HEATSTROKE IN DOGS

Heatstroke is a common problem in pets during the summer months, especially in hot, humid climates. This life-threatening condition can affect dogs of any age, breed, or gender. Heatstroke in dogs is defined as a nonpyrogenic increased body temperature above 104°F (40°C), with a spectrum of systemic signs. The ability to rapidly recognize and begin treatment of heatstroke is vital to maximize the chances of saving the animal’s life.

HYPERTHERMIA

Hyperthermia is an elevation in body temperature that results when heat production exceeds heat loss. Core body temperature rises above the established normal range (99.8-102.8oF/ 37.6-39.3oC) in the homeothermic canine.

- Classifications of Hyperthermia

- Pyrogenic – with fevers, endogenous or exogenous pyrogens (e.g. virus, bacteria, cytokines) act on the hypothalamus to raise body temperature, creating a higher set point. As a normal response acute phase response to infection and inflammation, this rarely raises body temperature higher than 105.5 oF/ 40.8oC, not putting the patient at a severe health risk, and may be beneficial in mitigating morbidity and mortality of infectious diseases.

- Non-pyrogenic – heat stroke, a severe form of heat-induced illness. This results in central nervous dysfunction and multi-systemic tissue injury secondary to a systemic inflammatory response.

Heatstroke is classified as exertional or non-exertional. Exertional heatstroke is typically seen in late spring and early summer, before acclimatization has occurred.

Exertional Heatstroke

Exertional heatstroke occurs during exercise and is more common in dogs that have not been acclimated to their environment. If a period of temperature acclimation is allowed, dogs become less susceptible to heatstroke. Acclimation can take up to 60 days, although the animal is partially acclimated within 10 to 20 days. While exertional heatstroke can occur in working dogs, it is less common because handlers are typically more knowledgeable.

Nonexertional Heatstroke

Nonexertional heatstroke results from exposure to increased environmental temperature in the absence of adequate means of cooling. This may be seen when a dog is enclosed in a parked car or left in a yard without shade and water.

RISK FACTORS

Several Predisposing factors that impair ability to dissipate heat (i.e. via effective panting) or increase heat production further define a patient with heat stroke: anatomy, laryngeal paralysis, obesity, endocrine disease, insufficient water intake, restricted water diet and dehydration. Forced exercise during times of high environmental temperature. More common in brachycephalic breeds (short nosed and flat face), long thick hairy breeds, young ones, aged animals, previously affected animals.

Degrees of Hyperthermia

- Mild – <104 oF / <40 oC does not normally require advanced treatment

- Moderate – 104-106 oF / 40-41 oC

- Severe – >106 oF / >41 oC

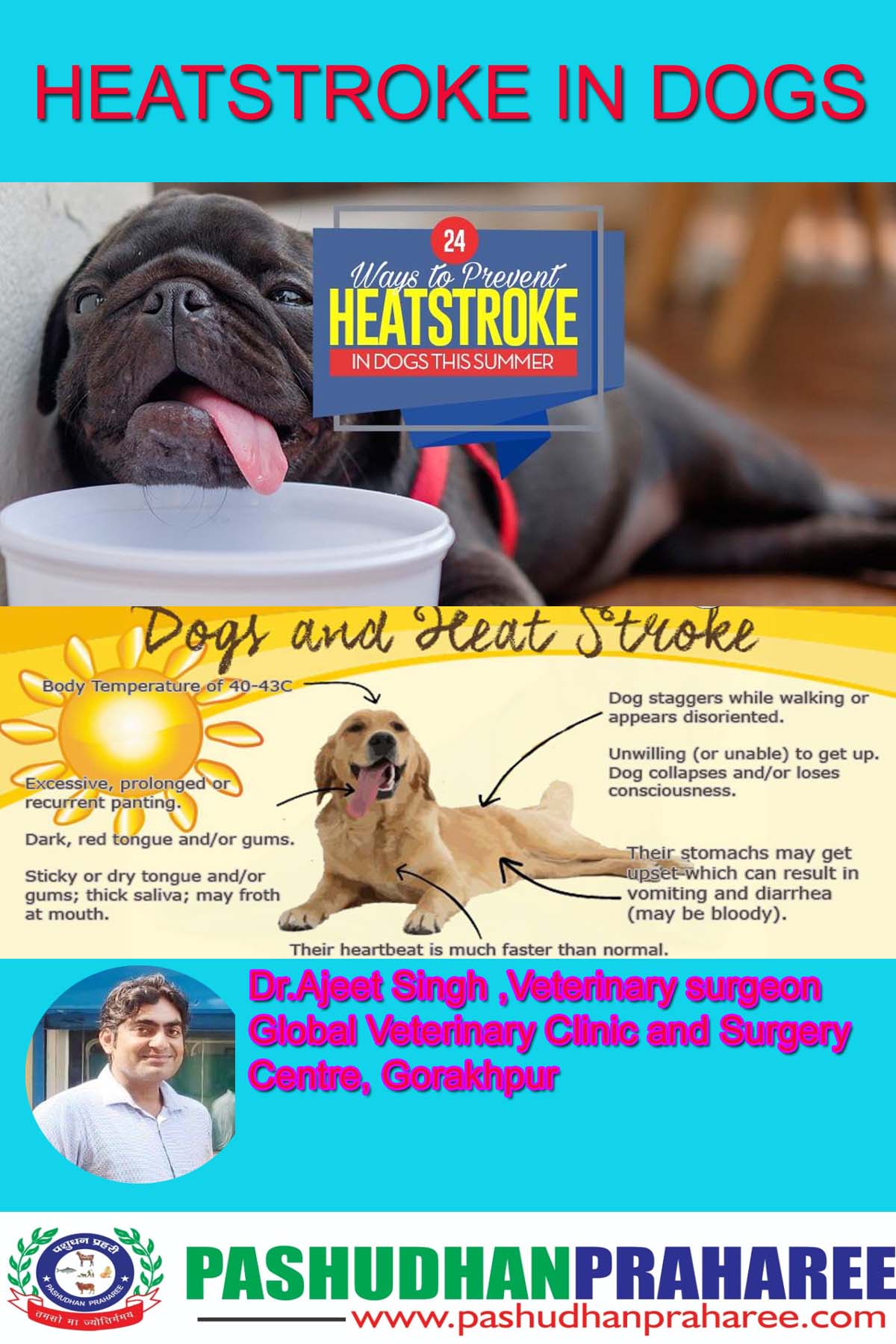

Signs Indicative of Hyperthermia

- Early Stages

- Tachypnea, hyperventilation, panting

- Tachycardia, hyperdynamic femoral pulse

- Hyperemia, dry mucous membranes

- Hypersalivation

- Hematochezia (bloody stool, early sign)

- Altered mentation: depression, stupor, coma

- Dark red mucous membranes

- Seizure (late stage)

- Hypotension

- Weak, collapse

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Hemorrhage

- Cap refill <1 sec

- Severe or Protracted Heatstroke

- Weak femoral pulses

- Pale, gray mucous membranes

- Shallow respirations, progression to apnea

- Vomiting, diarrhea – often bloody

- Seizure, coma

- 3. Delayed Signs – as late as 3-5 days after apparent recovery

- Oliguria

- Seizures

- Icterus

- Cardiac arrhythmias

Diagnosis

- History

- Physical exam findings

- a) Elevated body temperature, however this may be normal depending on intervention before taking temperature and time to transport

- Laboratory

- a) Hemogram – high PCV, anemia later (hemorrhage, hemolysis), thrombocytopenia, leukocytosis

- b) Biochemistry

- Increases: BUN, creatinine, liver/muscle enzymes, Na+, Cl-, K+ (late)

- Decreases: glucose, Ca+, K+ (early), PO4-, Mg++

- c) Urinalysis – proteinuria, hematuria, myoglobinuria, tubular casts

- d) Coagulogram

- Prolonged PT, PTT, ACT

- Elevated FDPs

- Decreased fibrin and platelets

https://www.pashudhanpraharee.com/management-of-heatstroke-in-dogs-3/

Treatments

Initial stabilization should focus on decreasing body temperature to prevent further heat induced injury, maximizing oxygen delivery to tissue by restoring tissue perfusion and arterial oxygen concentration, and minimizing further neurologic injury

- Normalizing Body Temperature

Surface Cooling Techniques – in the field/during transport

- a) Remove animal from the hot environment

- b) Wet down with cool/room temperature water

- c) Place on cool surface

- d) Use fan to blow air over the patient or place before air conditioner

- e) Ice packs may be placed to neck, axillary, and groin areas (large vessel areas: jugular, brachial, and femoral)

Stop cooling methods once body reaches 103-104 oF / 39.4-40 oC as temperature will continue to fall. If hypothermia occurs, patient warming may be necessary.

It is important not to overcool the patient as this could initiate the bodies normal response to hypothermia, shivering. This must be avoided as it will continue to increase the core body temperature by metabolic heat from muscle contractions due to shivering.

- Restoring and Maintaining Tissue Perfusion – treating hypovolemic shock

- a) IV catheter placement

- b) Blood collection for baseline values ideal

- c) Isotonic electrolyte solution @ 20-40 ml/kg bolus; reassess and repeat until cardiovascular parameters normalize. Another fluid guideline alternative is 90 ml/kg/hr, reassess every 15 minutes during administration to adjust rate based on patient response

- d) If blood pressure does not improve with adequate fluid resuscitation, consider drug therapies, but these patients should be at a hospital facility by this time!

(1) Positive inotrope dobutamine 5-10 µg/kg/min

(2) Vasopressor therapy with dopamine 5-20 µg/kg/min

(3) Vasopressor therapy with norepinephrine 0.1-20 µg/kg/min

- e) Colloid bolus (5-10 ml/kg) typically not indicated; pure water loss needs water replacement rather than colloids until DIC does develop; caution if coagulopathy suspected

NOTE: adequate fluid therapy is important, as vasopressors may redistribute blood away from the gut, leading to more severe GIT compromise

- f) Monitor HR (80-120), ECG, CRT (<2 sec), BP (120/80)

- g) Maintenance fluids (40-60 ml/kg/day) plus fluid losses once stabilized (canine should be in hospital by now!)

- Airway and Breathing

- a) Oxygen therapy until respiratory evaluation and oxygen delivery efficiency evaluated

- b) Short term oxygen safe: minimize breathing effort, corrects hypoxemia

- c) Respiratory distress and inability to pant properly contributes to continuing hyperthermia despite cooling measures

- d) If airway patency is compromised, intubation may be needed

- Central Nervous System

- a) Blood glucose (normal 60-110) check immediately in the presence of neurologic abnormalities. If hypoglycemic:

(1) 50% dextrose bolus @ 0.25-0.5 g/kg

(2) Add dextrose to maintenance fluids @ 2.5-5% concentration

- b) Altered mentation after restored tissue perfusion or other signs indicative of cerebral edema (seizures, cranial nerve deficits, paresis, miosis/mydriasis, inappropriate bradycardia, apnea):

(1) Mannitol 0.5-1.0 g/kg over 20 minutes

(2) Hypertonic saline 7% 3-5 ml/kg

(3) Elevate head ~30 degrees

(4) Seizures: Diazepam 0.5 mg/kg IV; phenobarbital 2-10 mg/hr

Additional assessment and treatment, after initial stabilization, focuses on the renal, gastrointestinal, hepatic, and coagulation systems while continuing to monitor cardiovascular, respiratory, and neurologic systems.

- Renal System

- a) BUN, creatinine, and potassium evaluations are paramount

- b) Desired urine output once tissue perfusion is restored and fluid replacements achieved is 2 ml/kg/hr

- Gastrointestinal System

- a) Control vomiting with anti-emetics:

(1) Ondansteron 0.2 mg/kg IV; Dolasetron 0.5 mg/kg IV

- b) Treat gastric ulceration

(1) Famotidine 0.5-1.0 mg/kg; Ranitidine 0.5-2.0 mg/kg

- c) Treat bacterial translocation, +/- sepsis, with broad spectrum antibiotic

(1) Penicillin and fluoroquinolone; Cephalosporin and fluoroquinolone

- Coagulation System

- a) DIC common sequelae: PT, PTT, platelets, FDPs, D-dimers monitored

- b) Fresh frozen plasma may be administered to control hemorrhage

- Hepatic System

- a) Biochemical evaluation of liver enzymes

PROGNOSIS

Prognosis is most dependent on length of time the patient was hyperthermic and highest body temperature experienced. When the body temperature reaches 109.4°F (43°C), marked organ damage and high mortality are seen. Cellular necrosis and destruction of all cellular structures occurs once body temperature has been maintained between 120.2°F to 122°F (49°C–50°C) for only 5 minutes. Probability of survival increases with decreased time period of hyperthermia; however, it is important to monitor the patient for MODS and coagulopathies. Negative indicators of prognosis associated with higher mortality include:

- Development of ventricular arrhythmias

- Severe coagulopathies

- Abnormal neurologic signs that do not resolve once body temperature normalizes.

In humans, 20% of heatstroke victims suffer unresolved brain damage and CNS abnormalities, which have been linked to high mortality rates. Therefore, return of normal CNS function is considered a positive prognostic indicator for dogs that have suffered heatstroke.

PREVENTION

Prevention of heatstroke relies heavily on owner education. Owners can prevent heatstroke several ways:

Ensure availability of adequate shade and drinking water outdoors

- Exercise dogs only during cooler periods of the day.

- Never leave dogs alone in closed vehicles.

- Acclimate dogs to warm temperatures for up to 2 months.

- Surgically address upper airway obstructions, such as brachycephalic airway disease or laryngeal paralysis, to decrease risk in individual susceptible patients.

- https://www.vets-now.com/pet-care-advice/heatstroke-in-dogs/

-