DOG INBREEDING : CONSEQUENCES & RISKS MITIGATION STRATEGIES

What Is Dog Inbreeding?

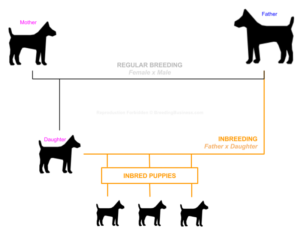

Inbreeding is an act where two relative dogs mate with one another to produce offspring. This tactic was used many times to develop and improve breed bloodline quality. Inbreeding is the mating together of closely related dogs, for example mother/son, father/daughter and sibling/sibling matings. For breeders, it is a useful way of fixing traits in a breed—the pedigrees of some exhibition dogs show that many of their forebears are closely related. For example, there is a famous cat by the name of Fan Tee Cee (shown in the 1960s and 1970s) who has appeared in more and more Siamese pedigrees, sometimes several times in a single pedigree, as breeders were anxious to make their lines more typey. Superb specimens are always much sought-after for stud services or offspring (unless they have already been neutered!), having won the approval of show judges

Understandably, early breed development required some level of inbreeding, although there is no use for it now. The cons considerably outweigh the pros, making this practice inefficient and detrimental.

Inbreeding vs. Linebreeding

Inbreeding constitutes any relative animals mixing together. Linebreeding is a form of inbreeding where dogs might be related distantly, but breeding takes place anyway. This method alleviates some apprehension about inbreeding but can be complexly damaging, too.

Many breeders vehemently defend linebreeding, claiming that all bloodlines are clear. But there is really no way to know when a bad combination of genetics will pop up the more you continue.

Inbreeding and linebreeding in dogs is truly a double-edge sword: it is a very effective tool to produce high-quality specimens in a consistent way, but it also is a surefire way to pass on deleterious alleles. Eventually, a dog may be the perfect specimen for a given breed, but it may also embed several severe medical conditions, and boast a shorter lifespan.

How Genetics Work

If two mates are paired together, both touting desirable traits, they can make excellent quality pups. Even if the two are related, exceptional genes can pass down through the lineage with each litter.

However, where good combinations lie—bad ones do, too. Genetic conditions can essentially be “bred out” of a breed, only to be reintroduced simply by having two copies of the same negative trait.

There are gene mutations called recessive, dominant, and additive. Dominant genes are the ones most commonly seen in litters on a large scale. These genetics are powerful, showing through consistently in each litter.

Additive genes are those where two or more genes give a single component to the puppy’s makeup. So, they meet together harmoniously. And if they don’t, these problems are easier to weed out.

Recessive genes are a bit trickier. Think of recessive genes as ones hanging out on the bench at a game just waiting to be called to the field—it’s a reserve. It’s like having a blue-eyed child born to brown-eyed parents. In the bloodline, the gene is dormant until the right combination hits.

Recessive genes can cause real trouble in terms of inbreeding since they can create two damaged copies of the same gene. An unwanted genetic condition can resurface, congenital disabilities are possible, and other issues can be introduced, too.

So, as you can see, if a puppy is outbred—meaning parents are not related—any imperfect copies of a gene can dissipate quickly. However, if you get two copies of the same bad gene due to inbreeding, the consequences can be dire.

Let’s Get Into the Numbers

Breeders must be diligently aware of purity in bloodlines to avoid genetic mishaps—and inbreeding is a temporary fix to a long-term problem.

Closely related family members pose a much higher risk of receiving two bad copies of a gene. For instance, if a mother gives birth, she passes an even 50% of her genetics to each of her puppies. That means there’s a 50% chance of a bad gene in the mother’s transmitted DNA to each pip.

One of the males in the litter would be at risk of carrying a bad copy. If mother and son are bred, that leaves a 25% chance of unleashing copies of broken genetics to the litter.

Percentages decrease the farther you get down the line, but all it takes is the right combination of genes to create health issues or unfavorable breed standards.

Calculating the Coefficient of Inbreeding

Roll up your sleeves—it’s time for some math. There are a few ways you can calculate the coefficient of inbreeding (COI). The COI involves pinning markers to find the mathematical probability of inbreeding based on the genome.

It takes the likelihood of a pup developing by receiving an allele from both the dam and sire used for breeding. This calculation gives breeders the green or red light when deciding on suitable mates for future litters.

In a desirable COI, you’re looking for numbers beneath 5%. Anything over that threshold is considered high and ill-advisable for pairing.

Problems of Inbreeding

Genetic Health Conditions

When you research breeds, have you ever realized that some are “predisposed” to certain health conditions? For instance, German Shepherds have an increased risk of hip dysplasia, and Golden Retrievers are very prone to cancer.

That is because early inbreeding resulted in pups receiving these recessive genes again and again. Now, we have widespread breed-related problems that worsen as people continue this method.

Genetic Birth Defects

On top of health issues, you also run into potential birth defects. Inbreeding two closely related dogs can cause malfunctioning organs, cosmetic defects, and other abnormalities. While some congenital disabilities are manageable, others pose lifelong trouble for the dog.

Many pedigree dogs born with any flaw are considered defective, so they won’t be eligible for registration. They may only be sold on “pet-only” terms, disqualifying them from breeding or competing.

Birthing Complications

When a mother birthing an inbred litter is passing pups, you may run into trouble. Puppies run the risk of being stillborn, which can greatly impact delivery. If a puppy is upon exit, it can lodge in the pelvis, causing mom to have trouble delivering.

This situation can lead to many potential outcomes, and none of them are good. At best, the mother passes the puppy and the ones behind it live after a bit of trouble. Worst case scenario, you could lose the remaining siblings or the mother during the process.

It might also decrease litter size. This study conducted on Dachshunds describes how inbreeding impacted the size and birth of litters.

Temperament Issues

On top of all else, you run into some serious trouble with undesirable personalities. Puppies that are the product of inbreeding tend to have more nervousness, aggression, and unpredictability than those outbred.

If you’re committing to producing quality dogs, one poor temperament can tarnish your reputation—heaven forbid a child gets bitten in the process.

Decrease in Quality

Once you inbreed dogs too much, you can damage many areas of quality, including lifespan. It can also create weaknesses in genetics, causing unfavorable traits and poor structure.

It can have an impact on fertility, too. Males might produce less powerful semen or potentially be sterile. Females might have trouble getting pregnant, which can have significant implications for your breeding business.

Takeaways

Be careful pairing related, unaltered dogs

If you keep a related pair, make sure one of the dogs is spayed or neutered—at best, fully separated (especially during estrus). You might not recognize the signs of heat until it’s too late.

Inbreeding can cause irreversible issues

Inbreeding causes the overall decline of puppy quality. So, your litters might not be as strong. It might also cause defects in personality and physicality—plus, there’s an increased risk of stillborn pups.

Calculate COI

Calculate COI before selecting a mate for your dam or sire to ensure no potential harmful inbreeding is taking place.

Remember that linebreeding is still inbreeding

Despite any traits you desire to build through breeding, linebreeding isn’t the answer. It’s still considered inbreeding and could impact the success of your litters.

Inbreeding is unethical, and every reputable breeder should reject the concept. Based on COI testing, you can select a mate for your dam or sire that meets the 5% or less rule in pedigree pups—so that takes much of the guessing work out of it for you.

To improve the quality of the breed you love, continuously doing your part to avoid inbreeding is essential.

What Is Inbreeding in Dogs?

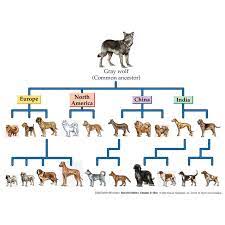

Dog inbreeding is the mating of dogs that are closely related. Examples include the mating of parent and offspring or the mating of siblings. Inbreeding results in individuals with very similar genes. Inbreeding dogs are how individual dog breeds came into being in the first place, and how many bloodlines are perfected.

Modern dog breeds as we use the word today goes back to 19th century England when wealthy people invented the idea of conformation shows and breed standards. With each litter of puppies produced by inbreeding, the characteristic features and appearance of the breed became solidified. A dog with features not in conformity with the breed standard or that exhibited the presence of an unwanted characteristic would be culled for non-breeding purpose. Once the registries came into existence (the Kennel Club and the American Kennel Club being the first), all purebred dogs could trace their ancestry back to the initial founding stock. That is why some commentators will maintain that “purebred dog” and “inbred dog” are synonymous.

DIAGRAM SHOWING INBREEDING IN DOGS (FATHER-TO-DAUGHTER).

Why Do Dog Breeders Use Inbreeding and Linebreeding?

Inbreeding and linebreeding help select the desirable traits in the offspring. Dog breeders use inbreeding to increase the odds of having puppies with desired traits. Many dog breeders want to have a puppy that has the traits in conformity with the breed standards. A dog that meets the breed standards is a dog that has a good chance in the show ring.

Line-breeding is mating the dogs in the same bloodlines. The pedigree of a purebred dog will have the parentage of a dog for as many generations as the record has been kept by the registry. Records of some dogs go back to the late 1800s. Line-breeding uses the pedigrees of dogs to select mating pairs. The sire and the dam will share a common ancestor. For example, a champion show dog may be selected as a stud for a granddaughter. Dog breeders will want to do linebreeding for two primary purposes:

- linebreeding helps breeders pick mates with the characteristics wanted in puppies, and

- pedigrees are more valuable with a number of champions in the bloodline.

Breeders want to produce that perfect dog. With dogs, it is easy to see generations of the same dog at the time because dogs mate repeatedly and produce many offsprings in a lifespan. Dog breeders, in fact, many times own generations of offspring and can know what characteristics are lacking or strong in a particular dog and breed to offset or pass-on this quality to produce better puppies. These puppies then can be marketed to other breeders who are looking to do the same thing.

The other reason a breeder may want to line-breed would be to increase the market value of a litter by giving that litter some good-on-paper heritage. In other words, the more championship dogs that appear in a pedigree the more valuable the dog will at least be on paper. Before the advent of the science of genetics this kind of assumption that the “apple doesn’t fall far from the (championship) tree” would be all a buyer could go on. Still, the truth is that all advertisements for a puppy are likely to state something about the number of championships in the bloodlines. Puppies with five championships in the bloodline can be marketed with higher price tags than puppies with maybe even better breed conformity and even better health but with no such pedigree. Unfortunately, ethical breeding would call into question any breeder with the knowledge now available about genetics breeding dogs using line breeding with solely this profit motive. Dog breeders have many other ways to be profitable so resorting to unwise practices is badly perceived.

What Is the Coefficient of Inbreeding?

The coefficient of inbreeding is a mathematical calculation of probability. It represents the chance that a dog will inherit a homozygous pair of alleles from an ancestor on both sides of the pedigree, or that a given percentage of a dog’s genes will have homozygous genes (i.e. the same genes). A mating of full siblings will result in a COI of 25%; half siblings 12.5%, and first cousins 6.25%. The Kennel Club helps people do their math by providing a calculator for each breed based on its records of pedigree. A breeder need only put in a name or a registered dog and registered dam in order to get the COI.

A dog has 19,000 genes set out in pairs of two. These genes are put together in pairs as strains and form the 39 chromosome pairs of a dog. Many bad diseases and unwanted traits that are not immediately expressed are recessive traits. Recessive traits must have homozygous alleles in order to be expressed. For example, the incurable disease degenerative myelopathy is inherited when a dog inherits from his carrier dam and his carrier sire the recessive genes from each. The coefficient of inbreeding tells a breeder how likely it is that one of these little time bombs will be in a puppy.

The higher the coefficient of inbreeding the higher the chance and the greater the risk for both the puppy and the owner.

On the flipside, the high coefficient of inbreeding also tells a breeder how likely it is that a breeding pair will produce a puppy of a certain color or have a certain height or have a more curly tail. It is literally a double-edged sword.

Most commentators say a coefficient above 10% is too risky in terms of the health of the dog. Higher coefficients will be associated with a diminishing vitality in the dog, smaller litter size, and shorter lifespan (i.e. inbreeding depression).

In order for the coefficient of inbreeding to be a good predictor, it is ideal to have the pedigree of the dog from the founding of the breed. The fewer generations inputted, the lower the coefficient will be and the less useful it will be as a predictor. A good benchmark is to be able to identify pedigree for at least five generations on both sides.

CONSEQUENCES OF DOG INBREEDING

The consequences of inbreeding in dogs are manifold, and for most, they are lethal to dogs affected. The main problem with inbreeding is that the consequences take a while to be seen in a bloodline or a breeder’s breeding program. Indeed, many dogs will suffer later on as senior dogs, while some litters may have a higher ration of stillbirth. It’s difficult to figure it all out and pin it down as being a consequence of inbreeding, but it often is.

- Inbreeding depression

Way before the science of genetics, it was noticed by the livestock breeders that too much inbreeding had a diminishing return in the vitality, fecundity, and mortality of the stock. Today, this phenomenon is called inbreeding depression.

The benefits of inbreeding to acquire specific good traits comes with it a host of traits that make the inbreeding counterproductive for both the breeder and the dog. The reason inbreeding depression happens is because many negative characteristics of a dog (and other animals as well including humans) are expressed only when a dog has two alleles of a gene that are the same (i.e. homozygous). Many bad diseases and traits will only be expressed when there are two copies of recessive genes for the condition. The fatal and incurable disease of degenerative myelopathy is an example. The dog’s genome of 19,000 genes has been mapped, but how each of these individual genes is expressed is still an open question.

Diversity in the genetic makeup of any individual dog or any breed makes a dog and a breed more likely to be stronger, more fertile, and more likely to live a long life.

- Smaller Gene Pool

A smaller gene pool is the necessary consequence of having the great breeds we have today.

Purebred dogs can only be registered as purebred if the sire and dam were also purebred and so on, with all dogs back to the first founding of the breed. Unfortunately, with the small gene pool comes the exacerbation of the deleterious impact of inbreeding depression especially over time.

Purebred registries are not only small gene pools but also most of the time closed gene pools. For example, a puppy must have a sire and dam that are both registered by the Kennel Club in order for it to be Kennel Club registrable. This kind of protectionism, while understandable, keeps the gene pool closed from even the introduction of new blood from other countries that do have very respectable registries and healthy dogs.

Refusal to recognize the pedigrees of dogs from different places means that not only is the gene pool artificially closed by the purebred registry itself, but it is also very limited in its geographic scope. A mutation for a new disease that crops up in a popular sire in London will be passed on to many, many offspring before it may even be discovered. Closed gene pools with circumscribed locales are doomsday scenarios waiting to happen.

- Expression of Deleterious Recessive Alleles

Dogs have over 600 genetic diseases. A cow has a little over 400, a cat over 300, and a goat less than 100. In wild animals, the comparisons become even more shocking. A gray wolf has six genetic disorders, and a coyote only three. The reason for this is because of the closed gene pool and the impact it has had in causing tremendous homozygosity in the genes of dogs.

Dogs frequently will have two copies of an allele that is identical for a trait. Some very bad diseases in dogs are expressed only when a sire that has a recessive gene is mated with a dame that also is a carrier or when a dam is a carrier of an X-linked recessive gene. The impact on the litter of puppies can be tragic.

For example, in the rare disease of Severe Combined Immunodeficiency, a dam will be perfectly healthy but will pass on to fifty percent of her puppies the X gene with the recessive gene for the disease. Male puppies with the recessive gene will be listless (i.e. having or showing little or no interest in anything), have diarrhea, and most likely die. Female puppies will be fine, but fifty percent of them will likely to be carriers, so this goes on and on over dozens of future generations.

A serious cardiac disease in which there are four defects in the heart present is Tetralogy of Fallot and it occurs when a puppy gets one recessive gene from the dam and one from the sire. The disease causes the puppy to suffer from a continual lack of oxygen.

For some diseases, it is possible to genetic test for before mating. Most notably degenerative myelopathy, progressive retinal atrophy, and von Willebrand’s disease have genetic testing available. Currently, there is no commercial genetics test for severe immunodeficiency disease. Other fatal diseases in dogs, especially forms of cancer, are suspected to be genetically inherited but the mechanisms are not yet understood.

- Passing & Fixation of Defects

Inbreeding necessarily results in the passing on of some undesirable traits with the desirable ones. Dogs may be inbred for one characteristic but another is a tag along that gets fixed with it.

There is no magic trick to only pass the good traits, and the leave the bad ones at the gates. Worst, you do not know at the time of the breeding how bad, the bad traits will happen to be in the future generations.

For example, dogs bred to large or giant dogs with large girth, also, have a tendency to develop bloat and die from it than smaller dogs not bred to be oversized. Many of the endearing unique traits in dog breeds today are the result of homozygous recessive alleles being forever paired together in the future generations.

- Shorter Lifespans

Shorter lifespans are one of the elements found in inbreeding depression. Shorter lifespan goes beyond just the risk of anyone dog having a genetic disease that ends its life. In general, inbreeding makes dogs more susceptible to getting sick. The weakening of the immune system (which is wrapped up in an overall loss of vitality) makes it likely that dogs succumb to a host of non-genetic illnesses as well.

Therefore, it is hard to know how strong the relationship is between the inbreeding coefficient of a given dog and its cause of death.

Simply because a high coefficient of inbreeding implies a loss in vitality for the dog, resulting in a weak immune system, making it a potential victim to so many diseases that are not inherited.

- Long-term Structural and Morphological Issues

Poor maligned dog breeders—from reading social media they must really hate dogs. The truth is that it was the zeal and overriding love of the dog that made so many people invest so much in them, to begin with, and create all these breeds that fill so many different roles for people today. Dog lovers hate to see their beloved animals suffer. The plight of the English bulldog is one where there is an intense conflict of love for this delightful unique breed and how much suffering breeding should permit. The damage in the breed’s creation was done over a century ago so to pass a law preventing the breeding of any brachycephalic dogs (and there are people who do want that law) and completely ending the breed in some places (ironically more likely to happen in England than the United States) would be a tremendous loss to many who love it. This topic is for a different article, but safe to say there is a dearth of positive articles on purebred dogs or their breeders.

Other unknown genetic tag-alongs breeders just can’t know because not even the scientists know them. The genetics of a dog is an ongoing investigation. It may be found tomorrow that an extra straight tail on a Dalmatian is somehow genetically linked to the occurrence of hip dysplasia in the breed. These kinds of problems sometimes take human generations to become apparent, but hopefully, it won’t be too late for the given breed and its specimens.

However, inbreeding holds potential problems. The limited gene pool caused by continued inbreeding means that deleterious genes become widespread and the breed loses vigor. Laboratory animal suppliers depend on this to create uniform strains of animal which are immuno-depressed or breed true for a particular disorder, e.g. epilepsy. Such animals are so inbred as to be genetically identical (clones!), a situation normally only seen in identical twins. Similarly, a controlled amount of inbreeding can be used to fix desirable traits in farm livestock, e.g. milk yield, lean/fat ratios, rate of growth, etc.

Natural Occurrenceof Inbreeding

This is not to say that inbreeding does not occur naturally. A wolf pack, which is isolated from other wolf packs, by geographical or other factors, can become very inbred. The effect of any deleterious genes becomes noticeable in later generations as the majority of the offspring inherit these genes. Scientists have discovered that wolves, even if living in different areas, are genetically very similar. Possibly the desolation of their natural habitat has drastically reduced wolf numbers in the past, creating a genetic bottleneck.

In the wolf, the lack of genetic diversity makes them susceptible to disease since they lack the ability to resist certain viruses. Extreme inbreeding affects their reproductive success with small litter sizes and high mortality rates. Some scientists hope that they can develop a more varied gene pool by introducing wolves from other areas into the inbred wolf packs.

Another animal suffering from the effects of inbreeding is the giant panda. As with the wolf, this has led to poor fertility among pandas and high infant mortality rates. As panda populations become more isolated from one another (due to humans blocking the routes which pandas once used to move from one area to another), pandas have greater difficulty in finding a mate with a different mix of genes and breed less successfully.

In cats natural isolation and inbreeding have given rise to domestic breeds such as the Manx which developed on an island so that the gene for taillessness became widespread despite the problems associated with it. Apart from the odd cat jumping ship on the Isle of Man, there was little outcrossing and the effect of inbreeding is reflected in smaller-than-average litter sizes (geneticists believe that more Manx kittens than previously thought are reabsorbed due to genetic abnormality), stillbirths and spinal abnormalities which diligent breeders have worked so hard to eliminate.

Some feral colonies become highly inbred due to being isolated from other cats (e.g. on a remote farm) or because other potential mates in the area have been neutered, removing them from the gene pool. Most cat workers dealing with ferals have encountered some of the effects of inbreeding. Within such colonies there may be a higher than average occurrence of certain traits. Some are not serious, e.g. a predominance of calico pattern cats. Other inherited traits which can be found in greater than average numbers in inbred colonies include polydactyly (the most extreme case reported so far being an American cat with nine toes on each foot), dwarfism (although dwarf female cats can have problems when trying to deliver kittens due to the kittens’ head size), other structural deformities or a predisposition to certain inheritable conditions.

The ultimate result of continued inbreeding is terminal lack of vigor and probable extinction as the gene pool contracts, fertility decreases, abnormalities increase and mortality rates rise.

Selective Breeding

Artificial isolation (selective breeding) produces a similar effect. When creating a new breed from an attractive mutation, the gene pool is initially necessarily small with frequent matings between related dogs. Some breeds which resulted from spontaneous mutation have been fraught with problems such as the Bulldog. Problems such as hip dysplasia and achalasia in the German Shepherd and patella luxation are more common in certain breeds and breeding lines than in others, suggesting that past inbreeding has distributed the faulty genes. Selecting suitable outcrosses can reintroduce healthy genes, which might otherwise be lost, without adversely affecting type.

Zoos engaged in captive breeding programs are aware of this need to outcross their own stock to animals from other collections. Captive populations are at risk from inbreeding since relatively few mates are available to the animals, hence zoos must borrow animals from each other in order to maintain the genetic diversity of offspring.

Inbreeding holds problems for anyone involved in animal husbandry—from canary fanciers to farmers. Attempts to change the appearance of the Pug in attempts to have a flatter face and a rounder head resulted in more C-sections being required and other congenital problems. Some of these breeds are losing their natural ability to give birth without human assistance.

In the dog world, a number of breeds now exhibit hereditary faults due to the overuse of a particularly “typey” stud which was later found to carry a gene detrimental to health. By the time the problems came to light they had already become widespread as the stud had been extensively used to “improve” the breed. In the past some breeds were crossed with dogs from different breeds in order to improve type, but nowadays the emphasis is on preserving breed purity and avoiding mongrels.

Those involved with minority breeds (rare breeds) of livestock face a dilemma as they try to balance purity against the risk of genetic conformity. Enthusiasts preserve minority breeds because their genes may prove useful to farmers in the future, but at the same time the low numbers of the breed involved means that it runs the risk of becoming unhealthily inbred. When trying to bring a breed back from the point of extinction, the introduction of “new blood” through crossing with an unrelated breed is usually a last resort because it can change the very character of the breed being preserved. In livestock, successive generations of progeny must be bred back to a purebred ancestor for six to eight generations before the offspring can be considered purebred themselves.

In the dog fancy, breed purity is equally desirable, but can be taken to ridiculous lengths. Some fancies will not recognize “hybrid” breeds such as the white or Parti-Schnauzer because it produces variants. Breeds which cannot produce some degree of variability among their offspring risk finding themselves in the same predicament as wolves and giant pandas. Such fancies have lost sight of the fact that they are registering “pedigree” dogs, not “pure-bred” dogs, especially since they may recognize breeds which require occasional outcrossing to maintain type!

Implications of Inbreeding for the Dog Breeder

Most dog breeders are well aware of potential pitfalls associated with inbreeding although it is tempting for a novice to continue to use one or two closely related lines in order to preserve or improve type. Breeding to an unrelated line of the same breed (where possible) or outcrossing to another breed (where permissible) can ensure vigor. Despite the risk of importing a few undesirable traits which may take a while to breed out, outcrossing can prevent a breed from stagnating by introducing fresh genes into the gene pool. It is important to outcross to a variety of different dogs considered to be genetically “sound” (do any of their previous offspring exhibit undesirable traits?) and preferably not closely related to each other.

How can you tell if a breed or line is becoming too closely inbred?

One sign is that of reduced fertility in either males or females. Male dogs are known to have a low fertility rate. Small litter sizes and high puppy mortality on a regular basis indicates that the dogs may be becoming too closely related. The loss of a large proportion of dogs to one disease indicates that the dogs are losing/have lost immune system diversity. If 50% of individuals in a breeding program die of a simple infection, there is cause for concern.

Highly inbred dogs also display abnormalities on a regular basis as “bad” genes become more widespread. These abnormalities can be simple undesirable characteristics such as misaligned jaws (poor bite) or more serious deformities. Sometimes a fault can be traced to a single male or female that should be removed from the breeding program even if it does exhibit exceptional type. If its previous progeny are already breeding it’s tempting to think “Pandora’s Box is already open and the damage done so I’ll turn a blind eye.” Ignoring the fault and continuing to breed from the dog will cause the faulty genes to become even more widespread in the breed, causing problems later on if its descendants are bred together.

In cats, one breed that was almost lost because of inbreeding is the American Bobtail. Inexperienced breeders tried to produce a colorpoint bobtailed cat with white boots and white blaze and which bred true for type and color, but only succeeded in producing unhealthy inbred cats with poor temperaments. A later breeder had to outcross the small fine-boned cats she took on, at the same time abandoning the rules governing color and pattern, in order to reproduce the large, robust cats required by the standard and get the breed on a sound genetic footing.

Recommendations from AWBI

The Animal Welfare Board of India has come up with a set of recommendations. These include —

1. Grade the commercial breeding and sale of dogs as a classified commercial activity and all places where this trade is taking place to be notified and registered as shops and establishments under the Municipal Act. Following which, income tax on revenue earned, sales tax and Vat can be added to the sales

2. Checks on the breeding establishments by personnel authorized by the Animal Welfare Board of India and the State Animal Welfare Board will lead to better management and welfare standards of the breeding houses

3. Impose a penalty on all parties involved in the purchase and breeding of dogs from breeders, who do not possess the required licenses from Municipal Corporation and tax authorities

- Make the unethical practice of inbreeding dogs illegal

- Incorporate a clause in the Dog Breeding Rules to limit the number of times a female dog can be used for breeding

- Implement rules and guidelines about how a female dog should be treated after she is beyond her breeding age

- People must be encouraged and advised to purchase dogs from breeders registered with the AWBI

DR. RAMESH KR. UPADHYA, CANINE CONSULTANT & BREEDER,PRAYAGRAJ,UP

REFERENCE-ON REQUEST

https://www.pashudhanpraharee.com/category/environment-livestock/

https://ec.europa.eu/food/system/files/2020-11/aw_platform_plat-conc_guide_dog-breeding.pdf