the solution·

- After dipping place the animal in the open place for quick drying.

Methods of Dipping

- The hand bath used for small flocks. Each sheep is lifted into the bath and turned over on its back.

- The swim bath: this is used for large flocks of sheep.

- The sheep are allowed to swim through and walk up the ramp into the drying pen.

- Sheep dips: the active agents used are

-

- Sulphur

- Arsenic

- D.D.T. and

- Carbolic acid etc

- The quantity of dip depends upon the length of the fleece.

Pouring

- means pouring a small quantity of dip into parts of the fleece along the back, sides and belly.

Smearing

- An ointment with a basis of tar and grease is smeared over the skin of the sheep to destroy parasites.

Crutching

- Means removing soiled and dung – stained wool by hand shears from the crutch of the sheep (perineal and inguinal regions).

Jetting

- Is a method adopted in foreign countries in which the sheep are made to run through a race or “shedder” in which is fixed a pipe which plays a jet of water into the lower part of the abdomen and the crutch.

DR SHIVASHISH DAS,IVRI

REFERENCE-ON REQUEST.