Mitigating the Threat of African Swine Fever in Indian Pig Populations: A Comprehensive Risk Analysis and Adaptive Control Approach

Bhand Akshata Chandrakant1, Deshmukh Kaivalya Ruprao2 Ravi Mohan Shukla3

1PhD Scholar, Division of Medicine, Indian Veterinary Research Institute, Izatanagar, Bareilly – 243122. Email ID – drakshatavmc@gmail.com

2M.V.Sc Scholar, Division of Animal Biochemistry, Indian Veterinary Research Institute, Izatanagar, Bareilly – 243122. Email ID – kaivalya.deshmukh17@gmail.com

3M.V.Sc Scholar, Department of Veterinary Pathology, Veterinary College and Research Institute, Orathnadu, TANUVAS- 614625 Email ID- drshuklavpp@gmail.com

Abstract: African swine fever (ASF) poses a significant global threat to domestic and wild pig populations. In 2020, the first cases of ASF in domestic pigs were documented in Arunachal Pradesh and Assam, India, resulting in the demise of over 3700 pigs across 11 locations and causing substantial financial losses for small-scale livestock owners. This study examines the risk factors associated with ASFV transmission in the Indian context, identifying conserved elements in Indian geography that may contribute to future outbreaks. With no vaccine available, both domestic and wild pig populations, including wild boars and the endangered pygmy hogs, remain vulnerable to ASF. Implementing preventative measures is crucial to avoid catastrophic losses. The study explores adaptive control techniques tailored to the Indian context, aiming to reduce the risks of ASF transmission through an understanding of local circumstances. It presents a comprehensive risk-analysis methodology, contributing to the development of control plans and mitigation methods for the potentially disastrous effects of ASF in Indian pig populations. The findings underscore the need for ongoing vigilance and proactive measures to safeguard the pig farming industry and prevent further ASF spread in the region.

Keywords: African swine fever virus, epidemic, domestic pigs, risk assessment, and control measures

Introduction:

With morbidity and fatality rates approaching 100%, African swine fever (ASF) is a highly contagious viral disease brought on by African swine fever virus (ASFV) infection.( Wang N.et al.,2019) This disease was first reported in Kenya in 1921, and several important intercontinental transmissions have occurred since then (Eustace Montgomery R. et al.,1921). Because of ASF’s potential for transboundary spread and socioeconomic significance, the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) has designated it as a priority disease(OIE 2020) After being successfully eradicated in Europe in 1995, with the exception of Sardinia, ASF returned in 2007 and expanded to East Europe, where it posed a serious threat to both internal and international security(Montgomery et al.,1981) . ASF (African Swine Fever) is attributed to the African swine fever virus (ASFV) belonging to the Asfivirus genus. This virus is closely associated with a recently discovered asfarvirus called Abalone asfa-like virus within the Asfarviridae family [Blome et al.,2020]. (Domestic pigs and other members of the Suidae family, such as warthogs (Phacochoerus aethiopicus) and bushpigs, are susceptible to infection by the African swine fever virus (ASFV) [Cwynar et al.,2019] . The virus does not infect humans[Cwynar et al., 2019].ASFV is typically transmitted through contact with infected animals and fomites, the consumption of pig products contaminated with the virus, and bites from infected ticks.. However, ASFV transmission and maintenance varies substantially between countries. Direct transmission of ASFV can occur through (i) interaction between susceptible and infected pigs; (ii) eating meat from infected pigs; (iii) bites by infected soft ticks (Ornithodoros species); and (iv) indirect transmission through contact with fomites tainted by substances harboring viruses, including pigs’ blood, excrement, urine, or saliva [Penrith, M.L et al.,2009]. Multiple manifestations of clinical illness of ASF are possible, ranging from an asymptomatic infection to a peracute infection (with a death rate of less than 100%) [Blome et al.,2020]. A high temperature, anorexia, weakness, lethargy, recumbency, diarrhea, constipation, stomach discomfort, hemorrhagic indications, and other symptoms are often indicative of acute infections. Mortality after 6–13 days following the beginning of clinical symptoms, respiratory difficulty, nasal and conjunctival discharge, and abortions in pregnant women [Sanchez-Vizcaino et al.,2010]. Clinical indications of subacute infections, which include abortion, fever, and temporary bleeding with death or recovery within 2-4 weeks, are frequently associated with high mortality rates in young animals [Blome et al., 2020]. Clinical symptoms include low or intermittent fever, joint swelling, appetite loss, and depression that may appear over a period of two to fifteen months are linked to chronic infections, as are low death rates [Sanchez-Vizcaino et al.,2010].On May 21, 2020, Arunachal Pradesh and Assam, two northeastern (NE) states in India, notified to OIE the first ASF outbreak in their domestic pig populations [OIE]. The Northeastern area of India has international borders with China, making ii Unique geographical location. Transboundary emerging diseases are a persistent danger to Bhutan, Bangladesh, and Myanmar due to their porous borders [Barman et al.,2016]. In Northeast India, in addition to the initial ASF epidemic, there have been reports of numerous additional pig illnesses appearing in this area, including porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome [Rajkhowa et al., 2015] and infections with porcine circovirus-2 [Mukherjee et al., 2018].

The Natural Reservoirs and Etiology of ASF: The sole species in the genus Asfivirus of the family Asfarviridae is the African swine fever virus (ASFV), which causes swine fever (ASF) (https://ictv.global/report/).

Etiology of Viruses: Double stranded DNA makes up the bulk of the ASF virus (ASFV).The illness is complicated and diverse because to the presence of numerous ASFV genotypes and serotypes. (Dixon et al., 2013)

Transmission and Vector Involvement:

Direct contact between susceptible and infected pigs is the main method of transmission.

Contaminated food, tools, clothes, and automobiles can all contribute to indirect transfer.

Particularly in some areas, soft ticks belonging to the Ornithodoros genus are very important to the cycle of transmission. (Guinat et al.,2016)

Natural Reservoirs:

Wild animals, especially deer, serve as natural repositories for arsenic stain (ASF). They have the ability to transport and disseminate the virus, which adds to its environmental persistence. Soft ticks (Ornithodoros spp.) are thought to be ASFV’s natural vectors and reservoirs. (Mur, L et al.,2012)

Population Density of Domestic Pigs:

Pigs are one of the livestock species that is vital to the Indian economy since they not only help the rural masses secure a means of subsistence, but they also raise the socioeconomic standing of marginal farmers and the weaker segments of society [NRC Pig]. The majority of the population in the northeastern (NE) area of India is tribal, and raising pigs in backyards is an essential aspect of their way of life [Talukdar et al., 2019]. Pig farming has been reported in a number of states outside of Northeast India, including the mainland, particularly among the underprivileged and tribal populace in states like Jharkhand, West Bengal, and Uttar Pradesh, as a side business in the backyard [Sahu et al., 2018]. The state of Assam has the largest pig population, with 9.06 million (M) as per the most recent livestock census report (2019). Pathogens 2020, 9, 1044 4 of 18 (2.10 M), Jharkhand (1.28 M), West Bengal (0.54 M), Meghalaya (0.71 M), and Chhattisgarh (0.53 M) came next [Livestock Census 2020]. More than 70% of pigs raised in India are descended from native breeds [dahd.nic.in.]. Studies on infectious illnesses and group sizes have shown that larger, denser groups are associated with greater prevalence outbreaks of any disease [Nunn et al., 2015]. Averaging two to three native or crossbred pigs for fattening with zero to little family work and feeding inputs is typical for the majority of marginal households engaged in backyard farming [Kumar et al., 2007]. Pig owners, particularly those from isolated and rural areas, are seen to be very interested in small-scale pig farming (10–15 pigs per family), mostly in order to find ways to supplement their income and save money for their children’s futures. education and healthcare provided in accordance with the resources available locally [Chauhan et al., 2016]. The rural homes are connected to one another, even if the pigs kept in these areas are kept in smaller groups, making the animals more susceptible to contagious animal illnesses and their transfer to other animals.

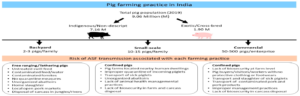

Figure1: Risk of African swine fever transmission associated with different pig farming practice in India

Risk assessment

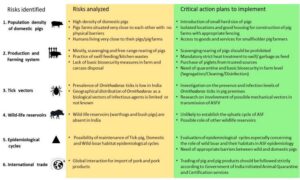

Figure outlines the important risk control strategies to lessen or eliminate the possibility of future establishment of ASF in India, together with the mentioned risk factors or indications.

Figure2: Critical action plans to stop future outbreaks of African swine disease, together with risk assessment and identification

Prevention and control:

1) Bio-security Procedures: Strict quarantine regulations should be put in place in order to stop the spread of ASF across pig populations. Limit the flow of people, cars, and animals into and out of pig farms. Sanitation and Disinfection: To reduce the danger of viral transmission, make sure that vehicle, equipment, and facilities are cleaned and disinfected properly.

2) Wildlife Management: Since wild boars can serve as viral reservoirs, control and manage wild boar populations.

3) Monitoring: Early Detection: To detect ASF outbreaks early, put in place reliable surveillance systems. This includes keeping an eye on clinical indicators, testing often, and reporting any suspected instances right once. Enhanced laboratory capabilities are necessary to provide prompt and precise diagnosis of ASF. This might entail setting up a network of diagnostic labs, supplying the required tools, and educating the workforce.

4) Immunization (if accessible): Vaccine Development: Make research and development expenditures for safe and efficacious vaccinations against ASF. One of the most important things in both avoiding and treating the illness is vaccination. Immunization Schedules: Establish targeted immunization efforts if a vaccine is made available, particularly in high-risk areas or places where ASF outbreaks have already occurred.

5) Public Education and Awareness:

Training Programs: Provide instruction on ASF prevention, clinical sign recognition, and appropriate bio-security procedures to farmers, veterinarians, and other stakeholders.

Campaigns for Communication: Start public awareness efforts to inform people about the dangers of ASF, the significance of reporting ill pigs, and the necessity of following bio-security protocols.

6) Global Cooperation: Information Exchange: Work together to exchange information and coordinate efforts to stop the spread of ASF with international organizations, nearby nations, and global health agencies.

7) Trade Restrictions: To stop the virus from unintentionally spreading across borders, enact and follow international trade laws pertaining to ASF.

Conclusions:

India’s ASF most likely got its start in a neighboring nation that borders India. Molecular evolutionary research and genetic characterization are being conducted to identify the progenitors of the current outbreak. In India, ASF outbreaks have resulted in approximately 3700 dead pigs in afflicted districts, according to a recent OIE announcement [https://www.oie.int/wahis_2/public/wahid.php/Reviewreport/Review?page_refer=MapFullEventReport&reportid=34283]. The animal husbandry departments of the Indian states of Arunachal Pradesh and Assam are now revising the present statistics and data about the number of pigs who perished as a result of the disease, and they will update them shortly. Controlling ASF is difficult in India because there is a need of a well-functioning traceability system for animals and a well structured veterinary apparatus. As a result, it is important to give careful thought to the risk factors listed and to reevaluate each one locally. Following the implementation of immediate containment measures to manage the illness, a comprehensive study strategy on monitoring and sero-epidemiology of ASF on domestic and wild pig populations should be established. To assess these dangers more precisely in the context of India, research on the role of biological vectors in the persistence and spread of ASFV is also crucial.

References

1) Wang, N.; Zhao, D.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.; Gao, Y.; Li, F.; Wang, J.; Bu, Z.; Rao, Z.; et al. Architecture of African swine fever virus and implications for viral assembly. Science 2019, 366, 640–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

2)Zhao, D.; Liu, R.; Zhang, X.; Li, F.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Wu, X.; et al. Replication and virulence in pigs of the first African swine fever virus isolated in China. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2019, 8, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

3) OIE. OIE-Listed Diseases, Infections and Infestations in Force in 2020. 2020. Available online: https: //www.oie.int/en/animal-health-in-the-world/oie-listed-diseases-2020/ (accessed on 13 August 2020).

4) Penrith, M.L.; Vosloo, W. Review of African swine fever: Transmission, spread and control. J. S. Afr. Vet. Assoc. 2009, 80, 58–62. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

5) Montgomery, R.E. On a form of swine fever occurring in British East Africa (Kenya Colony). J. Comp. Pathol. Ther. 1921, 34, 159–191. [CrossRef]

6) Blome, S.; Franzke, K.; Beer, M. African swine fever—A review of current knowledge. Virus Res. 2020, 287, 198099. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

7). Cwynar, P.; Stojkov, J.; Wlazlak, K. African swine fever status in Europe. Viruses 2019, 11, 310. [CrossRef]

8)Matsuyama, T.; Takano, T.; Nishiki, I.; Fujiwara, A.; Kiryu, I.; Inada, M.; Sakai, T.; Terashima, S.; Matsuura, Y.; Isowa, K.; et al. A novel Asfarvirus-like virus identified as a potential cause of mass mortality of abalone. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–12.

10)Sanchez-Vizcaino, J.M. Early detection and contingency plans for African swine fever. In Compendium of Technical Items Presented to the OIE World Assembly of Delegates and to OIE Regional Commissions; World Organization for Animal Health: Paris, France, 2010; pp. 129–168.

11)Walczak, M.; Zmudzki, J.; Mazur-Panasiuk, N.; Juszkiewicz, M.; Wo´zniakowski, G. Analysis of the Clinical ˙Course of Experimental Infection with Highly Pathogenic African Swine Fever Strain, Isolated from an Outbreak in Poland. Aspects Related to the Disease Suspicion at the Farm Level. Pathogens 2020, 9, 237. [CrossRef]

12)OIE.African Swine Fever, India. 2020. Available online: https://www.oie.int/wahis_2/public/wahid.php/ Reviewreport/Review?page_refer=MapFullEventReport&reportid=34283 (accessed on 27 October 2020).

13) Barman, N.N.; Bora, D.P.; Khatoon, E.; Mandal, S.; Rakshit, A.; Rajbongshi, G.; Depner, K.; Chakraborty, A.; Kumar, S. Classical swine fever in wild hog: Report of its prevalence in northeast India. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2016, 63, 540–547. [CrossRef]

14)Rajkhowa, T.K.; Jagan Mohanarao, G.; Gogoi, A.; Hauhnar, L.; Isaac, L. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) from the first outbreak of India shows close relationship with the highly pathogenic variant of China. Vet. Q. 2015, 35, 186–193. [CrossRef]

15)Mukherjee, P.; Karam, A.; Barkalita, L.; Borah, P.; Chakraborty, A.K.; Das, S.; Puro, K.; Sanjukta, R.; Ghatak, S.; Shakuntala, I.; et al. Porcine circovirus 2 in the North Eastern region of India: Disease prevalence and genetic variation among the isolates from areas of intensive pig rearing. Acta Trop. 2018, 182, 166–172. [CrossRef]

16)NRC Pig. National Research Station in Pig. Vision 2030. 2011. Available online: http://www.nrcp.in/pdf/ NRCP_vision_2030_protected.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2020).

17)Talukdar, P.; Talukdar, D.; Sarma, K.; Saikia, K. Prospects and Potentiality of Improving Pig Farming in North Eastern Hill Region of India: An Overview. Int. J. Livest. Res. 2019, 9, 1–14. [CrossRef]

18) Kumar, R.; Prakash, N.; Naskar, S. Livestock management practices by the small holders of north eastern region. Indian J. Anim. Sci. 2004, 74, 882–886.

19) Jeyakumar, S.; Sunder, J.; Kundu, A.; Balakrishnan, P.; Kundu, M.S.; Srivastava, R.C. Nicobari pig: An indigenous pig germplasm of the Nicobar group of Islands, India. Anim. Genet. Resour./Resourc. Génét. Anim. 2014, 55, 77–86. [CrossRef]

20)Chauhan, A.; Patel, B.H.M.; Maurya, R.; Kumar, S.; Shukla, S.; Kumar, S. Pig production system as a source of livelihood in Indian scenario: An overview. Int. J. Sci. Environ. Technol. 2016, 5, 2089–2096.

21)Sahu, S.; Sarangi, A.; Gulati, H.K.; Verma, A. Pig farming in Haryana: A review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 7, 624–632.

22)Livestock Census. 20th Livestock Census. All India Report. 2019. Available online: http://dahd.nic.in/ division/provisional-key-results-20th-livestock-census (accessed on 1 September 2020).

23) dahd.nic.in. Department of Animal Husbandry, Dairying. Government of India. Ministry of Fisheries, Animal Husbandry and Dairying. Available online: http://dahd.nic.in/sites/default/filess/NAP%20on% 20Pig%20.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2020).

23) dahd.nic.in. Department of Animal Husbandry, Dairying. Government of India. Ministry of Fisheries, Animal Husbandry and Dairying. Available online: http://dahd.nic.in/sites/default/filess/NAP%20on% 20Pig%20.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2020).

24)Nunn, C.L.; Jordán, F.; McCabe, C.M.; Verdolin, J.L.; Fewell, J.H. Infectious disease and group size: More than just a numbers game. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2015, 370, 20140111. [CrossRef]

25)Kumar, A.; Staal, S.J.; Elumalai, K.; Singh, D.K. Livestock sector in north-eastern region of India: An appraisal of performance. Agric. Econ. Res. Rev. 2007, 20, 255–272. 42. Patra, M.K.; Begum, S.; Deka, B.C. Problems and prospects of traditional pig farming for tribal livelihood in Nagaland. Agric. Econ. Res. Rev. 2014, 14, 6–11. 43. Singh, N.M.; Singh, S.B.; Singh, S.K. Small Scale Pig Farming in Manipur, India: A Studyon Socio-Personal and Socio-Economical Status of the SmallScale Tribal Farming Community. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2019, 8, 1158–1168. [CrossRef]

26)Dixon, L. K., Sun, H., Roberts, H., & Lundgren, M. (2019). African swine fever. Antiviral research, 165, 34-41.

27)OIE – World Organisation for Animal Health. (2020). Terrestrial Animal Health Code: African swine fever. Retrieved from https://www.oie.int/en/what-we-do/standards/codes-and-manuals/terrestrial-code-online-access/

28)FAO – Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2017). African swine fever: Detection and diagnosis – A manual for veterinarians. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/3/a-i7341e.pdf