LEFT DISPLACED ABOMASUM (LDA) IN DAIRY CATTLE

Post no-554 Dt-03/02/2018 Compiled & shared by-DR RAJESH KUMAR SINGH, JAMSHEDPUR, 9431309542,rajeshsinghvet@gmail.com

Other Names –Abomasal Volvulus, Displaced Abomasum, LDA, Left Displaced Abomasum, RDA, Right Displaced Abomasum

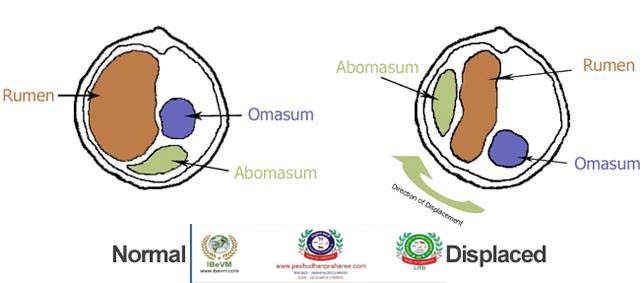

The abomasum is the 4th, or ‘true’ stomach of the cow. It usually lies low near the floor of the abdomen. Displacement is when the abomasum is shifted from its normal anatomical location, to either left (LDA) or right (RDA). Usually atony (lack of stomach tone or contractions) and gas production cause the change. Left displaced abomasum is more likely with 80-90% of displacements being LDA. It is most common in large breed dairy cattle, but theoretically may occur in any bovine. Right displaced abomasum is less common and more serious – as well as moving up the right side of the cow, the abomasum may also rotate on itself causing a life threatening toxaemia. Both displacements will affect the flow of digesta (food) leading to various clinical signs noted later.

Cows in early lactation are at greatest risk of a displacement, with most LDA cows seen in the 2-6 week period after calving. 50-80% are diagnosed within 2 weeks, 80-90% within 1 month. LDA cattle will often refuse to eat concentrates, but still pick at forage and grass. Concurrent disorders are common – ketosis, RFM, mastitis, metritis, milk fever and lameness issues are all increased risks for LDA. These cows are generally affected over the course of a few days. Milk drop is a feature, but the condition may wax and wane for a short period as the LDA can change in size and degree of displacement. Primary Ketosis is a risk factor for displacement development, but secondary Ketosis is always seen with a displacement.

RDA cattle are more acutely sick. They usually go straight off milk and feed, and may not have had other health issues. When the abomasum twists, the cow will become toxic and soon die. A straightforward RDA is a candidate for surgery with a good chance of success. A twisted RDA and the sickness it brings is more complicated to treat, and carries a far higher chance of failure. For this reason, an RDA should really be classed as an emergency and treated as such.

Rearrangement of abdominal viscera in pregnancy is thought to be an important aetiological factor, however reduced abomasal motility is thought to be the primary aetiological cause. Once the abomasum is displaced gas production by the organ continues causing distension and further displacement.

Signalment

A disease of the cow affecting mainly high yielding dairy cows on high concentrate diets. Left displacements usually occur in the first 6 weeks of lactation, although this association is less strong for right-sided displacements and cases of abomasal volvulus. Sometimes displacement does occur before calving, this is in late gestation and accounts for 5% of cases.

Diagnosis

An LDA/RDA is easily diagnosed by vet. They will flick the side of the cow whilst listening with a stethoscope. An LDA/RDA gives a characteristic pinging noise due to the gas trapped in the displaced abomasum. The vet may also push their fist into the cows abdomen whilst listening to hear a splashing (tinkle) noise caused by the fluid trapped in the abomasum.

Diagnosis is made on history and clinical signs in combination with auscultation findings. Using a stethoscope the entire left and right flank should be percussed. Over the region of displacement a distinct ping will be heard. Once a ping is identified the stethoscope should be held over that area whist balloting the lower flank, this creates a splashing sound at the gas fluid interface which is heard as a tinkle. This confirms the presence of a displaced abomasum.

History and Clinical Signs

A typical history would be a recently calved cow with a sudden drop in appetite and milk production. Animals display general malaise and abdominal pain. On clinical exam a rapid loss of condition may be evident, ketosis or decreased ruminal activity on ausculatation. Often the left ribs appear ‘sprung’, with a concave left paralumbar fossa, and the temperature may be normal or raised.

What causes displaced abomasum?

Two main causes of the condition have been identified:

• calving: the majority of cases occur soon after calving. During pregnancy the uterus displaces the abomasum so that after calving the absomasum has to move back to its normal position, increasing the risk of displacement.

• atony (lack of normal muscle tone) of the abomasum: if the abomasum stops contracting and turning over its contents, accumulations of gas will occur and the absomasum will tend to move up the abdomen.

What are the clinical signs?

• inappetance, milk yield drop and reduced rumination are the most common signs.

• there can be diarrhoea, mild colic and a distended abdomen.

• if torsion (twisting) occurs – a problem more common in Right Displaced Abomasum – shock, low temperature and a high heart rate will occur.

• Normally – just like ketosis – ketones will be present in blood, milk, breath and urine.

The clinical signs can be highly variable and range from mild to more severe. Signs may include the following but not all signs are present in every case:

• decreased or absent appetite

• reduced or absent rumination

• decrease in milk yield

• lowered body condition

• small amounts of diarrhoea

• increased heart rate

• similar to acetonaemia, due to reduction in feed intake leading to a similar clinical scenario

• ‘ping’ (high pitched resonant sound) upon flicking the abdomen while listening with a stethoscope

Pathogenesis

There are two manifestations of abomasal displacemet. In both the abomasum becomes trapped between rumen and abdominal wall. The more common presentation is the left displacement (LDA) which is ventral and to the left of the rumen. The omasum, reticulum and liver are also displaced.

Abomasal atony and increased gas production leads to displacement. Factors reducing abomasal motility include a high concentrate diet, increased volatile fatty acids from the rumen, increased Non-Esterified Fatty Acids from body fat mobilisation, hypokalaemia[1], hyperinsulinaemia [2][3] and periparturient disease e.g ketosis, hypocalcaemia and metritis. There are also genetic differences in mediators of abomasal motility [4]Displacement to the left results in a reduced flow of ingesta as well as reduced digestion resulting in anorexia and dehydration.

A displacement to the right (RDA) is less common. Decreased abomasal motility, distension and displacement occurs as in the LDA. Rotation of the abomasum on its mesenteric axis leads to volvulus and constriction of blood vessels and trauma to the vagus nerve resulting in abomasal distenstion with blood-stained fluid and gas, congested mucosa and necrosis of the abomasum, dehydration and circulatory collapse. Additionally the abomasum may rupture, causing peritonitis, shock and death.

Laboratory Tests

Often a severe ketosis is present resulting in raised blood beta-hydroxybutyrate.

If electrolyte levels and blood gas are measured affected animals develop a hypochloraemia and metabolic alkalosis due to reduced outflow of ingesta from the abomasum combined with continued secretion of hydrochloric acid into the abomasum.

Hypokalaemia also develops due to alkalosis (or hyperinsulinaemia in certain cases), which drives potassium into cells combined with a reduced intake due to anorexia.

Treatment

Treatment Options

Conservative methods

• non-surgical management of LDAs has variable success rates

• casting the cow is the main non-surgical option – the cow is cast onto its right side and rolled to try and move the abomasum back into position

• the cow should be re-examined 2 days later, as recurrence rate is high (up to 75%) and a chronically displaced LDA can cause secondary problems such as ulceration, reduced milk yield and adhesions in the abdominal cavity

• toggles (suture material with plastic pieces at the end to form an H-shape) can be used to keep the abomasum in place – one end of the toggle is inserted into the abomasum through a large needle-type device to provide an anchor point for the abomasum to prevent it becoming displaced again

• toggles reduce the rate of recurrence of LDAs, but have variable success rates

Surgical methods

• involves incising into the abdominal wall to locate the abomasum and stitch it to the body wall muscles to prevent it from displacing again

• various techniques to choose from, so the incision may be made on the left flank, right flank or in the middle (ventral midline) – this is largely personal preference of the vet as none of the methods has been shown to be significantly more effective than the others

A number of surgical techniques are documented to correct the displacement. These include:

• Blind toggle abomasopexy

Toggles are useful in low value animals as it is a cheap and fast technique. The animal is cast and rolled onto her back. Two toggles are inserted through the ventral abdominal wall into the abomasal lumen. Once positioned the two toggles are tied together. Following this blind suture it is possible to toggle the incorrect area (e.g. rumen, reticulum) resulting in fatal complications. To avoid this complication a pH strip can be used to confirm the correct location following cannulation before the toggles are put in place

• Right flank (pyloro-)omentopexy

The right flank is incised one hands distance behind the last rib and the displaced abomasum is located. The organ is then deflated and repositioned in the correct location. The omentum (+/- pylorus) is sutured to the abdominal wall and the incision is closed in a routine manor.

• Left flank abomasopexy/”Utrecht”

The left flank is incised just caudal to the last rib and the omentum adjacent to the abomasum is located. A continuous, partial thickness nylon or absorbable suture line with long tails is placed in the body of the abomasum then both ends are passed through separate points on the ventral body wall. An assistant can help locate the correct position for the suture to be passed by palpating the region with a pair of artery forceps. The two pieces of suture are tied externally and hold the abomasum in the correct position whilst adhesions form.

• Right paramedian abomasopexy

For this technique the cow is sedated and cast onto her back. An incision is made to the right of midline caudal to the most posterior part of the sternum. The abomasum is located, repositioned and sutured to the body wall.

• Laparoscopic techniques

It is important for all surgical techniques that post-operatively the cow is given a large amount of roughage and concentrates are introduced into the diet slowly.

1. Roll the cow – The cow is rolled around the abomasum. The gas trapped in the abomasum makes it float to the highest point of the cow so, with a bit of encouragement, it can be floated back into position by rolling the cow. There is a high risk of the abomasum re-displacing if the cow does not fill her rumen up quickly as the space will still be there for it to move into.

2. Toggle – As with rolling the cow, the abomasum is encouraged to move up to its normal position and then with the cow on her back a large bore needle is inserted into the abomasum twice and 2 toggles are introduced and tied on the outside. This should anchor the abomasum in place. This is often a quicker and cheaper option although there is a risk of not toggling the right organ as it is performed blindly.

3. Operate – Several methods are available to operate – all are as good as each other and the one your vet will use comes down to their personal preference. Essentially all methods ensure the abomasum is back in position before anchoring it into place hopefully reducing the risk of a reoccurrence next year. Cows usually recover well but there is the risk of post surgical complications as with any surgical procedure.

4. Cull – Some cows are just beyond hope. Your vet will be able to advise if it makes more sense both economically and for the welfare of the cow to cull the animal.

Prevention

On farms with a high incidence of LDAs or RDAs it is likely that there is a problem with the diet of cows in early lactation and this should be addressed. Overall cases can be reduced by maintaining adequate roughage intake, avoiding a rapid decrease in rumen volume following calving, preventing rapid dietary changes and postparturient illness (hypocalcaemia, ketosis, metritis).

Prognosis

Following surgical correction of an uncomplicated displacement, short term success rates can reach 95%. Abomasomal volvulus and the presence of an abomasal ulcer are associated with a much poorer prognosis. Additionally tachycardia, decreased temperature, black faeces and a long period of illness are all associated with poorer outcomes.

Longer term survival after correction of Left Displaced Abomasums is poorer, with 79% and 73% of animals surviving beyond 2 months for a blind toggle and a paramedian abomasopexy respectively in one study, although the difference between procedures was not significant[11]. The most likely reasons for the slightly poorer long-term survival after LDAs are mastitis, lameness, poor production and infertility.

The abomasum (or true stomach) which normally lies on the floor of the abdomen, is said to be displaced when it fills with gas and rises to the top of the abdomen. It is more likely to be displaced to the left (LDA) than the right (RDA).

Prevention & control of the condition

Of the two causes above, only atony of the abdomen is preventable:

• ensure cattle are not too fat at calving

• feed high quality feeds, with good quality forage

• feed a total mixed ration as opposed to concentrates

• ensure plenty of space at feeding sites

• minimise changes between late dry and early lactation ration

• prevent and promptly treat diseases such as milk fever, metritis, toxic mastitis and retained fetal membranes which reduce feed intake

• maximise cow comfort, minimise stress

• Provision of adequate long fibre in dry cow diet (preferably hay)

• Provision of an adequate supply of palatable energy-rich carbohydrates in the diet, particularly immediately after calving

• Provision of adequate daily exercise for dry cows

• Gradual introduction of concentrates in the dry cow diet prior to calving (up to 2 kg /cow) but avoidance of “steaming up”

• Limited amount of maize silage to dry cows

• Avoidance of “peaking” the milk production in early lactation by increasing concentrate intake

• Prevention of hypocalcaemia and ketosis in the periparturient period

• Achieving the optimum body condition score at dry-off (2.5/5) and calving (2.5-3/5), to minimise condition score loss in the periparturient period to a maximum of 0.5 score (1-5 score).

REFERENCE-ON REQUEST