Neoplasia of the Gastrointestinal System in Cattle

Navrose Sangha1 and Barinder Singh2

1Assistant Professor, Department of Veterinary Pathology , Khalsa College of Veterinaryand Animal Sciences , Amritsar, Punjab, India

2Graduate Assistant, Department of Veterinary and Animal Husbandry Extension Education , Khalsa College of Veterinary and Animal Sciences , Amritsar, Punjab, India

INTRODUCTION

Contrary to other species, neoplasia of the gastrointestinal system in cattle is uncommon (Theilen and Madewell, 1979). 0.003% of the 1.3 million cattle killed in Great Britain had tumours in the digestive tract, the bulk of which were liver and biliary tract carcinomas. In the gastrointestinal tract alone, just three tumours (0.00023%) were found (Anderson and Snadison, 1969). The percentage of gastrointestinal neoplasms in all bovine neoplasms, excluding liver neoplasms, ranges from 1.0% to 8.4%.The unusually young mean age of commercially butchered cattle may be a contributing factor in the low reported incidence of total neoplasia in cattle (0.3 percent in the United States), compared to other domestic animals and humans. Intestinal neoplasms may be more prevalent in an older cattle population. Bovine gastrointestinal neoplasia incidence is significantly influenced by geography. According to epidemiologic data, the bovine papillomavirus and local environmental carcinogens may have a mutagenic effect in some tumours (Jarrett et al., 1978).

NEOPLASMS OF THE ESOPHAGUS AND FORESTOMACHS

Papillomas, fibropapillomas, squamous cell carcinomas, and one lipoma have all been observed in the oesophagus. Papillomas, fibropapillomas, squamous cell carcinomas, lymphosarcomas, fibromas, and an unidentified connective tissue tumour have all been recorded in the fore stomachs (most frequently the rumen) (Jubb et al., 1985).

Papilloma, Fibropapilloma, and Squamous Cell Carcinoma

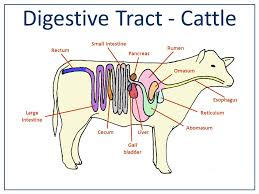

Cattle have keratinized squamous epithelium lining their oesophagus and fore stomachs (rumen, reticulum, and omasum), which makes them prone to the development of these tumours. Due to their limited geographic distribution and relationship with particular risk factors, these gastrointestinal tumours are peculiar to cattle. As a carcinogen model system, the relationship between the incidence of these tumours and particular clinical symptoms, oral exposure to an environmental carcinogen, and the presence of a papillomavirus has been investigated.

In the N asampolai Valley of Kenya, as well as in northern England and upper Scotland, papilloma and squamous cell carcinoma of the oesophagus and forestomachs of cattle are relatively prevalent. In Kenya, 6% of all cattle had upper alimentary papillomas, whereas in northern England and higher Scotland, 19% of all cattle had them. These rates indicate a distinct geographic frequency of disease and are higher than the 0.3% reported for the sum of all kinds of neoplasia discovered in cattle slaughtered in the United States. In these regions, ruminal squamous cell carcinoma, intestinal cancer, and urinary bladder neoplasia (chronic enzootic hematuria) are all linked to the prevalence of papillomas in the upper digestive tract of cattle. 2.5% of killed cattle in Kenya had ruminal squamous cell carcinoma. In comparison to 6% of the general population, 50% of patients had concurrent ruminal or esophageal papillomas. In northern England, ruminal or esophageal papillomas were present in 96% of cattle with ruminal squamous cell carcinoma compared to 19% of the general population. It’s possible that there is a connection between these two conditions given the elevated prevalence of papillomas in these cattle and the noticeably higher prevalence of papillomas found in squamous cell carcinoma. These papillomas have shown histologic alterations that have been regarded as carcinoma in situ and may be a prelude to malignant development into squamous cell carcinoma. Because bracken fern has infested the grazing regions, there is a higher prevalence and correlation of upper alimentary papillomas and squamous cell carcinomas in these places. Consumption of bracken fern is carcinogenic and can cause tumours in lab animals as well as bladder tumours in cattle (chronic enzootic hematuria). In humans, it is linked to esophageal cancer. Chronic bracken fern poisoning may inhibit the immune system and cause mutations. However, oral ingestion of bracken fern has not been shown to cause gastrointestinal cancer in cattle. The frond-type squamous papillomas in the upper digestive system of cattle are caused by the bovine papillomavirus (BPV-4), which has been isolated from these tumours. This kind of papilloma resembles the apillomas that can be found on the tongue, palate, and pharynx of cattle in appearance.

There is no underlying fibroma and only the surface keratinocytes of the frond-type papilloma are altered. According to Campo et al. (1980), BPV-4 is purely an epitheliotrophic virus. It’s possible that the immunosuppressive and mutagenic properties of bracken fern interact with the oncogenic BPV-4 virus to cause the papillomas to develop into squamous cell carcinomas. Additionally, 10% of Kenya’s ruminal squamous cell carcinomas had herpesvirus particles. Other causes of ruminal cancer, such as spontaneous transformation, other viral agents, mechanical irritation, and interaction with other carcinogens, must be taken into account in the sporadic case, particularly in a nonendemic area. Transformed bovine fibroblasts that proliferate to form solid masses with overlaying epithelium make up upper alimentary fibropapillomas. Contrary to papillomas, only cases of fibropapillomas in the oesophagus, ruminoreticular groove, and rumen have been reported. These make up 22% of the squamous papillomas and fibropapillomas found in cattle’s upper digestive tracts. These altered fibroblasts contain the genome of the bovine papillomavirus-2 (BPV-2; bovine skin papillomavirus). However, since the granular layer of the epidermis does not exist in the digestive system, complete viral replication with antigen expression must take place there. Therefore, BPV-2 infection in the digestive tract may be a process that ends in fibroblast transformation rather than continuing the infection with viral replication. Fibropapillomas have not been the source of BPV-4 isolation.

Fibroma

Two cows were found to have single, massive (> 15 cm), multilobulated fibromas in the ruminorecticular groove, close to the cardia (Bertone et al., 1985). These aggregates have squamous epithelial surfaces and whorls of well-differentiated fibrocytes, according to histology. These lesions’ origin was not determined.

Cattle rumen and reticulum lymphosarcoma has been documented as a local extension of abomasal lymphosarcoma or as a distinct focus of systemic lymphosarcoma. Infiltration of the abomasum and other more frequently affected organs occurred concurrently with infiltration of the forestomachs in every case recorded. Between 1977 and 1983, six cattle necropsied at Cornell University were found to have lymphosarcoma of the forestomachs (9% of all lymphosarcoma cases and 0.4% of calves necropsied). However, in the European publications, lymphosarcoma is not identified as a tumour of the alimentary tract in cattle. This may reflect the prevalence of the adult (multicentric or enzootic) form of the disease in the United States compared to the sporadic form of the disease that is more frequently documented in Europe. According to Ferrer (1980), the cause of forestomach lymphosarcoma is thought to be the transformation of lymphoid cells by the bovine leukaemia virus.

Clinical Signs, Diagnosis, and Treatment

Small papillomas in the rumen or oesophagus are frequently unintentional. Larger esophageal masses may cause dysphagia and obstruction. The inhabitants of Kenya’s Nasampolai Valley refer to the usual clinical presentation of larger papillomas, squamous cell carcinomas, or fibromas that develop close to the cardia or ruminoreticular groove as “embonget”. Eructation and rumination are occasionally hindered by the position of these aggregates. Intermittent ruminal tympany, ruminal impaction, and inappetence are some of the clinical symptoms. Endoscopy through a rumenotomy incision was used to observe the passage of the pedunculated fibromatous mass into the distal oesophagus during eructation in one cow. Transnasal or transoral esophageal endoscopy could provide a conclusive diagnosis of esophageal tumours. Although particular treatment for this issue has not been described to the author’s knowledge, it may involve laser therapy administered under endoscopic guidance or surgical removal using a snare. If some tumour tissue could be acquired for the creation of vaccines and ruminal tympany was diverted by a rumenostomy, immunotherapy would be beneficial or complementary. Bracken fern is one example of a potentially carcinogenic substance that needs to be eliminated from the diet and environment. The diagnosis of forestomach neoplasia was made via a necropsy or rumenotomy. If additional diagnostic procedures (such as abdominal radiographs, peritoneal fluid analysis, complete blood count, serum biochemistry profile) are normal, abdominal exploration and subsequent rumenotorpy may be chosen.

If the ruminal masses are at the cardia, they may be visible or even palpable through the rumenotomy incision. At necropsy, multiorgan involvement and stomach lymphosarcoma are frequently found. The forestomachs were not the primary focus of clinical signs or diagnostic techniques in the few documented cases. Surgical excision is used to treat fibropapillomas, fibromas, and accessible papillomas in the forestomas. Single ruminal fibroma excision has a promising outlook. Due to the concurrent involvement of other organs, the prognosis for forestomach lymphosarcoma is poor (Bertone, 1990).

Any other mechanical esophageal blockage or vagal condition would be on the differential diagnosis list for esophageal or stomach tumours. The causes of vagal syndrome include advanced pregnancy, idiopathic reticuloruminal atony, traumatic reticuloperitonitis, reticular adhesions, reticular abscess, a perireticular space-occupying mass (such as lymphosarcoma, omental fat necrosis), abomasal impaction, and inflammatory conditions that would affect the vagal nerve (peritonitis).

References

Anderson, L. J., & Snadison, A. T. (1969). A British abattoir survey of tumours in cattle, sheep and pigs. Veterinary Records, 84, 547.

Bertone, A. L. (1990). Neoplasms of the Bovine Gastrointestinal Tract. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice, 6(2), 515-524.

Bertone, A. L., Roth, L., & O’Krepky, J. (1985). Forestomach neoplasia in cattle: A report of eight cases. Comp Cont Educ Pract Vet 7, 585.

Campo, M. S., Moar, M. H., & Jarrett, W. F.H. (1980). A new papilloma virus associated with alimentary cancer in cattle. Nature, 286, 180-185.

Ferrer, J. (1980). Bovine lymphosarcoma. Comp Cont Educ Pract Vet, 2, S235.

Jarrett, W. F. H., McNeil, P. E., & Grimshaw, W. T. R. (1978). High incidence area of cattle cancer with a possible interaction between an environmental carcinogen and a papilloma virus. Nature, 274, 215-217.

Jubb, K. V.F., Kennedy, P. C., & Palmer, N. (1985). The alimentary system. In Jubb, K. V. F., Kennedy, P. C., & Palmer, N. (eds): Pathology of Domestic Animals. New York, Academic Press, pp36, 37, 49, 85, 87, 89.

Theilen, G. H., & Madewell, B. R. (1979). Tumors of the digestive tract. In: Theilen, G. H., & Madewell, B. R. (eds): Veterinary Cancer Medicine. Philadelphia, Lea & Febiger, pp 315-319.