LUMPY SKIN DISEASE

Aditya Kumar1, Simran jeet Singh2, Niddhi Arora3 and Megha Joshi3

¹Ph.D Scholar, Department of Veterinary Medicine

2PG Scholar, Department of Veterinary Medicine

3Professor, Department of Veterinary Medicine

3UG Scholar

College of Veterinary and Animal Sciences

G.B. Pant University of Agriculture and Technology, Pantnagar, Uttarakhand, India- 263145

Corresponding author mail- simranjeets140@gmail.com

Introduction

Lumpy Skin Disease is an acute, highly infectious disease that is caused by the Lumpy Skin Disease Virus (LSDV) of the Poxviridae family and Capri pox genus (Neethling virus). This disease is also known as, bovine modular oedema, Neethling Virus Disease and Pseudo-urticaria. It is a disease of the bovine family which includes cattle and water buffaloes. It Is believed that the disease originated in Zambia Africa. It is a transboundary infection with high morbidity and low mortality rates. This disease is characterised by the rapid development of cutaneous nodules all over the body, together with lymphadenitis and superficial lymphangitis becoming more common.

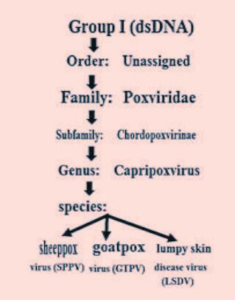

Etiology

Source: Al-Salihi, K. (2014). Lumpy skin disease: Review of literature. Mirror of research in veterinary sciences and animals, 3(3), 6-23.

The disease is caused by the Lumpy skin disease virus also known as the Neethling virus, which belongs to the Poxviridae family. A group of viruses that causes disease in animals other than dogs is contained within the family. The family consist of two subfamilies: Chordopoxvirinae and Entomopoxvirinae. Chordopoxvirinae consist of 10 genera including Capripoxvirus (a double-stranded DNA virus) which further consists of 3 species Sheep Pox Virus, Goat Pox Virus, and Lumpy Skin Disease Virus. LSDV genes exhibit significant collinearity and amino acid similarity, with genes found in other recognized mammalian poxviruses, notably suipoxvirus, yatapoxvirus, and leporipoxviruses.

Epidemiology

According to the World Animal Health Organisation (OIE), LSD is a notifiable disease which has been reported for the first time in Zambia, Africa back in 1929. Either epidemic or sporadic cases of this disease have occurred. In the rainy summer weather, there is an increased incidence of this illness, and the disease is widespread on the water course or low ground. The disease has once been endemic in the African continent, but several outbreaks have occurred periodically outside Africa such as in Madagascar (1929), Israel (1989), Kuwait 1991, the United Arab Emirates (2000), Bahrain (2003), Oman (2009), Bangladesh (2019), India (2019), China (2019, 2020), Nepal (2020), Sri Lanka(2020), Vietnam (2020), Bhutan(2020), Myanmar(2020), Thailand (2021), Malaysia (2021) Laos (2021) and Cambodia(2021). In Asia, the disease has grown so strong that it poses a challenge to Asian livestock management and threatens food security. India observed its first LSD outbreak in the year 2019 in Odisha with a 7.1% morbidity rate and no mortality rate. The recent 2022 outbreak spread across 15 states and affected over 2 million animals with a drop in milk production by 26% in these states. A total of 1 lakh deaths were also observed.

(Source: OIE WAHID and EMPRES-i, 2017)

HOST

The LDS virus exhibits a restricted host range, impacting solely cattle and buffalo. The morbidity rate is higher in cattle compared to buffalo. African buffaloes are regarded as the maintenance host, given that the disease is transmitted by ticks.

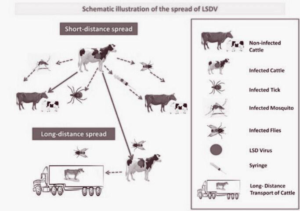

TRANSMISSION

The primary transmission of the LSD virus occurs through Arthropod vectors, including biting flies, mosquitoes, and specific ticks such as Rhipicephalus appendiculatus and Ambylomma hebraem. Calves contract the infection while suckling milk from their dams, and the disease can also spread through natural mating or Artificial Insemination.

Source: Tuppurainen, E., Alexandrov, T. and Beltrán-Alcrudo, D. 2017. Lumpy skin disease

field manual – A manual for veterinarians.FAO Animal Production and Health Manual No.

- Rome. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

SOURCE OF INFECTION

The virus persists in various sources such as saliva, nasal discharge, ocular discharge, semen from infected bulls, milk from infected dams, and skin nodules found in the teats. Even after 33 days of infection, the virus lingers in these skin nodules.

Clinical Signs & Symptoms

Skin lesions covering the entire body

Source: https://atariz1.icar.gov.in/pdf

- Characteristic symptoms of this disease include nodular skin or skin lesions, but the manifestations of this ailment go beyond the mere formation of skin nodules.

- Soft blister-like nodules varying in size from 10 to 50 mm in diameter appear on the body approximately 48 hours after the onset of a febrile condition. With appropriate treatment, the infected animal typically takes about a week to recover. Predilection sites for these nodules are the skin of the head, neck, perineum, genitalia, udder, and limbs.

Lesion on the head and neck

Source: https://atariz1.icar.gov.in/pdf

- Enlarged lymph nodes, notably the sub-scapular and pre-femoral nodes, are easily palpable.

- Initially, signs include tearing, nasal and ocular discharge, and increased salivation.

- Mucopurulent discharges emerge from the nostrils, accompanied by continuous drooling, coughing, and frequently noisy and distressed breathing when the larynx and trachea are affected.

- The limbs undergo significant swelling, enlarging to several times their usual size because of inflammation, oedema, and extensive necrotic lesions and are accompanied by a prolonged high fever (>104ºF) for about a week.

- In severe instances, blindness may result from ulcerative lesions on the cornea in either one or both eyes.

- There is a significant decrease in milk production.

Lesions on the udder and teat

Source: https://atariz1.icar.gov.in/pdf

- The typical sequel of LSD is pneumonia, linked to a sizable grey consolidation area ranging from 20 to 30 mm, with the potential for fatality.

- As time progresses, certain nodules rupture, resembling deep wounds in the skin. The lesion that has sloughed away might result in a hole spanning the entire thickness of the skin, displaying a distinctive “inverted conical zone” of necrosis commonly referred to as “sit fast.”

Raised and separated narrow ring of haemorrhage” (A), skin lesions leaving ulcer (B) and“sit fast” like “inverted conical zone” of necrosis (C)

Source: Mulatu, E., & Feyisa, A. (2018). Review: Lumpy skin disease. J. Vet. Sci. Technol, 9(535), 1-8.

- Infected bulls also experience testicular swelling and orchitis.

- After developing lesions in reproductive organs, bulls and cows may experience temporary or permanent infertility.

Pathological Findings

GROSS PATHOLOGICAL FINDING:

- Raised, circular skin nodules that are firm and uniform in size, possibly merging to form large, irregular plaques.

- Nodules may show a reddish-grey cut surface with serous fluid and subcutis oedema. Resolved lesions, called “sit fasts” or seclude, may potentially form deep ulcers.

- The regional lymph nodes are significantly enlarged, reaching 3-5 times their normal size, exhibiting oedema, and containing pyemic foci, along with concurrent local cellulitis.

- Nodular lesions in muscle tissue and the fascia covering limb muscles may appear grey white, surrounded by red inflammatory tissue.

HISTOPATHOLOGICAL FINDINGS:

- During the acute phase of the illness, it is predominantly marked by vasculitis lesions, thrombosis, infarction, and perivascular fibroplasia.

- Inflammatory cells infiltrate the infected region, and intracytoplasmic eosinophilic inclusions are observed in keratinocytes, macrophages, endothelial cells, and pericytes. Edema and infiltration by epithelioid cells occur in the epidermis and dermis.

- Blood vessels in the dermis and subcutis show endothelial proliferation in the dermis and subcutis, leading to lymphocytic cuffing, thrombosis, and necrosis. Intracytoplasmic inclusions, mainly eosinophilic purple, appear in various epithelial elements, sebaceous glands, and follicular epithelium, often with a clear halo, likely due to processing artefacts.

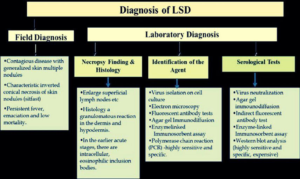

Diagnosis

Sources: K. A. Al-Salahi, (2014). Lumpy Skin disease: Review of literature. MRSVA. 3 (3), 6-23

Sources: K. A. Al-Salahi, (2014). Lumpy Skin disease: Review of literature. MRSVA. 3 (3), 6-23

FIELD INSPECTION:

- Generalised skin nodules and characteristic inverted conical necrosis of skin nodules (sitfast), lymph node enlargement.

- Persistent fever, emaciation, and low mortality.

- Pox lesions in mucous membranes of the mouth, pharynx, digestive tract, nasal cavity, trachea, and lungs.

- Lung features include oedema, focal lobular atelectasis, and pleuritis with mediastinal lymph node enlargement.

- Diagnostic histopathological features include congestion, haemorrhage, oedema, vasculitis, and necrosis involving all skin layers, subcutaneous tissue, and adjacent musculature. Lymphoid proliferation, oedema, congestion, and haemorrhage. Vasculitis, thrombosis, infarction, perivascular fibroplasia, cellular infiltrates.Intracytoplasmic eosinophilic inclusions may be observed in different cells.

LABORATORY INVESTIGATION:

Virus Isolation

– Collect samples during the initial week of clinical signs.

– Utilise skin biopsies, buffy coat, or lymph node aspirates.

– Culture the virus in tissues of bovine, ovine, or caprine origin.

Electron Microscopy

– Display the virus in biopsy specimens.

– Capri-pox virions exhibit an oval profile with dimensions of 320 x 260 nm.

Fluorescent Antibody Tests

Agar Gel Immunodiffusion

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

PCR and LAMP Assay

Serology

– Utilise frozen sera from animals in both acute and convalescent phases.

– Employ virus neutralisation and indirect fluorescent antibody tests.

– Utilise ELISA for the detection of antibodies.

– Exercise caution with agar gel immunodiffusion tests.

– Conduct Western blot analysis, although it is costly and intricate.

Treatment

Lumpy skin disease, stemming from a viral cause, currently lacks a definitive cure. Nevertheless, in inevitable instances, antibiotics, anti-inflammatory medications, or vitamin injections may be used to deal with secondary bacterial infections, manage fever or inflammation, and enhance the animal’s appetite.

ETHNOVETERINARY MEDICINE:

Ethnoveterinary medicine involves utilising the beneficial compounds found in medicinal plants to treat diseases, offering an alternative to allopathic medicine. This approach can mitigate losses in productivity, reduce expenses associated with conventional medicine, and minimise side effects. The National Dairy Development Board (NDDB) recommends specific oral and topical formulations for effective disease treatment.

Oral treatment during the initial three days of infection

| Components | Quantity |

| Break leaves | 10 nos. |

| Black pepper | 10 nos. |

| Crystal salt | 10 grams |

| Jaggery | As per requirement |

- Grind the mentioned ingredients thoroughly and create a paste by incorporating jaggery.

- Administer the paste to affected animals every 3 hours for the initial 3 days.

- Provide three doses every three hours on the first day (Day 1).

- From the second day onward, administer three doses daily for two weeks.

- Fresh dose should be prepared.

Oral therapy from the third to the fourteenth day of the infection

| Components | Quantity |

| Garlic | 2 nos. |

| Coriander leaves | 15 grams |

| Cumin seeds | 15 grams |

| Tulsi | 1 hand full |

| Clove leaves | 15 grams |

| Black pepper | 15 grams |

| Beta leaves | 5 nos. |

| Small onions | 2 nos. |

| Turmeric powder | 10 grams |

| Neem leaves | 1 hand full |

| Jaggery | As per requirements |

- Thoroughly grind the mentioned ingredients, blend them with jaggery.

- Administer the paste to the animal three times daily (morning, evening, and night).

- Prepare a fresh dose daily.

Topical therapy for an open wound.

| Components | Quantity |

| Acalypha Indica leaves | 1 hand full |

| Garlic tooth | 10 nos. |

| Neem leaves | 1 hand full |

| Tulsi | 1 hand full |

| Turmeric powder | 10 grams |

| Heena leaves | 1 hand full |

| Coconut oil | 500 ml |

Grind the listed ingredients and simmer them in 500ml of coconut oil.

- Apply the oil to the cleaned wound once it has cooled adequately.

In case of maggot infestation: Anona leaf paste or coconut oil with camphor is particularly effective on the first day if maggots are present in the wound.

Prevention and Control

- Controlling the disease in endemic areas requires vaccination, along with movement restrictions and the removal of affected animals.

- Recommended control strategies include culling affected animals, imposing movement restrictions, and ensuring compulsory and consistent vaccination.

- Enabling veterinarians and livestock workers to diagnose clinical cases promptly would aid in slowing the spread of the disease through education.

- Capripoxvirus members offer cross-protection, allowing the use of both homologous (Neethling LSDV strain) and heterologous (sheeppox or goatpox virus) live attenuated vaccines to safeguard cattle from LSD infection.

- Swift implementation of eradication measures, including quarantine, slaughtering affected and in-contact animals, proper disposal of carcasses, premises cleaning and disinfection, and insect control, is crucial during disease outbreaks.

References

Al-Salihi, K. (2014). Lumpy skin disease: Review of literature. Mirror of research in veterinary sciences and animals, 3(3), 6-23.

https://atariz1.icar.gov.in/pdf

Mulatu, E., & Feyisa, A. (2018). Review: Lumpy skin disease. J. Vet. Sci. Technol, 9(535), 1-8.

Sources: K. A. Al-Salihi, (2014). Lumpy Skin disease: Review of literature. MRSVA. 3 (3), 6-23

Tulman, E. R., Afonso, C. L., Lu, Z., Zsak, L., Kutish, G. F., & Rock, D. L. (2001). Genome of lumpy skin disease virus. Journal of virology, 75(15), 7122-7130.

https://www.msdvetmanual.com/integumentary-system/pox-diseases/lumpy-skin-disease-in-cattle

https://www.pirbright.ac.uk/lumpyskin

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/lumpy-skin-disease-virus

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9635543/