Enriching Animal Feed with Millet: A Sustainable and Nutritious Approach

Shweta Sharma1, Anjali, Poonam Yadav1, Gyanendra Singh1, V P Maurya1, Vikrant Singh Chouhan1*

ICAR-IVRI, Izzatnagar, Bareilly, Uttar Pradesh, India

*corresponding author:vikrant.chouhan@gmail.com

At its 75th session in March 2021, the United Nations General Assembly declared 2023 to be the International Year of Millets (IYM). The Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) of the United Nations hosted an inauguration event in Rome, Italy, on December 6, 2022, to officially launch the International Year of Millets – 2023. India is first millet grower in the world. It produces 20% of the global output and 80% of the output in Asia. Rajasthan produces the most millet in India as a result of the state’s good climate. The Indian Institute of Millets Research (ICAR-IIMR), located in Rajendranagar (Hyderabad, Telangana, India), is an agricultural research agency that conducts basic and strategic studies on sorghum and other millets.

Prof. Khadar Vali, known as the “Millet Man of India” and a leading authority on nutrition and food, spoke on the significance of millets.

Millets, a diverse genus of small-seeded grasses, are widely cultivated globally as cereal grains or crops for both human and animal consumption. Despite being the least utilized grain, millet holds significant importance as a major crop worldwide. The millet grain is well-suited for food and animal feed applications due to its rich nutrient profile and phenolic compounds that offer health benefits. Millets are naturally gluten-free, exceptionally nutritious, and high in dietary fiber, contributing significantly to overall nutritional value. Compared to wheat and rice, each millet variety boasts three to five times the nutritional content in terms of proteins, minerals, and vitamins. Millets are an excellent source of B vitamins, calcium, iron, potassium, magnesium, and zinc.

Table .1 A Comprehensive Overview of Millet Categories

| MAJOR MILLETS

|

MINOR MILLETS

|

PSEUDO MILLETS |

| Sorghum (Jowar)

|

Little millet (Kutki/Shavan) | Amaranth (Ramdana/ Rajgira) |

| Pearl Millet (Bajra)

|

Proso millet (Chenna/Barri) | Buckwheat (Kuttu)

|

| Finger Millet (Ragi) | Foxtail millet (Kakum) | |

| Kodo millets (Kodon) | ||

| Barnyard millet (Sanwa) |

DIFFERENT TYPES OF MILLETS

1. Finger Millet (Ragi)

Ragi is the popular name for finger millet. In addition to having a healthy amount of iron and other minerals, ragi is a rich source of proteins and essential amino acids and has the highest calcium content of any meal.

2. Foxtail Millet (Kakum/Kangni)

It is said to have originated in Northern China, where it is treasured as a meal that supports digestive and postpartum health. It has a high iron and carbohydrate content and strengthens animal immunity.

3. Sorghum Millet (Jowar)

It is referred known as Jowar locally. Sorghum is extensively farmed and consumed in several Indian states, and rotis made with Jowar are much easier to digest. In addition to having more antioxidants, calories, and macronutrients than conventional Jowar, organic Jowar is rich in iron, protein, and fibre. Sorghum contains 80-85% TDN, 2-3% oil, and about 8-12% protein.

4. Pearl Millet (Bajra)

Since ancient times, the plant known as bajra has been widely cultivated and consumed across Africa and the Indian subcontinent. Iron, fibre, protein, and minerals like calcium and magnesium are all present. The crude protein present in pearl millet is 12-15% and TDN is 70-75%.

5. Buckwheat Millet (Kuttu)

It helps diabetics and decreases blood pressure. It helps maintain a strong cardiovascular system. It is a pseudocereal, which means that even though it isn’t a full grain or a cereal, it is consumed in the same manner.

- Amaranth Millet (Rajgira/Ramdana/Chola)

This millet has a lot of protein and fibre. It’s loaded with vitamins, minerals, and calcium.

- Little Millet (Moraiyo/Kutki/Shavan/Sama)

One other reliable capture crop grown all throughout India is little millet, the smallest member of the millet family. It is abundant in vitamin B and essential minerals including calcium, iron, zinc, and potassium.

8. Barnyard Millet (Sanwa)

Compared to other millets, it boasts one of the highest fibre and iron concentrations and a low carbohydrate count. Additionally, it has a lot of B-complex vitamins. It has substantial amounts of calcium, phosphorus, and dietary fibre, all of which contribute to increase bone density.

9. Broomcorn Millet

Chena is a common ingredient in bird seed mixes that originates in India. In addition to being utilised as cow feed abroad, it is also eaten as a cereal meal throughout Asia and eastern Europe.

10. Kodo Millet

Kodo is particularly high in niacin, folic acid, and other B vitamins as well as other vitamins and minerals. Calcium, iron, potassium, magnesium, and zinc are among the minerals present. It has a lot of lecithin and is excellent for supporting the nervous system.

NUTRITIONAL PROFILE OF MILLETS

They provide a significant contribution to animal diets because of their high energy levels, calcium, iron, zinc, lipids, and high-quality proteins. They are also rich sources of nutritional fibre and vitamins. Resistant starch, soluble and insoluble dietary fibres, minerals, and antioxidants are all very plentiful in pearl millet, according to Ragaee and colleagues (2006). It comprises 92.5% dry matter, 2.1% ash, 2.8% crude fibre, 7.8% crude fat, 13.6% crude protein, and 63.2% starch, according to Ali and colleagues (2003).

Finger millet is also recognised to have a variety of potential health benefits, some of which may be attributable to its polyphenol content, according to Chethan and Malleshi (2007). Its carbohydrate content is 81.5%, protein is 9.8%, crude fibre is 4.3%, and mineral content is 2.7%, which is comparable to other cereals and millets.

Black finger millet has 8.71 mg/g of fatty acids and 8.47 g/g of dry weight protein, according to Glew and associates (2008). Kodo millet and small millet have been discovered to contain the greatest amounts of polyunsaturated fatty acids in the fat, as well as the highest amounts of dietary fibre among cereals (Malleshi and Hadimani 1993; Hegde and Chandra 2005). While the protein content of proso millet (11.6% of dry matter) was found to be comparable to that of wheat, leucine, isoleucine, and methionine were found to be much more plentiful in proso millet grain than in wheat protein.

CARBOHYDRATES

The starch content of several pearl millet grain genotypes ranges from 62.8 to 70.5% and around 71.82 to 81.02%. On the other hand, according to, finger millet has a total carbohydrate content that ranges from 72 to 79.5%. By thickening, gelling, and increasing volume, the starch included in pearl millet can be used to enhance food texture.

PROTEINS

The second crucial component of millet is protein. Compared to 11.5% in barley, 11.1% in maize, and 10.4% in sorghum, pearl millet is thought to have 11.6% protein. Between 5 to 8% of finger millet is protein. In pearl millet, there are more lysine, threonine, methionine, and cysteine. In finger millet, lysine, threonine, and valine are more prevalent.

DIETARY FIBRE

According to, fibre is regarded to be essential for gut health, and moderate consumption of foods high in fibre may result in an improvement in gut health. Dietary fibre content in pearl millet ranges from 8% to 9%. The prevention of diabetes, colon cancer, and heart disease all depend on fibre.

LIPIDS

The estimated fat content of pearl millet is between 5 and 7%, as opposed to 3.21-7.71% in maize. According to, finger millet contains 1% and pearl millet contains 5% lipid, respectively. Fatty acids including palmitic, stearic, and linoleic acids are present in pearl millet in large levels. There are 5.2% total lipids in finger millet. The main fatty acids present in finger millet were discovered to be oleic, palmitic, and linoleic acids.

MACRONUTRIENTS

More minerals, such as calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, manganese, zinc, iron, and copper, are present in pearl millet than in maize. Pearl millet is recognised as a decent source of fat-soluble vitamin E (2 mg/100 g) because of its high oil content. The grain is also considered to be a great source of vitamin A. Calcium content in pearl millet ranges between 45.6 and 48.6 mg/100 g. On the other hand, depending on the genotype, finger millet has a high calcium level that ranges from 162 mg/100 g to 487 mg/100 g. Magnesium levels in finger millet range from 84.71 mg/100 g to 567.45 mg/100 g.

food fibre, dietary supplements, The benefits of phosphorus include promoting wound healing, lowering body cholesterol, treating diabetes, cardiovascular disease, ageing, and metabolic disorders, reducing tumours, etc.

ANTIOXIDANT

Antioxidants are well-known substances that lessen the body’s exposure to free radicals and have anti-inflammatory properties. Millet is a rich source of antioxidants due to its high phenolic component concentration. Finger millet contains phenolic substances like ferulic acid, phytic acid, phenols, phytates, and tannins, as well as dietary fibre and nutraceutical foods that promote wound healing, lower body cholesterol, treat ageing and metabolic disorders, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, reduce tumours, and lower the risk of chronic diseases, among other things.

ANTI-NUTRITIONAL FACTORS

Antinutritional factors are chemicals that, when included in animal feed, decrease the availability of nutrients. It is thought that their presence in pearl and finger millets reduces the bioavailability of minerals, inhibits proteolytic and amylolytic enzymes, and limits the digestion of protein and carbohydrates. Different types of millets contain antinutrients such phytic acid, polyphenols, and tannins, protease inhibitors, oxalates, and phytates. By using various processing techniques, such as dehulling, milling, malting, blanching, parboiling, acid and heat treatments, fermentation, etc., the quantity of these antinutritional substances can be decreased.

HEALTH BENEFITS OF MILLETS

Millets assist the body cleanse and are anti-acidic and gluten-free. Niacin from millet (vitamin B3) can lower cholesterol, lower the risk of breast cancer, lower the risk of type 2 diabetes, lower blood pressure, help prevent cardiac issues, help treat respiratory conditions like asthma, improve the health of the kidney, liver, and immune system, reduce the likelihood of digestive conditions like gastric ulcers or colon cancer, and get rid of issues like bloating, cramps, too much gas, and constipation. Millet works as prebiotic feeding microbes inside of you.

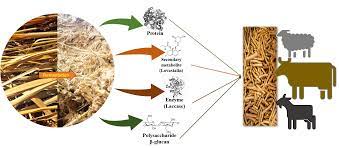

BENEFITS OF MILLETS IN RUMINANT AND POULTRY

Sorghum grass is grown for grazing feed or is green-cut to make silage and hay. Grain sorghum can reduce the amount of maize in grill and layer diets by up to 70% and turkey diets by up to 55% if it is fairly priced. However, it has a lower concentration of the yellow xanthophylls required to colour egg yolks and grill skin. For broilers and egg layers, new varieties of grain sorghum provide a valuable source of protein and energy. Sorghum straw may be successfully consumed by goats as a component of a healthy diet, resulting in daily gains of 66 g.

According to Kochakpadee et al. (2002) and Messman et al. (1991), pearl millet silage may support a 24-26.3 kg/d milk yield in nursing dairy cows at a DM foundation of 36% or 50% in a lucerne silage/concentrate-based diet. If pearl millet is offered to dairy cows while they are nursing, they may need less supplemental protein than is usually provided in their diets. Pearl millet may be used in broiler diets at a minimum of 50% without negatively affecting broiler performance or egg production. Pearl millet can replace up to 15% of the corn in soybean/maize-based diets for laying hens (Garcia et al., 2006).

Ragi straw can be used as fodder in diets for crossbred dairy cows that are supplemented with a well-balanced concentrate mix. Finger millet straw is an advantageous food for growing heifers when used as a supplement to groundnut cake (25%) and wheat bran (25%) (Prasad et al., 1997). The milk production and average fat and solids-not-fat content of the milk both increase by 0.2-0.3% and 1.9 liters/cow/day, respectively, when dairy cows in India are fed with finger millet grain during the early to mid-lactation phase. According to reports, ragi straw helps female goats produce more milk.

Some events are organised on millet all over the world as Curtain Raiser for India-Africa International Millet Conference, 6 July 2023 Nairobi, Kenya and Technical excursion of Agricultural Ministers of G 20 nations to ICAR-Indian Institute of Millets Research, Hyderabad on 17 June 2023 and DG – ICAR unfurls 100-ft-high national flag at –ICAR-IIMR-Hyderabad and A selfie point inaugurated and Mission life style for Environment (life) and millets, Telangana and Sh. Narendra Modi, Hon’ble Prime Minister of India inaugurated the Global Millets (Shree Anna) Conference in New Delhi at Subramaniam Hall, NASC Complex, IARI Campus, PUSA New Delhi on 18 March, 2023 at 11 AM.

In conclusion, millets are a genuine super food that needs to be acknowledged and enjoyed more broadly. They are a valuable crop for small-scale farmers and a rich source of nutrients. They are very adaptable in the kitchen.

REFERENCES

Gopalan C, Rama Sastri BV, Balasubramanian SC. Nutritive value of Indian foods. Hyderabad: National Institute of Nutrition; 2003.

Ullah I, Ali M, Farooqi A. Chemical and Nutritional Properties of Some Maize (Zea mays L) Varieties Grown in NWFP. Pakistan. PJN. 2010;9(11):1113–1117. doi: 10.3923/pjn.2010.1113.1117.

Kunyanga CN, Imungi JK, Velingiri V. Nutritional evaluation of indigenous foods with potential food-based solution to alleviate hunger and malnutrition in Kenya. J Appl Biosci. 2013;67:5277–5288. doi: 10.4314/jab.v67i0.95049.

Ravindran G. Studies on millets: proximate composition, mineral composition, and phytate and oxalate contents. Food Chem. 1991;39(1):99–107. doi: 10.1016/0308-8146(91)90088-6.

Ali MAM, El Tinay AH, Abdalla AH. 2003. Effect of fermentation on the in vitro protein digestibility of pearl millet. Food Chem 80(1):51–4.

Ragaee S, Abdel-Aal EM, Noaman M. 2006. Antioxidant activity and nutrient composition of selected cereals for food use. Food Chem 98(1):32–8.

Chethan S, Malleshi NG. 2007. Finger millet polyphenols: optimization of extraction and the effect of pH on their stability. Food Chem 105(2):862–70.

Glew RS, Chuang LT, Roberts JL, Glew RH. 2008. Amino acid, fatty acid and mineral content of black finger millet (Eleusine coracana) cultivated on the Jos Plateau of Nigeria. Food 2(2):115–8.

Glew RS, Chuang LT, Roberts JL, Glew RH. 2008. Amino acid, fatty acid and mineral content of black finger millet (Eleusine coracana) cultivated on the Jos Plateau of Nigeria. Food 2(2):115–8.

Malleshi NG, Hadimani NA. 1993. Nutritional and technological characteristics of small millets and preparation of value-added products from them. In: Riley KW, Gupta SC, Seetharam A, Mushonga JN, editors. Advances in small millets. New Delhi: Oxford and IBH Publishing Co Pvt. Ltd. p 271–87.

Kalinova J, Moudry J. 2006. Content and quality of protein in proso millet (Panicum miliaceum L.) varieties. Plant Foods Hum Nutr 61:45–9.

Ouattara-Cheik AT, Aly S, Yaya B, Alfred TS. A comparative study on nutritional and technological quality of fourteen cultivars of pearl millets Pennisetum glaucum (L) Leek in Burkina Faso. Pakistan J Nutr. 2006;5(6):512–521. doi: 10.3923/pjn.2006.512.521.

Bhatt A, Singh V, Shrotria PK, Baskheti DC. Coarse grains of Uttaranchal: ensuring sustainable food and nutritional security. Indian Farmer’s Digest. 2003;7:34–38.

Hadimani NA, Muralikrishna G, Tharanathan RN, Malleshi NG. Nature of carbohydrates and proteins in three pearl millet cultivars varying in processing characteristics and kernel texture. J Cereal Sci. 2001;33:17–25. doi: 10.1006/jcrs.2000.0342.

Jha A, Tripathi AD, Alam T, Yadav R. Process optimization for manufacture of pearl millet-based dairy dessert by using response surface methodology (RSM) J Food Sci Technol. 2013;50(2):367–373. doi: 10.1007/s13197-011-0347-7.

Chethan S, Malleshi NG. Finger millet polyphenols: optimization of extraction and the effect of pH on their stability. Food Chem. 2007;105:862–870. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.02.012.

McIntosh GM, Noakes M, Royle PJ, Foster PR. Whole-grain rye and wheat foods and markers of bowel health in overweight middle-aged men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:967–974. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.4.967.

Eshak ES, Iso H, Date C, Kikuchi S, Watanabe Y, Wada Y, Wakai K, Tamakoshi A. Dietary fiber intake is associated with reduced risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease among Japanese men and women. J Nutr. 2010;140:1445–1453. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.122358.

Rooney LW, Miller FR. Variation in the structure and kernel characteristics of sorghum. In: proceeding of the international symposium on sorghum grain quality. iCRISAT. 28–31. Patancheru, India. 1982; 143–162.