Mithun (Bos frontalis)-A unique bovine species of North Eastern hilly region of India

J.K. Chamuah*, Plabita Goswami, Trishita Banik, Bidyapati Thangjam, Limasungla Imchen, and Narendra V.N

ICAR-NRC on Mithun, Medziphema, Nagaland-797106

*Corresponding author email address: drjayantavet@gmail.com

Abstract

The Mithun (Bos frontalis), often referred to as the ‘cattle of the mountains,’ holds a place of honor in the northeast region of India, prominently in the states of Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Manipur, and Mizoram. This animal symbolizes status, prosperity, peace, and harmony among the tribal communities of these areas. Beyond India’s borders, Mithun can also be found in Myanmar, Bhutan, Bangladesh, China, and Malaysia. Traditionally raised as a ceremonial creature, it is commonly sacrificed for meat during various festivals and social gatherings among tribal groups. Mithun have a preference for dense foliage and are capable of being used for draught work in the challenging terrain of remote hilly landscapes. The favorable climate and environment of these regions, however, makes them prone to a host of diseases, including bacterial, viral, and parasitic conditions. To mitigate disease outbreaks, a stringent health schedule comprising vaccinations and deworming routines is recommended.

Keywords: Mithun, feeding habitat, rearing system, diseases and management.

Introduction

The Mithun, scientifically known as Bos frontalis, is an uncommon type of bovine found in the mountainous forests of northeast India. The origins and domestication process of the mithun are topics of debate among scientists, as its genesis is thought to stem from a now-extinct ancient bovine. It first came to the attention of Europeans in the 19th century during their expeditions into the mithun’s natural habitats. Local legends indicate that the mithun was one of the first animals to be domesticated, originating from a closely related wild species, partly drawn to domestication by its affinity for salt. Three main theories exist regarding the mithun’s origin: 1) it is a domesticated version of the wild gaur; 2) it is a hybrid between a bull gaur and a zebu cow; and 3) it descended from an extinct wild Indian bovine. Genetic studies and available evidence lean heavily towards the mithun being a domesticated form of the wild gaur (Bos gaurus). The concept of the mithun being a zebu and bull gaur hybrid is largely disputed due to a sterility barrier that renders male hybrids sterile, along with a significant difference in appearance between zebus and mithuns, casting doubt on the hybrid and extinct descendant hypotheses. Differences between mithun, zebu, and European cattle have been noted in hemoglobin genotypes, but molecular genetic analysis shows a close kinship between mithun and gaur. The mithun and gaur share many physical traits, with the main distinctions being the gaur’s larger size and massiveness compared to the mithun, which is smaller, more docile, and possesses broader, less curved horns and an extended dewlap. There exists no sterility barrier between mithun and gaur, and they share a karyotype pattern with 29 chromosome pairs. This evidence supports the likelihood that mithun are domesticated gaur, with physical variations resulting from natural selection and human domestication efforts over time. Historically referred to as “mithan” in numerous writings, the mithun and gaur are currently recognized as the same species, Bos frontalis, with “mithun” denoting the domesticated variety. Based on current knowledge, the taxonomic classification of the mithun is as follows: Kingdom: Animalia; Phylum: Chordata; Subphylum: Vertebrata; Class: Mammalia; Subclass: Prototheria; Infraclass: Eutheria; Order: Artiodactyla; Suborder: Ruminantia; Family: Bovidae; Subfamily: Bovinae; Genus: Bos; Species: frontalis.

Distribution and population of mithun

The gaur, a wild relative of the mithun, can be found in the tropical forests stretching across India and the Indochina-Malay Peninsula, which encompasses countries such as India, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, Myanmar, and Malaysia. On the other hand, the mithun’s range is more restricted, primarily to the Indo-China peninsula, though it is also present in small populations within Myanmar, China, Bangladesh, and Bhutan. In India, the mithun is predominantly located in the four northeastern hilly states of Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Mizoram, and Manipur. Additionally, various zoos across the nation house mithuns, showcasing them to the public.

The animal plays a central role in the socio-economic & cultural life of tribal people. It is the State animal of Nagaland and Arunachal Pradesh. As per the 20th Livestock census, the total Mithun population in the country is 3.9 Lakhs, with a 30.6% increase in the population from the last census. Arunachal Pradesh is having the highest number of mithun at 89.7%, 5.98% in Nagaland, 2.36% Manipur, and 1.02% Mizoram.

| STATE | 2003 | 2007 | 2012 | 2019 |

| Arunachal Pradesh | 1,84,343 | 2,18,931 | 2,49,000 | 3,50,154 |

| Nagaland | 40,452 | 33,385 | 34,871 | 23,123 |

| Manipur | 19,737 | 10,024 | 10,131 | 9,059 |

| Mizoram | 1,783 | 1,939 | 3,287 | 3,957 |

| TOTAL | 2,46,315 | 2,64,279 | 2,97,289 | 3,86,293 |

Habitat

Mithun animals thrive best in evergreen forests characterized by moderate environmental temperatures, high levels of precipitation, and medium humidity. These conditions favor the growth of broadleaf trees, which are a primary source of fodder for Mithun. Traditionally, Mithun are raised in subtropical to mild temperate regions adorned with moist or rainforests, utilizing a free-range system in the mountainous areas at altitudes ranging from 300 to 3000 meters above sea level (MSL). These forests boast a diverse flora, including tall trees as the first layer, followed by tall shrubs, evergreen herbs, and vines in the second layer, with a ground cover of various grasses and creepers that have broad leaves and wrap around the larger trees. At higher elevations, Mithun territories overlap with those of yaks, whereas at lower elevations, Mithun and domestic cattle share habitat spaces. The traditional agricultural method known as Jhum, or shifting cultivation, practiced in the area, has detrimentally impacted the forest cover, reducing the forests’ ability to support wildlife. Furthermore, the mountainous terrain coupled with heavy rainfall contributes to soil erosion and the leaching of minerals with runoff water, posing a serious threat to the nutrient balance within the soil-plant-animal ecosystem. In deciduous trees, the nutrient content of the leaves varies significantly with their maturity and the season, affecting the quality of available fodder. These environmental and anthropogenic factors have led to a notable decline in the Mithun population, especially in states like Manipur and Nagaland, due to the degradation of their habitats.

Mithun management in free range

Mithuns are typically allowed to roam free in forests, feeding on the natural vegetation available throughout the year. They are usually brought back to the village only during specific social events such as ceremonies, marriages, and festivals, mainly for the purpose of being slaughtered. To prevent overgrazing and help conserve the forest environment, these animals are traditionally shifted from one area to another every few months. This practice of rotational grazing is becoming more challenging due to the growing need for agricultural land. The reduction and degradation of forest areas are negatively impacting mithun rearing, prompting farmers to contain them within specified areas using fencing to protect their crops.

In locations like Khomi village in Nagaland’s Phek district, it has been noted that farmers make it a point to bring their mithuns back to the community for a few days each month. They provide them with food such as tree leaves, maize stubble, and other crops, and use permanent structures for their housing. This method helps in making the mithuns more accustomed to their human counterparts and generally results in animals that are easier to manage compared to those raised entirely in the wild. Special attention is given to females close to giving birth or those with newborn calves, often bringing them into the farmer’s home for a few days for extra care. The care of mithuns in the forest is entrusted to a group of 3 to 5 adept young individuals known as “Mithun Men,” chosen by the local Mithun Farmers Association. While the mithuns themselves do not have shelters in the forest, temporary accommodations are built for their caregivers. The mithuns are raised with minimal intervention, with common salt being one of the few supplements provided to them. This not only helps in maintaining the animals’ health but also strengthens their bond with the caregivers and their owners. For water, the animals rely solely on natural sources such as perennial streams or springs within the forest.

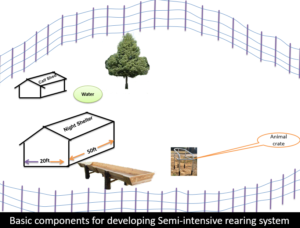

Mithun management in semi intensive system

Mithun can be kept in a semi-intensive management system on farms, similar to other animals. This approach lessens the animals’ stress from harsh weather conditions and boosts their growth and productivity. In forest areas, temporary shelters equipped with tying posts for the animals can be built using resources found locally. It’s possible to train Mithun to return to these shelters in the evenings. This practice allows caretakers to regularly check on the animals. The National Research Centre (NRC) on Mithun implements this semi-intensive system at their campuses in Medziphema and Porba, Nagaland, as well as at state-run farms in Sagali, Arunachal Pradesh, and in Mizoram.

Space requirement

Since, the adult body weight and growth rate of mithun are comparable with cattle (Bos indicus), standard space requirements for different categories of cattle may be followed for mithun as well. The standing floor space requirements for different categories of mithun are given in Table – 2 as per the recommendation for cattle.

Table 2. Floor space requirements for mithun (Thomas and Sastry, 1991)

| Type of mithun | Floor space requirement (m2) | Maximum number of animals to be kept | Height of the shed (cm) |

| Adult bulls | 12.0 | 1 | 200 |

| Adult cows | 3.5 | 50 | 200 |

| Young calves | 1.0 | 30 | 175 |

| Growing males and female | 2.0 | 30 | 200 |

| Animals at late pregnancy/ calving (calving shed) | 12 | 1 | 200 |

Table 3. Space requirements for feed and water trough (Thomas and Sastry, 1991)

| Type of mithun | Space/Animal (cm) | Dimension of the manger (cm) | ||

| Width | Depth | Height of the outer wall | ||

| Adult | 60-75 | 60 | 40 | 50 |

| Calves | 40-50 | 40 | 15 | 20 |

Advantages:

- Less space requirement

- Scope for diversified use of mithun for meat, milk, hides and draught purposes

- Better nutrient supplementation and increase in productivity

- Animal identification is easier

- Regular monitoring of animal growth, health, breeding and reproduction

- Reduce incidence of predator attack on calf

Feeding behavior and management

Mithuns are browser like goat and they prefer to browse on delicate tree leaves and twigs of trees, shrubs and bushes in jungle which generally other bovine doesn’t prefer. Broad-leaf trees like Ficus hookerii are highly relished by them. They cover a long distance during their course of browsing. Heat tolerance capacity of mithun is very less, hence during the noon hours they retire to the deepest part of the forest in search of water especially oozing from the natural salt lick sources, ponds or streams to quench their thirst and takes rest to ruminate near by the spots. Such spots of natural salt licks sources become the regular place of visit for the mithun. In the evening they move out in open area and continue browsing till late evening.

As grazer they are very much selective and prefer certain species of herbage, stages of growth and particular parts of the forage and are generally found to be concentrated in a particular area of the forest abundant in particular species of plant.

- Mithun exhibits browsing habit and they browse on varieties of natural tree leaves, shrubs and bushes present in the natural vegetation.

- It is traditionally reared under free range forest ecosystem. Animals are let loose in the forest and they survive at the sole mercy of nature by grazing on natural fodder shrubs, herbs and other natural vegetation.

- It is raised as a community herd in designated forest areas specifically by the mithun society.

- Occasional salt lick is provided from time to time.

- During the seasons of cultivation, mithuns are usually confined into community enclosures which are erected with locally available wooden posts or bamboo where the quick growing shrubs, grasses, tree leaves and water sources within the enclosures meet the daily requirements of the animals

Mithun as a source of Meat and Milk:

Mithun meat:

- Composition of mithun meat muscle (%): Protein:14-19; Crude fat: 0.4 -3.5; Carb: 0.4 -4.9

- Higher dressingpercentage than cattle: 58.82± 62 vs 55.96 ± 0.60 (On similar level of feeding)

- Mithun meat is leaner (12.93±1.89 vs 28.47± 1.09 kg fat) and more tender than beef

- Developed value added meat products (patties and nuggets)

Processing technology for traditional meat products like mithun meat pickle, mithun momo, smoked mithun meat with suitable packaging technology for preserving its quality and shelf have been developed. A variety of mithun meat products such as nuggets, patties, sausages, slices, meatballs could be produced and have a potential scope for meat industry in near future.

(Source-ICAR-NRCM Publication)

(Source-ICAR-NRCM Publication)

Comparative carcass quality

| Items | Mithun | Tho tho cattle |

| Live weight (kg) | 367.7±10.91 | 352.7±10.68 |

| Skin weight (kg) | 28.07±0.7 | 20.37±1.66 |

|

Meat quality |

||

| Slaughter weight | 349.3±11.59 | 344.8±10.08 |

| Dressing % percentage, meat | 58.82±0.62 | 55.96±0.6 |

| Body fat (kg) | 12.93±1.89 | 28.47±1.09 |

| Adjusted fat thickness (cm) | 0.26±0.41 | 0.32±0.92 |

| Marbling score | 2 | 1 |

| Organoleptic evaluation | ||

| Color | 6.17±0.17 | 5.08±0.3 |

| Flavor | 6.25±0.17 | 5.75±0.11 |

| Juiciness | 6.92±0.2 | 6.25±0.17 |

| Texture | 5.83±0.1 | 5.67±0.1 |

| Tenderness | 6.08±0.24 | 5.25±0.25 |

| Overall palatability | 6.92±0.2 | 6.33±0.17 |

Mithun milk:

- Mithun milk composition and its comparison with other species has been characterized

- Developed value added milk products (paneer, lassi, dahi, and rasgolla)

| Particulars (%) | Mithun | Cow | Buffalo | Goat | Sheep | Yak | Human |

| Fat | 10.2 | 4.4 | 8.0 | 3.5 | 6.0 | 7.2 | 3.6 |

| Protein | 6.8 | 3.4 | 4.5 | 3.1 | 5.4 | 5.3 | 1.8 |

| Lactose | 4.6 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 4.4 | 5.1 | 5.0 | 6.8 |

| Total Solids | 21.6 | 12.6 | 17.4 | 11.0 | 16.5 | 17.5 | 12.2 |

| SNF | 11.4 | 8.2 | 9.4 | 7.5 | 9.5 | 10.3 | 8.6 |

| Ash | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.1 |

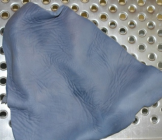

Mithun hide as a source of leather products:

- Mithun hides are consumed as a delicacy, among some tribes though it’s non-nutritious

- Mithunleather is soft and having better body and roundness, a potential raw materials for the leather industry

- Mithunleather is better than cattle leather

(Source-ICAR-NRCM Publication)

Diseases of Mithun and their control measures:

Parasites of Mithun

Ectoparasites:

Ticks cause huge economic losses as a result of injury, tick pyrexia, and tick paralysis, besides transmitting various pathogens including bacteria, viruses, and protozoan parasites to the host animals. The environmental conditions of the region greatly favor the survival and reproduction of ectoparasites leading to poor body conditions, reduced growth leading to decreased production performance of animals. In the seasonal study, the prevalence of Rhipicephalus microplus was highest in the summer season (Rajkhowa et al. 2005a; Chamuah et al. 2012). There has been also recording of Amblyommatestudinarium and Linognathusvituli, a sucking louse in mithun (Chamuah et al. 2016b). The tick, Ixodes ovatus and I. acutitarsus were also reported from Kohima district, which was identified based on the morphology of ticks and PCR amplification (Chamuah et al, 2016c). Leech infestation is also one of the common problems in mithun and causing respiratory death of the animals.

Nematodosis:

Gastrointestinal nematodiasis is a major problem encountered in mithun calves. The different gastro-intestinal helminths recorded are as follows Trichostronglylussp, Haemonchus sp. Mecistocirrus digitata, Toxocaravitulorum, Strongyloides papillosus, Bunostomumphlebotomun, Capillaria species, Oesophagostomum sp and Nematodirrus species (Chamuah et al. 2016 and Chamuah et al. 2017a). The Toxocaravitulorum, Strongyloides papillosus, Bunostmumphlebotomum, and Haemonchus contortusare the major causes of anemia and mortality in mithun calves. There has been evidence that parasitic gastroenteritis is directly or indirectly associated with mortality and morbidity in mithun (Rajkhowa et al, 2005b). Pimply gut condition is also commonly observed in mithun calves (Chamuah et al., 2016d). The soil type, pH, alkalinity, and type of pasture vegetation and nature of winds of a particular area influence the possibility of infection or existence of particular parasites in a locality. Moreover, grazing habitat as well as the periparturient rise of helminth infection in females influence the probability of infection. The occurrence of microfilaria is a very common phenomenon in mithun and Setariadigitata is the cause of this microfilariamia (Rajkhowa et al. 2005c; Chamuah et al. 2015c). The intensity of infection of microfilaraemia has been reported higher in older animals than in younger animals and prevalence higher in summer seasons due to more activity of culicoid flies.

Trematode and cestode infections in mithun:

The trematode and cestode infections are very common in mithun. Among trematodes, Fasciola gigantica, Paramphistomumepiclitum, Calicophorumcalicophorum, and Expalnatumexplanatum are common due to sharing of the life cycle with snails available in mithun rearing areas (Chamuah et al., 2016a). The occurrence of this trematode is always based on a suitable climate along with the presence of a snail intermediate host in the particular mithun inhabited area for completion of their life cycle. As per our extensive investigation, the prevalence of these parasites was more common in Arunachal Pradesh, and even clinical cases were also recorded in these areas. Among tapeworms Moneiziaexpansa and M. benideni, are commonly associated with potbelly condition and blockage of intestinal tract. Cystic echinococcosis caused by Echinococcusgranulosus and E. ortleppi was found to be highly prevalent in the mithun, with E. ortleppi being reported for the first time in mithun (Chamuah et al, 2016a).

Protozoal infection

Among tissue protozoa infection, coccidiosis is regarded as one of the commonly reported species with high morbidity in managemental conditions (Rajkhowa et al. 2004; Chamuah et al. 2013b). The common Eimeria species reported in mithun are Eimeria bovis, E. zuernii, E. ovoidalis, E. bukidonensis E. auburnensis, E. ellipsoidalis, E.subspherica and E. albamensis due to optimum climatic conditions for sporulation of oocyst. The prevalence of Eimerian species is generally higher in pre-monsoon than that in other seasons. Infestation with Eimeria species has been reported to be in all age groups of mithun. Comparatively, the pathogenicity has been observed to be always higher in young mithun. Toxoplasmosis is another tissue protozoan that affects most warm-blooded animals. However, there have been reports of serological prevalence in mithun inhabited in Nagaland and Mizoram (Rajkhowa et al. 2008; Chamuah et al., 2015b ). The prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii infection in mithun has been found to increase with the increase in age of the animal.

Microbial diseases of mithun

Mithun (Bos frontalis) like other livestock animal is susceptible to many microbial diseases. Prevention and control of disease in animal is of utmost importance as it can lead to tremendous loss to the farmer, and also many diseases can be spread between animals and human, which are then later transmitted to the latter. Microbial diseases are the ailment which is caused by either of the following- Bacteria, Viruses, Fungi and Protozoa. Common bacterial disease of Mithun includes Tuberculosis, Johne’s disease, Brucellosis, Hemorrhagic septiceamia, Colibacillosis, etc. Among the viral diseases, FMD is one of the most common and devastating disease, causing frequent outbreak in Mithun rearing community with huge economic impact. Other viral diseases like bovine viral diarrhea, blue tongue, Rota viral diarhhoea, Infectious bovine rhinotracheitis are also reported.

Prevention and control: Prevention of any diseases relies on the good managemental practices and treatment practice should be followed.

Vaccination: It is the most effective and efficient way to prevent the occurrence of any disease in the susceptible animals. The good vibe about vaccination can be highlighted by the global eradication of smallpox, which in the past was one of the most fearsome diseases. Also control of Polio by global vaccination campaign, which tremendously reduced the disease occurrence and its impact. In the animal sector, the same is shown by the eradication of Rinderpest from the country by vaccination. Currently, the FMD vaccine and other microbial diseases like HS, BQ, Brucellosis, etc are available. And people should aware that it is the best and effective way to control the disease before there is an uncontrolled outbreak which further requires extra care and treatment cost. Therefore, it is wise to vaccinate the animals against the disease (if the vaccine is available).

Biosecurity: Biosecurity in simple language means taking any precautions and measures to reduce the chances of an infectious disease being introduced onto the farm animals. Diseases can be introduced into a farm by people, animals, equipment, or vehicles. A good biosecurity measures reduces and mitigate the risk of the introduction of diseases to the animals and workers. Thus, to prevent the introduction of the disease to the farm, strict measures need to be implemented. Movement of man and animals should be restricted to a minimum; there should be no unauthorized entry at the farm. Farm duty personnel should follow good hygienic practices, sanitization and also farm tools and machinery should be routinely disinfected and cleaned. If any new animals are to be introduced to the farm, proper quarantine should be followed with a health examination before animals are allowed to enter the flock.

Segregation of sick animals: If animals are found sick, they should be separated and isolated from the healthy animals to minimize the chances of spread of disease to the healthy animals. Isolation of sick animals is also helpful in giving proper treatment and care and can prevent the animals from competing with food and resources with the healthy animals. The animals in the vicinity around the sick animals should be properly monitored for any signs of illness.

Reporting: It is very important to report and alarmed the veterinary personnel/local authorities in case of an outbreak of disease. Concealing the presence of disease in the animals is not helpful for any kind of outbreak, in fact, it may lead to a further devastating outbreak. It is suggestive to report any kind of disease at the earliest to minimize the spread of disease and its control.

Challenges and future prospects: The problems in control of disease in mithun largely depend on the system of rearing. Since the animals are reared in a free-range system, health care and management are of the difficult task. And since mithun are not included in the nationwide disease control program, the vaccine coverage is still low. And in many instances, the animals are found dead in the jungle before care can be taken. Therefore, it can be assumed that if proper health care management can be improvised at the time, the problems may be minimized. Maintenance of cold chain in handling and storing of vaccine is also a challenge. The genetic and molecular basis of the immune response against FMD infection and other microbial diseases in Mithun is largely unknown; even though mithun is considered to be sturdy and immunologically strong against many of the diseases. Hence, studies on the molecular level with regards to the immunity and its related gene/genes expression during the course of infection/vaccination may help in better understanding of the disease. In addition, a comparative study on the vaccine delivery system and the vaccine preparation will be helpful in formulating an effective vaccination strategy for mithun.

Metabolic and Non-Infectious diseases of Mithun:

There are reports of different non-infectious diseases recorded in mithun like as corneal opacity due to hypovitaminosis A, recurrent tympany, trichobezoars, anaemia, anorexia, debility, indigestion, diarrhoea, constipation, hepatic abscess, cough, pneumonia, arthritis, skin diseases, nervous disorders, and mastitis. Incorporation of vitamin A supplement along with other mineral mixture with sufficient green fodder in the ration of mithun is suggested for prevention of hypovitaminosis. Unilateral corneal opacity has also been reported in captive mithun (Rajkhowa et al., 2004). The condition can be effectively treated with enrofloxacin @ 5 mg / kg body weight for three days together with the instillation of ciprofloxacin eye drops twice daily for 14 days The incidences of metabolic diseases are not common in mithuns. However, in our farm condition, subclinical ketosis has been recorded in mithun. Specific dietary deficiencies of cobalt and possibly phosphorus may also lead to high incidence of ketosis (Radostits et al., 2000). This may be due in part to a reduction in the intake of total digestible nutrients (TDN), but in cobalt deficiency, the essential defect is failure to metabolize propionic acid into the TCA cycle. However, there was the record of detecting Ketone bodies in urine and milk samples of lactating mithuns (Report, 2005-06). In this case, there will be no need of extra treatment and control measure for the prevention of disease in mithun.

Health Calendar for better health and prevention of diseases:

Vaccination Schedule

| Disease Condition | Measures |

| TB | Double intra dermal test or Stormont test at six monthly interval and subsequent culling of the positive animals (when found positive in two consecutive tests) is suggested |

| JD

|

Johnin test at six monthly interval and subsequent culling of the positive animals (when found positive in two consecutive tests) is suggested |

| Brucellosis | Screening of the animals by Standard Tube Agglutination (SAT) test followed by segregation and culling of the positive reactors is suggested. |

| Calf Scour | Adoption of strict hygiene measures during first two weeks of life and treatment of clinical cases with gut antibiotics. |

| Pseudomonas Infection

|

Proper managemental measures of calves particularly during winter season like prevention from extreme cold and treatment of clinical cases with penicillin group of drugs is advocated. |

| Rota and Corona virus infection | Proper management, colostrums feeding immediately after birth and adoption of strict hygiene measures during first 2 weeks of age. |

| IBRT | Immediate segregation of the affected animal followed by antibiotic and sulfonamide treatment to reduce secondary bacterial infection. |

| Black Quarter | At six months of age by sub-cutaneous route followed by repeat dose every year before the onset of monsoon. |

| FMD | Polyvalent FMD vaccine with serotype O, A, and Asia1) at six month of age and repeat after that at every six months interval by sub-cutaneous route. Pregnant animals above 7 months of pregnancy should be avoided. |

| HS | Vaccination at six months of age by intramuscular route followed by repeat dose every year before the onset of monsoon. |

Control programme for parasitic diseases:

Parasitism is one of the hurdles in the improvement in the production performance of the animals. Therefore, the primary aim for controlling parasites is the right approach of treatment followed by a preventive strategy. The important factors to be considered before administering an anthelmintic are the health condition of the animal, type of parasitic infestation, dose, and route of drug administration. The use of Fenbendazole @10mg/kg body weight was found to be effective against moneiziasis in mithun. Similarly,Piperazine is the drug of choice against Toxocaravituloruminfection in mithun. The use of Piperazine has been reported to be more advantageous than that of Levamisole and Ivermectin due to early recovery in the treatment of ascariasis. The efficacy of Albendazole @15mg/kg body weight as broad-spectrum anthelmintics for mithun is well documented. Ivermectin @ 1ml/50kg body weight subcutaneously has been found to be very effective against both endo and ectoparasites (Chamuah et al., 2015a). The application of Cypermethrin as a spray for controlling Rhipicephalus microplus infestation is regularly practiced in the institute mithun farm. The comparative efficacy of some plant extracts on Rhipicephalus (Boophilus)microplus infestation in mithun in the Northeast has been documented (Chamuah et al.2013a; Dutta et al. 2018). Therefore, proper planning with the right execution of work leads to the success of parasite control in the near future.

List of commonly used anthelmintic for control of parasitic diseases:

| Sl. No. | Anthelmintic | Used against | Dose (mg or ml / kg body wt.) | Route |

| 1 | Tetramisole | Round worm | 7.5mg | S/C ly |

| 2 | Levamisole | Round worm | 7.5 mg | S/C ly |

| 3 | Pyrantel | Tapeworm | 10mg | Orally |

| 4 | Morantel | Broad spectrum | 10-20 mg | Orally |

| 5 | Benzimidazole group | Broad spectrum | 7-15 mg | Orally |

| 6 | Niclosamide | Fluke infestation | 90 mg | S/C ly |

| 7 | Oxyclozanide | Fasciolosis Amphistomiasis | 10mg | Orally |

| 8 | Triclabendazole | Fasciolosis | 9 mg | Orally |

| 9 | Ivermectin | Broad spectrum | 0.02ml | S/C ly |

| 10 | Doramectin | Broad spectrum | 0.02ml | S/C ly |

Acknowledgements: The Authors acknowledged to Director, ICAR-NRC on mithun, Nagaland for kind help.

Photo-credit Google

References:

Chamuah JK, Dutta PR, Prakash V, Raina OK, Sakhrie A, Borkotoky D, Perumal P, Neog R and Rajkhowa C. (2013a). Comparative efficacy of some plant extracts on Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus infestation in mithun (Bos frontalis) in the Northeast. J. Vet Parasitol, 27(1):5-7.

Chamuah, J. K., Raina, O. K., Lalrinkima, H., Jacob, S. S., Sankar, M., Sakhrie, A., Lama, S., Banerjee, P.S. (2016). Molecular characterization of veterinary important trematode and cestode species in the mithun (Bos frontalis) from north-east India. J. Helminthol 90(5)577: 82.

Chamuah, J. K., Singh, V., Dutta, P. R., Khate, K., Mech A. and Rajkhowa, C. (2012). Tick infestation in mithun. Indian Vet. J.. 89 (7): 140

Chamuah, J.K, Lama, S., Dutta, P.R., Raina, O.K. and Khan, M.H. (2016a). Molecular identification of Ixodid ticks of mithun from Nagaland. Indian J. Anim. Sci 86 (7): 762–763.

Chamuah, J.K., Bhattacharjee, K., Sarmah, P.C., Raina, O.K., Mukherjee, S. (2016b). Report of Amblyomma testudinarium in mithuns (Bos frontalis) from eastern Mizoram (India). J Parasit Dis 40(4):1217-1220.

Chamuah, J.K., Mech, A. and Perumal, P. and Dutta, P.R. (2015a). Efficacy of chemical and herbal anthelmintic drug against naturally infested gastrointestinal helminthiasis in mithun calves (Bos frontalis). Indian J. Anim. Res 49 (2): 269-272.

Chamuah, J.K., Pegu, S.R., Raina, O.K., Jacob, S.S., Sakhrie, A., Deka, A. and Rajkhowa, C. (2016c). Pimply gut condition in mithun (Bos frontalis) calves. J Parasit Dis 40(2):252-254.

Chamuah, J.K., Perumal, P., Singh, V., Mech, A. and Borkotoky, D. (2013a).Helminth parasites of mithun (Bos frontalis) -An overview. Indian J. Anim. Sci 83 (3): 235–237.

Chamuah, J.K., Raina, O.K., Sakhrie, A., Gama, N. (2017a). Molecular identification of Mecistocirrus digitatus and Toxocara vitulorum in the mithun (Bos frontalis) from north-east India. J Parasit Dis DOI 10.1007/s12639-017-0879-5.

Chamuah, J.K., Sakhrie, A., Khate, K., Vupru, K. and Rajkhowa, C. (2015b). Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in mithun (Bos frontalis ) from the northeastern hilly region of India. J Parasit Dis 39(3): 560–562.

Chamuah, J.K., Sakhrie, A., Lama, S., Chandra, S., Chigure, G.M., Bauri, R.K. and Siju, S., Jacob, S.S. (.2015c). Molecular characterization of Setaria digitata from mithun (Bos frontalis) Acta Parasitol., 60(3), 391–394; ISSN 1230-2821

Chamuah, J.K., Singh, V., Dutta, P.R., Khate, K., Mech, A., Rajkhowa, C. and Borkotoky, D. (2013b). Incidence of gastrointestinal helminths parasites in free-ranging mithun (Bos frontalis) from Phek district of Nagaland. Indian Vet. J. 90(3):127-128.

Dutta, P.R., J.K. Chamuah, J.K., Dowerah, R., M.H Khan, and Kumar, A.(2018). Acaricidal efficacy of certain herbal and chemical ectoparasiticides against Rhipicephalus microplus infestation in mithun (Bos frontalis).Int. J. Livestock.Res.,8(11):221-228

Rajkhowa S, Rajkhowa C, Bujarbaruah KM, Hazarika, GC. (2005). Seasonal dynamics of Boophilus microplus infesting the mithuns (Bos frontalis) of Nagaland. Indian J. Anim.Sci 75:25-26

Rajkhowa, S., Bujarbaruah, K.M., Kapenlo Thong and Rajkhowa, C. (2004). Prevalence of Eimerian species in mithuns of Nagaland. Indian Vet J 81: 573-574.

Rajkhowa, S., Bujarbaruah, K.M., Rajkhowa, C. and Thong, K. (2005a). Incidence of intestinal parasitism in mithun (Bos frontalis). Vet. Parasitol 19: 39-41.

Rajkhowa, S., Bujarbaruah, K.M., Rajkhowa, C., Hazarika, G.C. (2005b). Microfilaraemia in mithun (Bos frontalis) of Nagaland. Indian J. Anim. Sci., 75, 27-28.

Rajkhowa, S., Rajkhowa, C., Chamuah, J. (2008). Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii antibodies in free-ranging mithuns (Bos frontalis) from India. Zoonoses Public Hlth J. 55(6):320-322.

Report. 2005-2006. Annual Report for the year 2005-206. National Research Centre on Mithun,Jharnapani,Nagaland, India.

Thomas, N.S.R and Sastry, C.K. 1991. Livestock production management. Kalyani publisher, New Delhi.