Metabolic Disorders of Animals

Mohit Bharadwaj 1*, B.C Mondal2, Manoj Kumar Singh3, Sachin Dongare4, and Sumit Gangwar5

1,4,5 Ph.D Scholars, 2Professor and 3Assistant Professor

1,2Department of Animal Nutrition, College of Veterinary and Animal Science,

B. Pant University of Agriculture and Technology, Pantnagar, Uttarakhand -263145

3Department of Livestock Production and Management,College of Veterinary and Animal Science, SVPUAT, University of Agriculture and Technology, Meerut, Uttar Pradesh -250110

4,5 Department of Livestock Production and Management,College of Veterinary and Animal Science, G. B. Pant University of Agriculture and Technology, Pantnagar, Uttarakhand -263145

*Corresponding Author Email id: – bharadwajmohit1@gmail.com

Introduction

The term “metabolism” refers to the collection of all physical, chemical, and metabolic activities that take place within a live cell or organism in relation to the absorption, disintegration, or synthesis of essential organic components. Numerous metabolites that are either utilised as building blocks or destroyed and expelled from the body as waste are released as a result of metabolic activities. During metabolism, nutrients are converted into energy that is used by cells, organs, systems, or the entire organism for healthy bodily function. Therefore, all metabolic activities that enable life and regular organ function are included in metabolism. When one or more metabolic pathways are dysfunctional, other organ systems or the entire body may also be affected. Metabolic disease or disorder is characterised by disruption of one or more metabolic processes that are connected to the control of a specific metabolite in body fluids.

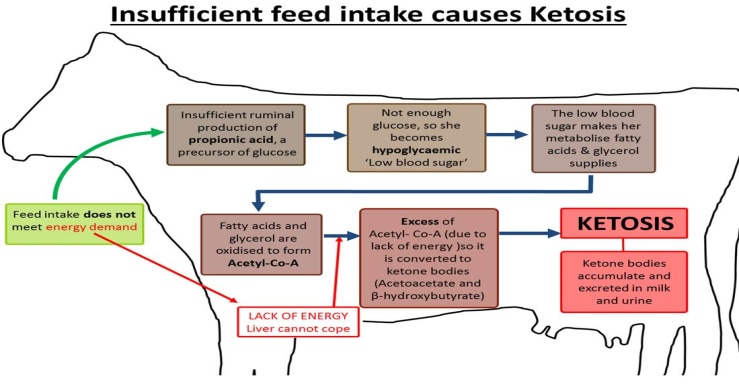

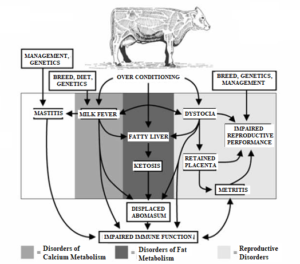

Fig-metabolic disorders often occurs in predictable sequence or cascade

(Source – https://slideplayer.com/slide/16653943/)

A series of ailments known as metabolic disorders of cattle affect dairy cows right after giving birth. The following metabolic abnormalities are the most frequently found in dairy cows within the first month following parturition: (1) subacute and acute ruminal acidosis, (2) laminitis, (3) ketosis, (4) fatty liver, (5) left displaced abomasum (LDA), (6) milk fever, (7) downer cow, (8) retained placenta, (9) liver abscesses, (10) metritis, (11) mastitis, and (12) bloat. These illnesses are referred to as metabolic disorders because they are linked to the disruption of one or more blood metabolites in ill cows. For instance, fatty liver is linked to increased non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA) and their accumulation in the liver, while acidosis is linked to increased production of organic acids (such as acetic, propionic, and butyric acids). Ketosis is also linked to increased levels of ketone bodies (i.e. beta-hydroxybutyric acid – BHBA) in the blood. metabolic disorders in dairy cattle, which are illnesses involving disruption of one or more metabolic processes in the body. For dairy cows, the transition period—which lasts for three weeks before and three weeks after parturition—is extremely important. The transition from a non-lactating to lactating state, hormonal changes, a significant decrease in feed consumption, and a change in diet from a roughage-based diet (such as hay and grass) to one high in fast fermentable carbohydrates are all connected with this time period (i.e. high-grain diets). One or more metabolic diseases affect one out of every two dairy cows in a herd. Although the pathogenesis and aetiology of the majority of metabolic illnesses are not fully understood, numerous preventive and therapeutic approaches have been developed over time.

Low rumen pH, rumen metabolism, and milk fever are all linked to lower blood calcium levels. Some metabolic illnesses, like downer cow, LDA, metritis, mastitis, laminitis, retained placenta, and bloat, still lack a blood metabolite. The most intriguing finding in relation to the prevalence of metabolic disorders is how closely they are related to each other. For instance, milk fever-affected cows are more likely to develop mastitis, retained placenta, metritis, LDA, distocia, udder edoema, and ketosis, while acidosis-affected cows are more likely to develop laminitis, LDA, milk fever, mastitis, and fatty liver. Metritis, LDA, and ketosis are more common in animals with retained placenta. In cows with milk fever, mastitis, laminitis, LDA, metritis, retained placenta, and udder edoema, ketosis and fatty liver are frequent findings.

What is Transition Period

- According to custom, it lasts from dry off through parturition.

- more accurately known as these 4 distinct physiological states that the cow experiences:

- Late lactation

- Dry period

- Parturition

- Early lactation

Why A Transition Period

- Diets for dry cows are frequently hefty and lacking in nutrients.

- When cows freshen (milk production begins), they introduced immediately to very dense (energy rich) ration

- This could cause a lot of issues if not handled appropriately.

Milk fever

Milk fever (Parturient Paresis), also known as hypocalcaemia, is a condition that can be avoided in lactating dairy and beef cows. Milk fever affects five to eight percent of cows.It is a metabolic disease known as milk fever or hypo-calcaemia is brought on by a lack of calcium.

Therefore, milk fever-affected cows will have reduced calcium levels in their blood.

Usually, this disease shows up within the first 24 hours after calving.In some circumstances, it may even happen up to three days after calving.Both the immune system of the cow and muscular function are significantly influenced by calcium.Therefore, if blood calcium levels are too low, they won’t be sufficient to maintain nerve cell function or muscle contractions.

The clinical signs of milk fever can be classified into three stages:

- Stage 1:The cow may appear agitated and tremble and tense her muscles (may go unnoticed). – reluctance to move or eat; the animal may stagger and/or develop stiff hind limbs.

- Stage 2:The cow will typically have a “kink” in her neck or her head curled along her flank and will be discovered lying down or sitting down and unable to get up. Poor body temperature, low body lustre, hard breathing, rapid heartbeat

- Stage 3:Cows frequently appear to be unconscious and unresponsive. The animal will extend its legs out and lie on its side; bloat frequently occurs and regurgitation is likely:- The majority of animals in this stage will perish if untreated.

Common observable symptoms in milk fever

- An uneven walk is the first sign of the condition. It might be apparent during the day. When the cow eventually settles down, you will notice that her ears are cold and typically droopy.

- Early signs include paddling with the back feet and swaying as if about to fall over if the cow is on her feet. Once she is on the ground, she will turn her head and neck to the side as if she had a kink. Her nose starts to dry up.

- Another warning signal is if your cow suddenly loses her energy and attention after being alert and attentive while tending to her new calf. Although this could be a sign of any illness, at this point in your cow’s life, you should suspect milk fever.

- If not treated, the symptoms get worse until the cow passes out, her pulse slows down, and she starts to go cold (you can feel this initially in her legs, ears, and other extremities). She doesn’t recognise you anymore. There is no more rumen activity. She will eventually lose the ability to support her head and collapse, gasping for air, after a period of time.

Nutritional precautions against milk fever

The feeding practises used both during pregnancy and right after calving directly affect the incidence of milk fever. By using the proper feeding techniques throughout the aforementioned times, milk fever can be avoided. The following feeding techniques are advised for dairy cows that produce a lot of milk in order to avoid milk fever.

Calcium restriction during the prepartum (before giving birth) period

Animal life depends on calcium for a number of processes. Calcium is an essential mineral. Calcium shouldn’t ever be added before calving as a milk fever preventative measure. Dietary calcium intake should be low as well (about 20 g per day). When taken a week or so prior to calving, vitamin D considerably reduces the risk of milk fever and aids in the absorption of calcium from the digestive tract. However, because the often offered forages and concentrates include considerable amounts of calcium, it might be challenging to manipulate the ration to ensure low calcium intake. Zeolite and vegetable oils can be added as supplements in this case because both are proven to sufficiently inhibit calcium absorption.

Magnesium supplementation

Another vital mineral is magnesium, which makes up 70% of the body and is primarily found in bones. Magnesium is important to the health of the heart, skeletal muscles, and brain system because it helps keep membranes stable. It is connected to a number of enzymes needed for body metabolism and, most significantly, it is crucial for calcium metabolism. Magnesium is crucial for keeping the level of calcium in an animal’s blood, which makes it indirectly responsible for the development of milk fever. Milk fever in dairy animals can be avoided by supplementing with magnesium at a rate of 15 to 20 g/day coupled with a source of readily digested carbohydrate. Magnesium should be given throughout pregnancy at a rate of 0.4% of dry matter of the diet.

Supplementation of calcium to susceptible animal after calving

Using this approach as your first line of defence against something is not advised. Given that there is a potential that calcium homeostatic pathways would be disrupted, supplementation should be done based on the calibre and calcium content of the food being delivered.

Down Cow Syndrome

When a cow is unable to stand, it becomes recumbent. When a cow is lying down, it is frequently referred to as being “down,” and when it has been down for a while, it is referred to as a “downer cow.”

(Source- https://www.pashudhanpraharee.com/downer-cow-syndrome-treatment-and-management/)

There are many causes of a downer cow, including:

- Injury at or immediately following calving: Bone fracture or paralysis

- Metabolic: hypomagnesaemia or milk fever (hypomag or grass staggers)

- Mastitis or metritis are toxic diseases.

When the primary cause is eliminated but the cow still doesn’t rise, it becomes a downer cow. Due to muscular and nerve injury, this failure to rise is typically noticed within 24 hours of the cow falling off her feet. Damage happens from a cow falling off its feet, which puts a lot of pressure on its muscles and nerves. Many conditions make this worse since the cow is unable to change positions to stop continuous carrying of weight.The primary causes of recumbency can be divided into 4 categories, and remembered with the mnemonic MINT:

Metabolic

- Metabolic

- hypocalcaemia

- hypokalaemia

- nutritional acidosis

- ketosis

- fatty liver disease

- Inflammatory

- Acute septic metritis

- Acute mastitis

- Acute peritonitis (eg. traumatic reticulitis/ruptured uterus)

- Neurological

- Obturator, sciatic or femoral nerve paralysis (eg calving paralysis is damage to L5/L6 outflow of obturator and sciatic)

- Traumatic

- fractured femur

- dislocated hip

- muscle, tendon or ligament rupture

Timings and impact (6 hours down)

- The weight of the cow causes damage to its muscles, nerves, and joints.

- It has been shown that just 2% of dairy cows treated for milk fever within six hours developed a downer cow. Seven to twelve hours without treatment:

- More than 25% developed depressive tendencies. Not treated till 18+ hours.

- Almost 50% of cows that weren’t treated until after 18 hours couldn’t get up.

Clinical Signs

- A cow that just had calves (usually less than 48 hours)

- Unable to stand up for some unknown reason

- Lie with your back straight (on the breast bone)

- Alert, frequently eating, drinking, and peeing and pooping

- Few attempt to stand up, but few move around on their forelimbs (creeper cows)

Diagnosis

- Based on the above-mentioned clinical symptoms

- Because the downer cow is an exclusionary diagnosis, a vet visit is necessary to rule out conditions like metritis, broken bones, nerve paralysis, and peculiar milk fevers.

- Blood tests and the presence of reflexes can both be highly helpful in determining the prognosis.

Treatment

- If you’re housed, move to a well-bedded yard or loose-box

- The secret to success is quality nursing care. Give the cow access to food and water in convenient, wide-

- based containers, shelter, and a soft surface. If the cow isn’t shifting its weight, be sure you force it to do so at least twice a day.

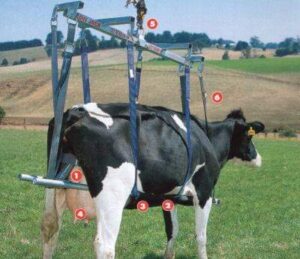

- Raising the cow mechanically, like using a sling, can be helpful for treatment and diagnostics. To increase support if there is nerve injury, hobbling could be useful.

- Keep a watchful eye out for toxic mastitis because it can develop in cows with no history of mastitis.

- Supplement with calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium as needed

- In cases that are more serious, local disinfection and treatment are required.

Prevention

A challenging calving was the main issue in 46% of downer cows. Good calving management is therefore essential. Although there are many elements that affect good calving management, the following four are perhaps the most crucial ones:

- Create a healthy habitat that is clean, dry, and has low stocking densities.

- Verify that the cows’ BCS values at calving are between 2 and 3.5.

- Keep a safe distance and avoid getting too involved.

- Recognize when to ask for and accept support.

- Pick a bull with a high grade for calving ease.Milk fever was the main reason for 38% of the downer cows. The quantity of downer cows will be drastically decreased if milk fever is prevented (see NADIS fact sheet on milk fever)

Grass Tetany

Hyperexcitability, muscular spasms, convulsions, respiratory distress, collapse, and death are all symptoms of hypomagnesemic tetany, a complex metabolic disturbance characterised by hypomagnesemia (plasma tMg 1.5 mg/dL [0.65 mmol/L]) and a reduced concentration of tMg in the CSF (1.0 mg/dL [0.4 mmol/L]). The loss of Mg in milk makes adult lactating animals the most vulnerable. Hypomagnesemic tetany can affect breastfeeding beef cows fed silage indoors, but most typically affects animals grazing on lush grass pastures or green cereal crops. Although it rarely happens in cattle that aren’t breastfeeding, it has happened when undernourished animals were given access to green cereal crops.

(Source – https://www.agridirect.ie/article/silent-killer-grass-tetany-and-how-to-prevent-it)

Cause: The grass tetany season lasts from February to April, and it is characterised by low levels of magnesium or calcium in cattle eating ryegrass, small grains (such as oats, rye, and wheat), and cool-season perennial grasses (such as tall fescue, orchardgrass). This time of year typically sees a burst of new forage growth. Forages cultivated on soils that are low in magnesium, moist, or that are high in potassium and nitrogen but low in phosphorus may have very low levels of magnesium and calcium. Additionally, a lot of spring calves are born and nursing during this time of year. Cattle that are lactating, especially those in the herd that produce the most milk, are most frequently afflicted by grass tetany.The needs of breastfeeding cattle in terms of magnesium and calcium are significantly higher than those of dry cattle. This makes cattle more susceptible to grass tetany while lactating. When the amounts of magnesium and calcium in forages are insufficient to meet the needs of cattle and cattle are not given enough magnesium and calcium supplements, grass tetany develops. Nervousness, muscle twitching, and stumbling while walking are clinical indications of grass tetany. If untreated, an infected animal may collapse on its side, go into convulsions, and endure muscle spasms.

Prevention:Dolomitic lime, which includes magnesium, should be applied to pastures lacking in magnesium. Since plants might not be able to absorb enough magnesium in wet conditions, this might not be useful in avoiding grass tetany on waterlogged soils. Magnesium levels in pasture may benefit from phosphorus fertilization as well. However, it is important to take into account the environmental issues related to high soil phosphorus levels. When included in the fodder regimen, legumes (such as clovers, alfalfa, and lespedezas) are frequently high in magnesium and may help lower the risk of grass tetany.The best way to prevent grass tetany is to boost your diet with extra calcium and magnesium throughout the grass tetany season. Both can be a part of a mineral supplementation regimen by being incorporated into a mineral mix. One month before grass tetany season, start feeding a high magnesium mineral.

Hypomagnesemic Tetany in Calves

When calves are fed milk, the efficiency of magnesium absorption decreases, going from 87 percent at 2-3 weeks to 32 percent at 7-8 weeks. In 2- to 4-month-old calves being fed just milk or in younger calves with persistent scours being fed milk substitute, hypomagnesemic tetany can develop. Clinical symptoms include hyperexcitability, muscle spasms, convulsions, and death and are comparable to those of hypomagnesemic tetany in adult cattle (see above).Acute lead poisoning, tetanus, strychnine poisoning, polioencephalomalacia, and enterotoxemia brought on by the Clostridium perfringens toxin must be distinguished from hypomagnesemic tetany in calves. Bone analysis helps with diagnosis; in calves with hypomagnesemia, the Ca:Mg ratio may be as high as 90:1 from normal bone’s 70:1 ratio. A 10 percent solution of magnesium sulphate (100 mL, SC) must be administered right away to affected calves, followed by 10 g of magnesium oxide each day, orally. The condition can be avoided by giving animals high-quality legume hay and a beginning diet starting at two weeks of age.

(Source- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grass_tetany)

Ketosis in Dairy Cows

The first six weeks of lactation are the most frequent time that dairy cows experience the metabolic illness ketosis. There are no regional names for ketosis in East Africa; it is also known as acetonemia or ketonemia in English. Adult cattle commonly suffer from ketosis. Early lactation is when it generally affects dairy cows and is most frequently characterised by partial anorexia and sadness. Rarely, it affects cattle in the late stages of pregnancy, when it resembles pregnancy toxaemia in ewes.Along with lack of appetite, occasionally people will notice indicators of nerve dysfunction such pica, abnormal licking, unsteadiness and strange walking, bellowing, and hostility. Despite having a global distribution, the illness is particularly prevalent in areas where dairy cows are bred and raised for high production.

Cause

The primary culprit is a confluence of high energy requirements at the start of lactation and insufficient energy in the feed (e.g. poor quality silage, very coarse hay). A cow is only able to consume a certain amount of fodder each day. The animal has a net energy loss that worsens over time and lowers blood sugar levels if the energy provided by the ingested feed is less than what the cow needs. The liver transforms body tissue (protein, fat) into more glucose to supply more energy (sugar). Ketone bodies, which are harmful byproducts of this process and must be eliminated, are produced. The cow becomes ill if the blood’s ketone concentration is too high.

Signs and Symptoms

The highest productive dairy cows are impacted by ketosis, which starts with extremely subtle symptoms that are first simple to ignore. Animals that are affected eat less and produce less milk. The cow seems to be dozing off and often excretes solid waste that is mucous-covered. The animal loses weight quickly (using its energy reserves) if the condition gets worse. Cattle that are ill may try to eat odd feed in addition to refusing to eat grain, concentrate, or dairy flour (coarse straw, twigs, soil, abnormal objects). Due to the increased ketone levels, the animal stands with a humpback and some exhibit a peculiar fruity to musty odour in their breath and urine. Untreated cows may exhibit strange behaviour (such as staggering, circling, head pressing, continuous licking, bellowing – like Rabies! ), lose their ability to stand, and have other health issues.

Type II ketosis is occasionally used to define ketosis during the first few weeks after giving birth. Such instances of very early lactational ketosis are typically accompanied by fatty liver. Ketosis and fatty liver are likely two of a range of ailments connected to excessive fat mobilisation in cattle. Ketosis cases that appear closer to the time when milk production peaks, which is typically between 4-6 weeks after delivery, may have less to do with excessive fat mobilisation and more to do with underfed cattle who are experiencing a metabolic deficit of gluconeogenic precursors. This stage of ketosis is sometimes referred to as type I ketosis.

Clinical Findings:

Reduced feed intake is typically the first indication of ketosis in cows kept in stalls. When given meals in parts, cows in ketosis frequently prefer grass to grain. The earliest indicators of ketosis in group-fed herds are typically reduced milk output, lethargy, and an abdomen that seems “empty.” Physical examination reveals that cows are febrile and possibly mildly dehydrated. Rumen motility varies, sometimes being hyperactive and other times hypoactive. There are frequently no additional physical problems. In a small percentage of instances, CNS abnormalities are detected. These include unusual licking and chewing, with cows occasionally gnawing unceasingly on pipes and other nearby things.

(Source – https://www.farmhealthonline.com/disease-management/cattle-diseases/ketosis/)

Prevention and Control:

Nutritional management is a way to avoid ketosis. Late in the lactation period, when cows typically grow overweight, body condition should be controlled. It may be possible to help allocate dietary energy toward milk production and away from body fattening by modifying the diets of late lactation cows to boost the energy supply from digestible fibre and decrease the energy supply from starch.

Typically, it is too late to lower the bodily condition score after the dry season. Reducing body condition throughout the dry period, especially in the late dry period, may even be harmful since it causes an excessive mobilisation of adipose tissue prior to delivery. Maintaining and encouraging feed intake is a crucial component of ketosis avoidance. In the latter three weeks of gestation, cows typically consume less feed.Aiming to reduce this decline should be the goal of nutritional management. Regarding the ideal dietary qualities during this time, there is debate. It’s possible that the ideal amounts of energy and fibre for cows in the final three weeks of pregnancy differ from farm to farm.

Throughout the whole dry period, feed intake should be monitored and diets should be modified to meet but not significantly exceed energy requirements. The average daily energy requirement during the dry period for Holstein cows with typical adult body sizes is between 12 and 15 Mcal expressed as net energy for lactation (NEL).Diets should encourage quick, persistent increases in feed and energy intake after calving. Early lactation rations should have enough fibre to sustain rumen health and feed intake while still being somewhat high in non-fiber carbohydrate concentration.

Neutral-detergent fibre concentrations should typically be in the 28–30% range, while nonfiber carbohydrate concentrations should be between 38–41%. The ideal ratios of the different carbohydrate components will depend on dietary particle size. Niacin, calcium propionate, sodium propionate, propylene glycol, and rumen protected choline are a few feed additions that may aid in managing and preventing ketosis. These supplements must be given during the last 2-3 weeks of pregnancy as well as during the vulnerable phase to ketosis for them to be effective. Monensin sodium has received approval in several nations for use in avoiding disorders linked to subclinical ketosis and related symptoms. Where authorised, it is advised to administer 200–300 mg per head each day.

Some farms test every cow during the early lactation period using hand-held BHB metres. Propylene glycol is used to treat cows with subclinical ketosis. Although labor-intensive, this method has been shown to decrease the spread of disease in subclinicallyketotic animals and increase milk output in those that have received treatment.

Pregnancy Toxaemia in Cow/Sheep

Pregnancy toxaemia, often known as fat cow syndrome, mostly affects cows who were previously well-fed and in good physical condition in late pregnancy when their food intake is reduced. In the latter two months of pregnancy, over-fat pregnant cows given insufficient nutrition may develop a condition similar to pregnancy toxaemia (twin lamb illness) in sheep. In fatty beef cattle, a lack of feed results in the transfer of significant amounts of body fat to the liver. Pregnancy toxaemia is especially contagious in fat pregnant cows, particularly those with weak teeth or those giving birth to twin calves. The condition affects cows who are in their final two months of pregnancy or who have just given birth, and it is more prevalent in first-calf heifers than in older cows. Pregnancy toxaemia is caused when pregnant beef cows’ diets are changed from a good quality diet to a poor quality diet in an effort to reduce body weight and improve ease of calving.

(Source-https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Therapeutic-management-of-pregnancy-toxemia-in-a-Chandana-Padmaja/9970f1721e934fc7cf50306dda0dfaac7c448498)

Cause of the disease

In the form of glucose, pregnant cows need a lot of ready energy to support their growing calves. There are two sources for this. The meal that is ingested through the rumen is first converted to glucose in the liver. Second, fat stores are released and transported in the circulation to the liver where they are converted to glucose by the liver. To make up for the shortfall that usually happens during pregnancy, when energy demands are high, this is a typical process.The issue arises because the liver requires a specific amount of glucose in order to use the incoming fat. When the animal consumes relatively little high-quality feed or when the fat is ingested at a rate that exceeds the liver’s capacity to produce glucose, the liver begins to accumulate fat. Ketones build up to high blood levels, the liver enlarges, turns pale and fatty, and they start to have an impact on the brain. The animal quits eating as a result of impaired brain function.

Signs and Symptoms to look out for in Cattle

- Pregnant

- A lesser or nonexistent hunger

- melancholy and depression

- Separate from the herd. 5. Nasal breathing. 6. A sweet, acetone-like odour can be detected on their breath. 7. Neurological symptoms (staggering, aggression, delirium)

- Downer cows become recumbent 2–2 weeks before they pass away.

- Death

Prevention

Nutritional control is key to prevention. At calving, cows should be in good condition (condition score of 3 or higher), and the post-calving feed supply should be of adequate quality and quantity to prevent significant condition loss in the lactating cows. Planning ahead is essential for avoidance of this disease, which in some regions manifests in patterns. For instance, autumn calving in southern New South Wales before the winter rain will result in cows being significantly pregnant when the quality of the feed is low.

The first weather break will upset pregnant cows and severely degrade the quality of the dry grass. Supplemental feeding with high energy feeds (like grain) in these circumstances will stop pregnant toxaemia. Simply taking protein meal supplements won’t be enough to keep the disease at bay. They do not receive enough food to meet their needs for energy. Feeding late-pregnant cows with high-quality feed is a smart idea. Alternately, select late-gestational cows and provide early supplemental feeding. When there are dry seasons, these cows are the first to suffer, especially if they are part of a mixed mob.

Supplementary feeding practices

The quality and quantity of the feed at hand will determine how much additional feeding is necessary. Breeding cows experience periods where intake is insufficient to meet needs, even on high-quality feed. Cows can typically handle this by utilising their fat reserves, but as the quality of the diet deteriorates, the risk of pregnant toxaemia rising. Therefore, supplemental feeding becomes more crucial as pasture quality and quantity deteriorate. Low-quality pastures have a decreased nutrient content and digestibility, reducing their intake.

The following supplements for dry-paddock (more than 1500 kg DM/ha) feeding of late-pregnant and/or lactating cows each provides equivalent energy:

- silage: 10 to 11 kg fresh per head per day

- good hay: 3.5 to 4.5 kg per head per day

- grain: 3.0 kg per head per day

- cottonseed meal: 2.5 kg per head per day

- grain and white cottonseed: 1.25 kg of each per head per day. About 1% calcium should be fed with grain and cottonseed supplements.

Goiter in Animals

It is All domesticated mammals and birds experience thyroid gland enlargements that are not cancerous or inflammatory. Goiter must be distinguished from other causes of swelling in the upper neck, such as enlarged salivary glands or lymph nodes. Although many animals with goitre seem to stay euthyroid, in some cases, particularly in newborns, clinical indications of hypothyroidism may occur.

(Source- http://www.flockandherd.net.au/sheep/reader/goitre.html)

Common causes of goiter include:

- enlarged thyroid gland

- idiopathic

- in-utero iodine deficiency or excess

- iodine deficiency

- iodine toxicity

- ingestion of goitrogenic plants

- hereditary familial goiter

- congenital hypothyroidism and dysmaturity syndrome in foals

Iodine Deficiency in Animals

Iodine deficiency may result from inadequate dietary iodine intake or from consuming feeds that contain substances that either prevent the thyroid gland from absorbing iodine or prevent the normal synthesis of thyroid hormones (goitrogens). The thyroid glands normally expand as a result of iodine shortage (goiter). Thyroid hormone, which is crucial for regulating metabolism, is produced by the thyroid glands, which are situated in the upper ventral neck on the trachea.Animals from places with high rainfall who are raised in iodine-deficient soils may develop goitre, with the risk being highest after heavy rains in the autumn or winter. Animals that had recently grazed specific white clover pastures or brassica crops that were strong in goitrogens may also exhibit goitre.

Clinical Signs and diagnosis

Goiter is most likely the cause of a large, hard, non-fluctuant enlargement of the ventral neck in an otherwise healthy animal. Abscesses in the cheesy gland and bottle jaw are other diagnosis. Thyroid glands must be sent for histopathology in buffered formalin for laboratory confirmation.

References

Albert sundrum (2015). Metabolic Disorders in the Transition Period Indicate that the Dairy Cows’ Ability to Adapt is Overstressed, Animals 2015, 5(4), 978-1020

BeedeD. K.1995 Macromineral Element Nutrition for the Transition Cow: Practical Implications and Strategies. Proceedings of The Tri-State Dairy Nutrition Conference, Wayne,USA, May 11-13, 1995

Casburn, G. (2016). Pregnancy toxaemia in breeding ewes. Wagga Wagga: Department of Primiary Industries NSW Government.

Cebra, C. (2019, May 22). Pregnancy Toxemia in Cows. Retrieved from MSD Veterinary Manual: https://www.msdvetmanual.com/metabolic-disorders/hepatic-lipidosis/pregnancy-toxemia-in-cows

Crnkic, C., & Hodzic, A. (2012). Nutrition and Health of Dairy Animals. Milk Production – An Up-to-Date Overview of Animal Nutrition, Management and Health, 30-63 ,doi:10.5772/50804

Curtis, C.; Erb, H.; Sniffen, C.; Smith, R.; Kronfeld, D., 1985: Path analysis of dry period nutrition, postpartum metabolic and reproductive disorders, and mastitis in Holstein cows. Journal of Dairy Science, 68, 2347-2360.

Goff, J.P.; Horst, R.L. Physiological changes at parturition and their relationship to metabolic disorders. J. Dairy Sci. 1997, 80, 1260–1268

GoffJ. P.2006a Major Advances in Our Understanding of Nutritional Influences on Bovine Health.Journal of Dairy Science.8,94

IngvartsenK. L.2006 Feeding- and Management-Related Diseases in the Transition Cow: Physiological Adaptations Around Calving and Strategies to Reduce Feeding-Related Diseases. Animal Feed Science and Technology, 1263-1267

Janice E. Kritchevsk (2019 Aug,) Goiter in Animals Retrieved from MSD Veterinary Manual: https://www.msdvetmanual.com/endocrine-system/the-thyroid-gland/goiter-in-animals

Sundrum, A. (2015). Metabolic Disorders in the Transition Period Indicate that the Dairy Cows’ Ability to Adapt is Overstressed. Animals, 5(4), 978–1020. doi:10.3390/ani5040395 https://www.msdvetmanual.com/metabolic-disorders/metabolic-disorders-introduction/production-related-metabolic-disorders-in-animals

Metabolic Disorders in Livestock

Metabolic Disorders in Livestock