MILK FEVER IN ANIMALS

Anita Sewaga, Rashmi Singhb, Saksham Mandawatc

a-Ph.D. Scholar, b- Assistant Professor, c- P.G. Scholar

Department of Veterinary Medicine, Post Graduate Institute of Veterinary Education and Research (PGIVER), RAJUVAS, Jaipur

Milk fever is an important production disease occurring most commonly in adult cows within 48-72 hours after parturition, which is characterized clinically by hypocalcemia, general muscular weakness, circulatory collapse and depression of consciousness.

Etiology–

- A depression in the levels of ionized calcium in the extracellular space, including plasma, is the basic biochemical disturbance in milk fever.

- The onset of lactation places such a large demand on the calcium homeostatic mechanisms of the body that most cows develop some degree of hypocalcemia at calving.

- A cow producing 10 kg of colostrum (2.3g of Ca/kg) will loss 23g of Ca in a single milking. This is about 9 times as much Ca as that present in the entire plasma Ca pool of the cow.

Occurrence–

Age – Hypocalcemia at calving is age related and most marked in cows at their third to seventh parturition. Aging also results in a decline in the ability to mobilize Ca from bone stores and a decline in the active transport of Ca in the intestine, as well as impaired production of 1,25(OH)2D3.

Breed- Jersey, Swedish Red and White, and Norwegian Red breeds develop clinical milk fever more frequently than Holstein–Friesian cows. Jersey breed have higher Ca concentration in milk compared to Holstein cows. Differences in the number of intestinal vitamin D receptors regulating the intestinal Ca uptake have been reported in some studies.

Calcium Homeostasis- The following three factors affect Ca homeostasis, and variations in one or more of them may contribute to the development of clinical disease in any individual:

- Excessive loss of calcium in colostrum beyond the capacity of absorption from the intestines and mobilization from the bones to replace it.

- Impairment of absorption of Ca from the intestine at parturition.

- Mobilization of Ca from storage in the skeleton may not be sufficiently rapid or efficient to maintain normal plasma Ca level.

Clinical signs-

The main clinical manifestations are divided into three stages

First stage or Stage of excitement: –

- Anorexia (decreased appetite)

- Nervousness or hypersensitivity

- Mixed excitement or tetany without recumbency

- Weakness or weight shifting

- Stiffness of hind legs

- Rapid heart rate

- Rectal temperature is usually normal or above normal (>39 C).

Second stage or Stage of sternal recumbency: –

- Sternal recumbency comprising down on chest and drowsiness – Characteristic “S” shaped posture

- Sitting with lateral kink in neck or head turned to lateral flank.

- Depression

- Fine muscle tremors

- Rapid heart rate with decreased intensity of heart sounds

- Cold extremities

- Decreased rectal temperature (35.6 to 37.8 C)

- Decreased gastrointestinal activity

- Pupils dilated and unresponsive to light

Third stage or Stage of lateral recumbency: –

- Lateral recumbency, comprising of almost comatose condition, progressing to loss of consciousness

- Severe bloat

- Flaccid muscles

- Profound gastrointestinal atony

- Rapid heart rate

- Impalpable pulse and almost inaudible heart sounds.

Pathogenesis- Calcium has several functions relevant for the pathophysiology of periparturient hypocalcemia, which include the following:

- Cell membrane stability: Calcium bound to cell membranes contributes to the maintenance of adequate membrane stability. In excitable cells the decreased availability of ionized Ca results in higher cell membrane permeability, thereby altering the resting membrane potential and making nerve cells more excitable.

- Muscle contractility: Calcium is required to clear the binding site for myosin on the actin molecule inside the muscle fibers. The cross-bridging between actin and myosin is the basis for the contraction of muscle fibers. Decreased availability of Ca can therefore affect muscle contractility.

- Release of acetylcholine: Calcium is required for the neuronal release of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine into the synaptic cleft of the neuromuscular junctions. Calcium depletion can thus hamper the signal transmission at the level of the neuromuscular endplate

- Cows developing milk fever have higher plasma cortisol concentrations than do non-milk fever cows.

- Muscle tone decreases in most body systems, particularly in the cardiovascular, reproductive, and digestive systems, and possibly in the mammary system. Blood flow to the extremities is reduced, causing the characteristic cold ears of a cow suffering from milk fever.

Diagnosis–

- History taking-

- Occurs in mature cows usually 5-9 years old, within 72 hours after parturition.

- Occurs in highest milk producing period.

- Higher incidence in the Jersey breed.

- Clinical examination- Clinical signs include early excitement and tetany, hypothermia, flaccidity pupil dilation, impalpable pulse, no rumen movement, soft heart sounds, fast heartbeats are fast (80-100 per minutes), decreased reflex, depression coma, bloated and death.

- Laboratory diagnosis

Hypocalcemia- Milk fever can be defined as low blood total calcium (8.0 mg/dl) or low blood ionized calcium (4.0 mg/dl), with or without clinical signs of hypocalcemia. Normal level in a dairy cow is 8-10 mg/dl. Direct determination of blood calcium is the more accurate method to diagnose a case of milk fever.

Differential diagnosis–

Differential diagnosis include toxic mastitis, toxic metritis, other systemic toxic conditions, traumatic injury (eg, stifle injury, coxofemoral luxation, fractured pelvis, spinal compression), calving paralysis syndrome (damage to the L6 lumbar roots of sciatic and obturator nerves), or compartment syndrome. Some of these diseases, in addition to aspiration pneumonia, may also occur concurrently with parturient paresis or as complications.

Treatment–

- The treatment of choice for milk fever is slow, intravenous infusion of 8-12 g of calcium as soon as possible after the onset of clinical signs. Heart rate should be closely monitored for toxic effects. Calcium borogluconate containing products with or without added magnesium and phosphorus are mostly used in the India: usually 400 ml of 40% calcium borogluconate. Recommended treatment is IV injection of a calcium gluconate salt, although SC and IP routes are also used. A general rule for dosing is 1 g calcium/45 kg (100 lb) body wt. Most solutions are available in single-dose, 500-mL bottles that contain 8–11 g of calcium.

- Solution containing dextrose should not be given subcutaneously because of abscess formation.

- During cold weather the solution should be warmed to body temperature. Warming the calcium solution seems to reduce toxic effects also.

- Approximately 85% of cases will respond to one treatment, in many cases cows recumbent from milk fever will raise within 10 minutes of treatment and others will get up 2-4 hours later.

Prevention- Prevention of parturient paresis has been approached by feeding low-calcium diets during the dry period. The negative calcium balance results in a minor decline in blood calcium concentrations. This stimulates PTH secretion, which in turn stimulates bone resorption and renal production of 1, 25 dihydroxyvitamin D. Increased 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D increases bone calcium release and increases the efficiency of intestinal calcium absorption.

Strategies for prevention of periparturient hypocalcemia in general are based on one of following approaches:

- Reduction of dietary Ca available for intestinal absorption during the dry period

- Induction of mild to moderate acidosis during the last weeks of gestation

- Supplementation of vitamin D during the dry period

- Oral Ca supplementation around parturition

- Parenteral Ca administration around parturition

- Partial milking

- Large doses of vitamin D (20–30 million U/day), given in the feed for 5–7 days before parturition, reduces the incidence. However, if administration is stopped >4 days before calving, the cow is more susceptible.

- Doses of 150 g of calcium gel are given 1 day before, the day of, and 1 day after calving.

Dietary Cation-Anion Difference (DCAD) – Most recently, the prevention of parturient paresis has been revolutionized by use of the DCAD, a method that decreases the blood pH of cows during the late prepartum and early postpartum period. The DCAD approach is based on the finding that most dairy cows are in a state of metabolic alkalosis due to the high potassium content of their diets. This state of metabolic alkalosis with increased blood pH predisposes cows to hypocalcemia by altering the conformation of the PTH receptor, resulting in tissues less sensitive to PTH. Lack of PTH responsiveness prevents effective use of bone calcium, prevents activation of osteoclastic bone resorption, reduces renal reabsorption of calcium from the glomerulus, and inhibits renal conversion to its active form. DCAD is expressed in milliequivalents per kilogram of dry matter (mEq/kg DM) or in some instances in mEq/100 g DM. The most commonly used is DCAD4 = (Na++ K+) − (Cl− + S–2), which only considers the four (thus DCAD4) quantitatively most important dietary ions.

Cations have a positive charge like sodium (Na), potassium (K), calcium (Ca), and magnesium (Mg). Cations in the diet promote a more alkaline (higher blood pH) metabolic state which has been associated with an increased incidence of milk fever. Anions have a negative charge such as chloride (Cl), sulfur (S) and phosphorus (P). Anions promote a more acidic metabolic state (lower blood pH) that is associated with a reduced incidence of milk fever.

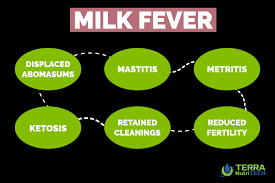

Economic importance– Hypocalcemia is considered to be a “gateway disease” that predisposes to a number of common disorders, such as dystocia, uterine prolapse, retained fetal membranes, mastitis, ketosis, abomasal displacement, ketosis, and immune suppression.