India’s new camel legislation: protection or relegation?

Threatened by trade bans and industrialization, the Raika’s ancient pastoralist culture in Rajasthan is seeking a lifeline in camel milk as it struggles to survive.

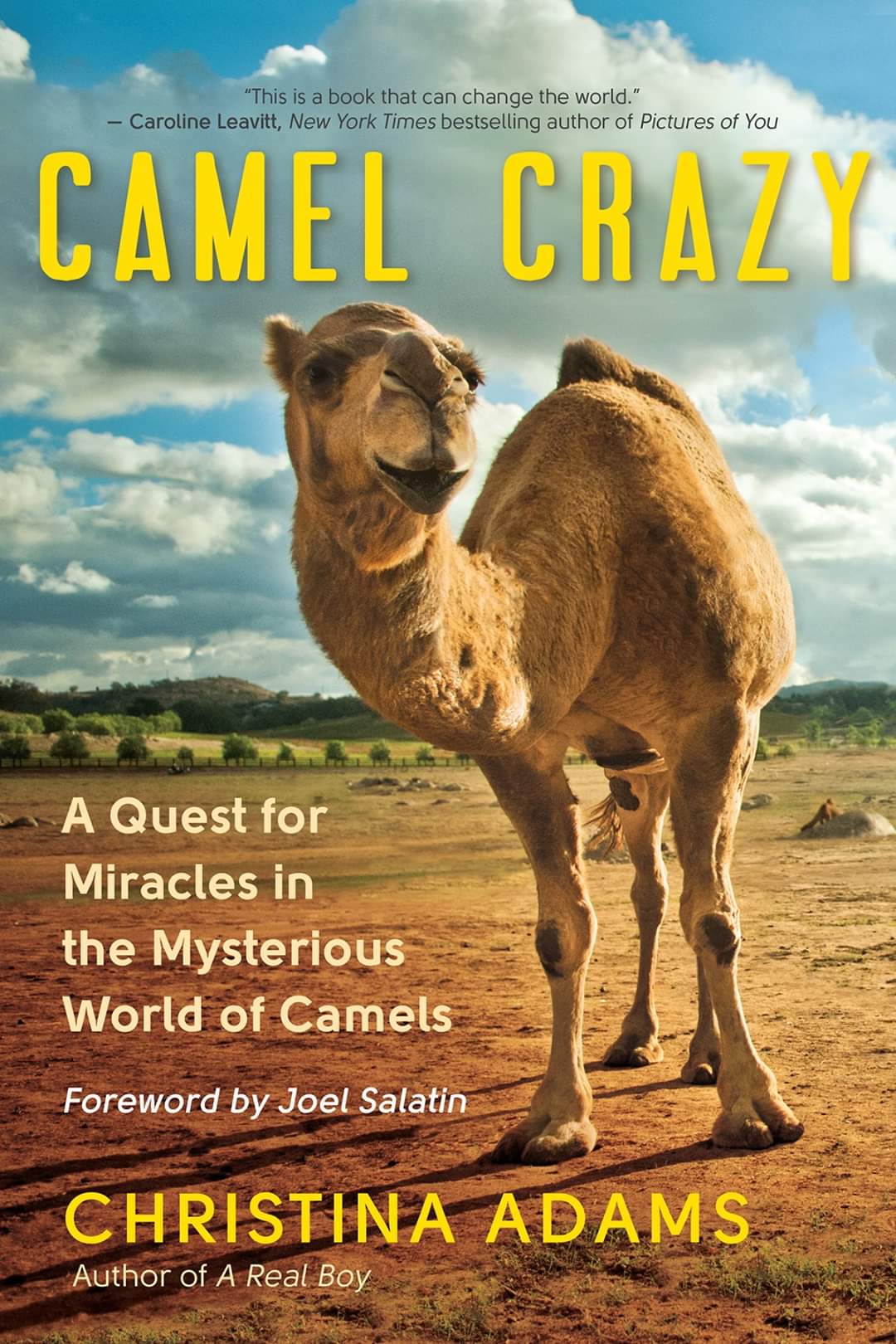

By-Christina Adams

22 June 2016

A Raika leader tasting camel milk ice-cream at Pushkar, Rajasthan. Photo: Camel Charisma

Netha Raika emails photos of himself to the US. The slight twenty five year-old is seeking a match: not for matrimony – he’s a newlywed and recent father himself – but for a defender for his people. From his 70-family village near Bilara in Jodhpur, Rajasthan, Netha sends pictures of the Raika, one of the world’s most treasured camel cultures, to people across the US. Netha’s photos are a kind of lifestyle SOS.

The irony of his dilemma is that just as the Western world is starting to value cultures like the Raika, thanks to emerging data on the medicinal quality of camel milk, they and other Indian pastoralists are caught in a legal bind. The Indian camel milk market is estimated at some Rs. 3024M (around US 45 million), yet India is losing its camels, with only 8,000 pastoralist families now owning the animals.

Classified by the United Nations among the world’s most important agricultural heritage systems, the Raika have identified with camels since the beginning of their collective memory. Roving atop camels half the year, they have traditionally made their living by selling camels and sheep to farmers, sustaining themselves partly with camel milk. The one-humped dromedaries are cultural cornerstones, sources of the camel-hair blankets Raika fathers give to daughters as wedding gifts. But factors such as fewer grazing areas, water diversion to agriculture, and the replacement of camels with farming technology have made camel livelihoods more difficult, accelerating the slump in India’s dwindling camel population. With Raika children now attending school, an opportunity not open to their elders, Netha says ruefully that the young generation has “no interest in camels and sheep.” And although many Raika want to halt the demise by formalising camel milk sales, they are unable to get permits, making their remaining camels near purposele

The bind reached Gordian-knot status when camels were deemed “threatened by the pastoralist community” by the global animal-rights group International Organization for Animal Protection (OIPA). The activists object to almost all camel activities, from transporting them without special vehicles, to their exhibition and use in tourist rides. While the insular Raika were not specifically targeted, a resulting law has now attempted to discourage camel sales outside of Rajasthan, a hub of the pastoralist economy. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) camel expert, Bernard Faye, refutes claims that pastoralists are a threat to their camels, but OIPA, supported by a coalition of people including some strict vegetarian Jains, nonetheless helped initiate the Rajasthan government’s 2014 designation of camels as state animals. Officials said that the move was intended to help check smuggling and migration of the animals, but things weren’t quite that simple.

Anxious Raika herders and their European advocates at first hoped that the law would encourage efforts to sell the precious camel milk, retailing for up to Rs. 3500 (US 52 dollars) per litre in America. However, the ensuing 2015 Rajasthan Camel Bill has stymied almost all India’s estimated 400,000 camels, 80 per cent of which are kept in Rajasthan. The law penalises even the Raika for selling camels for slaughter (which they avoid doing directly) or out of the state, causing a dilemma acknowledged worldwide. “The Raika get conflicting messages from the Indian government. They proclaim camels the state animal but prohibit nomad people to graze in certain areas,” says camel historian Doug Baum. The FAO has meanwhile noted the counterproductive potential of the ban, as the alternative grazing land and necessary support structures like milk sellers’ licenses and insurance have failed to materialise. Likewise, the effects of the law extend to the Raika among India’s 100,000 sheep herders, as covering the distance required by sheep grazing is rendered difficult without camels. As Faye warns, “the actual law in Rajasthan is protecting camels as animals, but not pastoralists as economic actors.” Pointing to camel milk opportunities, he notes that decent pay would make farming feasible. Nonetheless, approval from food and safety authorities remains elusive and state officials unresponsive to Raika petitions.

A largely closed society, the Raika believe their Hindu faith entrusted them as camel caregivers – as Netha notes, “Camels made our God Shiva and his wife.” Long deemed taboo for most commercial uses, camels are largely men’s work, although both men and women live alongside their herds. With a unique memorization of pedigree sheep and camel lineages over eight generations, the Raika have been deemed guardians of agrobiodiversity by the FAO. But with local sales down and no milk permits forthcoming, they are shedding their animals for basic survival income. Although camel sales outside Rajasthan are now labelled smuggling, many animals are bought by out-of-state dealers for resale in expanding Muslim meat markets like Hyderabad and export markets like Bangladesh and Saudi Arabia. This is against Hindu and Raika custom, but Raika sellers see few options – the animals are fast becoming relics.

Only 20 per cent of the Raika now keep camels, a drop reflected in the nine camels left in Netha’s village, where only 4 people under age 30 are sheep herders. Raika youth regard unproductive camels as burdens rather than cherished family members like their elders do. If this trend continues, yet another organic and low-pollution industry may literally turn to dust, driving local communities deeper into unemployment.

So why not start selling milk? “The problem is bureaucracy,” says German vet and camel expert Dr. Ilse Kohler-Rollefson, a long-time advocate of the Raika. Despite demand for the milk and an existing organized collection system in Rajasthan’s eastern and southern districts, Kohler-Rollefson explains that the Rajasthan Dairy Cooperative doesn’t officially accept camel milk, and the Food Safety and Standard Authority of India has not yet set camel milk standards. Extreme seasonal heat, slow trains (risking milk spoilage) and lack of refrigeration compound the difficulties.

Nonetheless, the camel milk market is having some impact, mostly driven by global concerns about autism and diabetes. The milk’s use as an autism treatment gained traction in 2012-2013 with publications in prominent autism and medical journals, and American and Australian camel dairies now cater to the health market. While data is still scarce, anecdotal reports indicate raw camel milk has the most therapeutic benefit, so proper testing and processing is needed. One in every 45 US children is now diagnosed with autism, and parents of the estimated 10 million autistic Indian children are also seeking it in greater numbers. As the milk is increasingly being used in other global products like milk powder, allowing even pasteurized camel milk sales would be a salvation to the Raika. Fathers of autistic children from as far as Chennai even set up a trial supply chain, drawing in the Raika. However, they have ultimately had to turn to imported powdered camel milk due to supply problems – as one father noted after communicating with an Indian government minister to get local milk, “our efforts went to bin.”

Ironically, the Raika themselves are testament to the therapeutic benefits of camel milk, which is thought to lower blood sugar in diabetics, with current research confirming the legendary absence of diabetes among the tribe. However, with camel milk disappearing from their diet and evermore modern lifestyles, diabetes recently appeared among the Raika.

Times have indeed changed for older generations of Raika like Netha’s uncle Tilokram Raika, who has now sold his camels and contents himself with 80 sheep. Nonetheless Netha, who unlike most Raika is literate and has a B.A. degree, wants to hold onto a camel herd he cannot afford. Although the FAO reports that camels are the third fastest-growing livestock animal and offer food security in arid lands, by sad contrast, the Indian camel population plummets as financial necessity forces them to be sold for meat. Still, “We get calls every day from Raika people asking us to buy their milk,” says Kohler-Rollefson.

There are models for success, including pilot schemes for individual collection and marketing that have been sponsored by some local NGOs to ship frozen camel milk to autism and diabetes patients in India, as well as to make cheese. Paying up to Rs 50 per litre to local Raika herders, such projects have enabled some Raika families to retain their camels, or even invest in new ones.

Netha is meanwhile making headway by selling crafted camel decorations and planning a camel-themed retreat to bring American tourists to his village. But his anguish for his people remains. For him, the problem is also personal as well as political. Greater visibility for the Raika may boost the education and marriage prospects of his baby girl – but only if this can be realised before camels are let go and the irreplaceable knowledge of a desert culture is lost.