by-DR.Deependra Singh Shekhawat.

RPM, Stellapps Technologies Pvt.ltd.

Milk fever (Parturient Paresis) or hypocalcaemia is a preventable disorder in lactating beef and dairy cows. About five to eight percent of cows get milk fever, making it a common, but hopefully unlikely, problem in your herd.

Although certain breeds are more susceptible to milk fever than others, such as the Jersey and Guernsey dairy breeds, any female bovine may exhibit signs of milk fever. It is important to know the signs and symptoms of milk fever as well as the potential causes, so you can both prevent it and treat cows that exhibit symptoms of this sometimes-fatal disease.

What Is Milk Fever?

Milk fever refers to a set of symptoms that commonly occur when calcium levels in a cow’s bloodstream drop too low. It can happen before, during or shortly after she gives birth to a calf. If signs appear after she gives birth to her calf, they will usually manifest within 72 hours after the birth is complete.

Farmers have known about milk fever for centuries, but it wasn’t until around 1925 that the cause was identified as a calcium imbalance in the blood stream. Cows begin producing milk prior to giving birth in preparation for the calves’ first hours of life. The first flush of milk released to the nursing calf contains colostrum, a nutrient-rich milk that sustains and boosts the calves’ immune system.

About 80 percent of milk fever cases occur after calving, especially among dairy cows. Cows that produce high volumes of milk are most susceptible to milk fever because their bodies can’t replace the calcium lost to milk production quickly enough.

Colostrum in dairy cows can contain 20 to 30 grams of calcium. To continue producing milk, the cow must continue drawing calcium from her own system. Colostrum production causes calcium levels in the cow’s bloodstream to drop from 8.5–10 mg/dL to <7.5 mg/dL.

If the cow does not have access to calcium-rich pasture during this critical period or if she has already given birth to several previous calves, her body may not have enough calcium stores to support her during lactation. When calcium levels drop below acceptable levels, the cow’s nervous system and muscles are affected. The resulting symptoms are called milk fever.

Milk fever may also be caused by other factors. An imbalance in the minerals available to lactating cows may cause milk fever. Milk fever can also be exacerbated by an infection — such as in the udder, reproductive system or digestive system.

Stages and Symptoms of Milk Fever

Most cow owners notice the symptoms of milk fever when their cows enter Stage Two. The symptoms differ at each stage of the disease.

• Stage 1: Stage 1 lasts only for about an hour, and the signs of milk fever can be easy to miss. During Stage 1, the cow may shift her weight repeatedly from one side to another. She may act nervous or be very excitable or spooky. Cows lose their appetite and may seem weak.

• Stage 2: Stage 2 is when many owners first detect a problem with their cows. This stage can last from one to 12 hours. The cow may stretch her head out or turn it toward her flank repeatedly. She will likely seem very weak and lethargic. Her heart rate speeds up as well, often past 100 beats per minute, and her temperature may drop — a normal cow’s temperature should be around 101.5 degrees F. Cows experiencing milk fever will have a decreased temperature between 96 degrees F and 100 degrees F. Because the low calcium levels affect muscle contractions, she may also be constipated. Her nose may be dry and cold and the ears may be cold, too. She’ll have trouble walking and may stagger.

• Stage 3: Stage 3 means that milk fever has progressed to the point where if treatment is not given quickly, the cow may die. The heart rate speeds up to 120 beats per minute, and at this point, the cow will lie down, or may fall down, and will likely become comatose.

Owners can recognize milk fever by watching for the following signs:

• Check pregnant and lactating cows frequently, especially during the 24 to 72-hour period following calving.

• Watch for signs of distress, lethargy, muscle twitching, constipation or uncoordinated gaits.

• Take your cow’s rectal temperature if you suspect milk fever. The normal temperature is 101.5 F. Anything lower than this may signal milk fever. Temperatures higher than this may indicate an infection from calving in the udder, uterus or elsewhere.

• Take the cow’s pulse to determine heart rate. This can be tricky, especially if the cow is twitching from muscle contractions related to milk fever. The pulse can be detected along the face, where the facial artery crosses the cheekbone. Run your hand along the jawbone and cheek to find the pulse while a helper holds the cow still. Count the beats for 15 seconds, then multiply by four to get the beats per minute.

• A veterinarian should, immediately see downer cows, or cows that have fallen or lie down without being able to rise.

TREATMENT

The first step, if you suspect milk fever in any of your cattle, is to call your animal’s veterinarian. They can make the diagnosis of milk fever and administer an intravenous solution that contains calcium and other minerals, if necessary, to balance the ratios in the bloodstream.

The typical treatment for milk fever is to use 300 milliliters or more of a 40 percent solution of calcium borogluconate. Other solutions may include so-called “three in one” or “four in one” solutions that contain a mixture of minerals including calcium, magnesium, phosphorous and dextrose.

Some veterinarians prefer the combined solution. It replaces the missing calcium in the bloodstream, as well as adds other important minerals that may be lacking. The combination can help the cow recover quickly.

Although one 300 ml solution may be used, larger animals may require 600 ml. The solution must be administered slowly, but once she receives enough of the proper minerals, the cow should be on her feet quickly. She may be shaky and weak for a little while, but she should make a full recovery.

Some cows also require a subcutaneous (under the skin) administration of fluid. Fluids are usually not given orally. There is a risk of cows aspirating, or drawing fluid into the lungs, with this method. The preferred administration is by intravenous solution or subcutaneous administration.

This treatment is usually very effective if milk fever is caught in the early stages. Treatment during Stage 3 offers uncertain outcomes. Most cows can recover from milk fever, especially if it is caught in the early stages.

There are a few diseases/disorders in dairy cattle and buffaloes which occur for improper feeding and/ or nutritional management. Milk fever is one of such disorders which occurs due to faulty feeding practices during the pregnancy period and immediately after calving of dairy animals.

Milk fever is a disease of high producing dairy animals occurring within one or two days after calving. It is because of low calcium supply through feeds and hence the animal is unable to meet the demand of the body’s requirement for heavy drainage of calcium through milk. On an average, there is drainage of about 23 g of calcium for every 10 litres of colostrum produced just after calving. If this amount is added to the daily requirement during this period the need is about 10 times higher than the supply of calcium through feed. When feed-stuffs provided to the cows are unable to meet this requirement of needed calcium, milk fever develops. Milk fever develops when serum calcium drops below 6.5 mg/dl of blood from normal 8-10 mg/ dl of blood.

Milk fever can also be called the ‘gateway disease’ as it increases the risk of other diseases manifold such as mastitis, ketosis, retained placenta, displaced abomasum and uterine prolapsed.

Common observable symptoms in milk fever

1. Depression and unwillingness to move and eat.

2. The body temperature goes below normal and the extremities becomes cold.

3. The muzzle and nose become dry.

4. The eyes become dull and expressionless and the membrane covering the eye turn reddened.

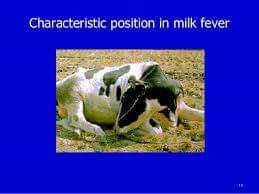

5. The animal lies with its head turned to one side for which the neck assumes an S shape.

6. The pulse and breathing become accelerated and very often breathing becomes laboured and accompanied by groaning.

7. There may be bloating i.e. accumulation of excessive gases in the rumen as the gut becomes paralysed.

8. The animal goes to coma and death may occur within a few hours.

Nutritional strategies to prevent milk fever

Occurrence of Milk fever has direct relationship with the feeding strategies followed during the pregnancy and immediately after calving. Thus, it is possible to prevent milk fever by adopting appropriate feeding strategies during the above mentioned periods. The following feeding strategies are suggested to prevent milk fever occurrence in high milk producing dairy cows.

Restriction of calcium in the prepartum (before calving) period

Calcium is an essential mineral required for a number of functions to sustain life of animals. As a preventive measure of milk fever, calcium should never be supplemented before calving. Dietary calcium level should also be low (intake should be around 20 g/day). Vitamin D helps in absorption of calcium from the digestive tract and significantly helps to prevent milk fever when given a week or so before calving. However, as the commonly fed forages and concentrates provide significant quantities of calcium, manipulation of ration to low calcium level is sometimes difficult practically to ensure low calcium intake. In such situation supplementation of zeolite and vegetable oils can be done as both are known to reduce the absorption of calcium sufficiently.

Magnesium supplementation

Magnesium is another important body element and 70% of body magnesium is found in bones. Magnesium is responsible for membrane stability and thus related with cardiac and skeletal muscle functions and nervous tissue function. It is also related with several enzymes required for body metabolism and most importantly plays very important role in calcium metabolism. Magnesium is essential for maintaining blood calcium level in animals thus indirectly responsible for occurrence of milk fever. Magnesium supplementation at the rate of 15 to 20 g/day along with a source of easily digestible carbohydrate helps in preventing milk fever in dairy animals. During pregnancy magnesium should be supplemented at the rate of 0.4% of dry matter of ration.

Supplementation of calcium to susceptible animal after calving

It is not advisable to use this method as a first line of prevention. Supplementation should be done depending on the quality of ration provided and level of calcium in it, as there are chances of negative effects for breaking of calcium homeostatic pathways in the body.

Manipulating the DCAD of ration

The DCAD i.e. dietary cation-anion difference of ration is directly related with incidence of milk fever. The DCAD of ration can easily be calculated if percentages of concentrations of sodium, potassium, chlorine and sulphur ions of the ration are known [DCAD = (Na + K) – (Cl + S)]. Cattle fed ration with a high DCAD tends to cause milk fever, whereas negative DCAD tends to prevent milk fever. Reduction of DCAD rather than calcium content of ration during prepartum (before calving) is considered as the method of choice for preventing milk fever. It is because feeding more concentrates or cereal silages to dry cows to lower calcium intake may be expensive and may predispose cows to other complications like fatty liver syndrome, ketosis, abomasal displacement for high energy density. The DCAD can be reduced by addition of anionic salts (i.e. salts of chloride, sulphur or phosphorus) to the ration of pre-calving cows. Usually typical ration of dairy cows has DCAD ranging from +100 to +200 meq/ kg dry matter (meq= milliequivalent i.e. one meq is equal to 1/1000th of equivalent weight).

Addition of anionic salts (minerals high in Cl and S relative to Na and K) or mineral acids to the ration lowers DCAD and reduces the incidence of milk fever. Addition of three equivalents of anions to 12 kg ration dry matter lowers DCAD by 250 meq/kg.

Other feeding suggestions

1. Just after calving, cow should not be milked completely for about 2-3 days. However, to avoid associated complication like mastitis, the calf should be allowed to suck milk for about 36 hours during this period.

2. Forages rich in calcium should not be fed before calving particularly during the last trimester of pregnancy period.

3. The following formulation can be suggested as a lick on feed: 1 cup molasses + 4 tablespoons linseed oil or meal + 2 tablespoons salt + 2 tablespoons causmag or dolomite.

4. It is important to restrict potassium (K) intake for dry cows to prevent milk fever.

Milk fever can be prevented through a variety of good animal husbandry practices. It is more common among dairy breeds, especially those known for high milk volume production. Jersey, Gurneys and other dairy breeds are more susceptible to milk fever than beef cattle, although no breed is immune to the problem.

If you plan to raise calves, the following steps should be taken to prevent milk fever:

• Maintain your pastures:

Cows get their calcium from the pasture grasses they eat. The calcium content of grasses varies according to the species of grass, the time of year, the amount of rainwater and the soil quality. Pay close attention to your pastures and follow a good routine of pasture care and maintenance that includes reseeding, fertilizing and resting fields from overgrazing.

• Feed a good diet: A mixture of pasture grass, good-quality alfalfa hay, minerals and calcium will keep your cows healthy. Adjusting cows’ feed for their health, such as adding more grass to a lactating cow’s diet and reducing feed for dry cows can also help keep them healthy.

• Feed minerals: Many cow owners offer free-choice mineral blocks. These are large blocks of condensed minerals, including calcium, placed where cows can lick them whenever they choose to do so. The idea is that cows will lick the blocks when they feel they need minerals. This works for beef cattle, but it may not be adequate for cows susceptible to milk fever. You may need to actively feed minerals, such as a sprinkling of dried or crushed minerals, including calcium and vitamin D, to these cattle. You can control the amount of minerals more easily with controlled feeding, too.

• Reduce calcium two weeks prior to calving: This sounds counter-intuitive, but Dr. Anna O’Brien, a large animal veterinarian, reports that reducing calcium intake about two weeks before your cow is expected to give birth may actually prevent milk fever. The sudden decrease in calcium conditions the cow to store calcium more readily and easily in the bones, so she’s able to replace her own body’s calcium after using it to produce milk for her calf.

• Don’t breed too often: Parturition and lactation take considerable energy from animals. Cows that have given birth to two, three or more calves are more susceptible to milk fever than first-time mothers.

• Consult an animal nutritionist: If all of this talk of minerals, forage and other nutritional aspects of caring for cows has you confused, you might want to consult with a nutritionist, agricultural scientist or veterinarian to better understand your cow’s nutritional needs and how you can meet them through the forages and grains you raise on your farm.

Most Cooperative Extension offices have an agricultural extension agent who is both skilled and knowledgeable about farming practices. In areas where raising beef and dairy cattle are the norm, there may even be a specialized ag agent just for the cattle industry. They can advise you on what you may need to do to prevent milk fever in your herd.

While it is true that milk fever is caused by low calcium, what other causes are there for the disease? Why do some cows in a herd come down with milk fever but other cows in the same herd do not? Why do cows on one farm, that may share the same genetics with cows on a neighboring farm, develop milk fever, but those on the second farm do not?

All cases of milk fever are caused by the unhealthy drop in the calcium levels in the bloodstream. Calcium in the blood is derived from calcium in a cow’s diet. Here is how that calcium ratio can be disrupted by dietary changes or choices:

• Corn: Corn is a traditional feed on many cattle and dairy farms, but it has its disadvantages. Silage, derived from corn, is often used as a winter feed, but heavy silage feeding, especially for dry (non-lactating cows) can set them up for milk fever.

• Grain: Grain feeding can also disrupt calcium levels. High grain feeding with little or no forage predisposes them to milk fever. So too can feeding dry cows too little grain with only forage and grass. A balanced mixture of grass, hay or forage, and grain leads to healthier cows.

• Low magnesium: The muscles and nervous system are impacted by the ratio and amount of both calcium and magnesium in the bloodstream. Too little magnesium can unbalance calcium levels, leading to milk fever. Corn silage, grass and small grains are low in magnesium. Feeding too much can create an imbalance.

• Age: Older cows may have difficulty absorbing nutrients through the rumen, the special digestive organ that helps them break down the nutrients in tough, fibrous grasses.

• Alkaline water: Water that is excessively alkaline, with a pH greater than 8.5, can actually make it more difficult for cows to absorb minerals.

• Toxemia: Certain organisms can contribute to the development of milk fever. These include organisms that cause coliform mastitis, and bacterial infections of the digestive or reproductive tracts.

The Prognosis After Milk Fever

The good news is that if you act fast enough, your cow should recover within just a few hours after the veterinarian treats her with intravenous or subcutaneous (under the skin) calcium, an alternative to an IV form of calcium. Downed cows will rise, and although they still may be shaky, they will often start to look for something to eat within minutes of successful treatment.

A cow that has had a bout of milk fever in the past may have one again, so you should talk to your veterinarian about any special steps to prevent milk fever in the future. Your cow’s veterinarian may recommend dietary changes, for example, or supplementation to prevent milk fever in the future.

How to treat milk fever

It is always advisable to call a Veterinarian when the animal is sick. Treatment by farmers based on the observable symptoms are not at all advisable. Remarkable success can always be expected if treatment is carried out properly. The following treatment strategies can be followed.

Treatment of Milk Fever

Treat cases of milk fever as soon as possible with a slow intravenous infusion of 8-12 g of calcium

Ensure the solution is warmed to body temperature in cold weather

Sit the cow up in a sternal recumbency position and turn her so that she is lying on the side opposite to the one on which she was found and turn every 2 hours

Massage the legs

Protect cases from exposed weather conditions

Remove the calf if a severe case

Treat relapse cases as above

• Intravenous injection of calcium borogluconate (20% solution) or other calcium salts. Special care is required while injecting calcium borogluconate so that it is not made under the skin or the solution does not enter the tissues surrounding the vein since this causes irritation which may result restraining of the animal difficult.

• No commercial oral preparation is available. But, for suffering cows which are still on their feet or have only just sat down and can still hold their heads up, an oral preparation can be suggested. The recipes of that oral preparation are as follows:

• Dissolve calcium chloride (around 150g, but not more than 200 g) in 200 ml of warm cider vinegar.

• After properly dissolving the calcium chloride, add around 150 ml of fish or vegetable oil.

• Then 50 g of causmag or dolomite should be added and the volume of the solution should be made up to 500-600 ml with molasses.

• The solution should be shaken thoroughly before feeding to the animal so that the vegetable oil is suspended well. Vegetable oil helps to protect intestinal mucosa from irritation due to calcium chloride.

• It is advisable not to give more than three treatments with this preparation as calcium chloride may cause stomach ulcers. If at all required calcium chloride should be replaced with lime flour.

Conclusion

The milk fever is not only economically important, but also it causes loss of animals as it occurs at the most productive period of a lactating cow. Economic loss due to milk fever happens because of reduction in quantity of milk as well as expenditure on treatment of disease-affected animal. As milk fever is a metabolic disease directly related with feeding management, adopting appropriate feeding strategy during the pregnancy period and immediately after calving can prevent the occurrence of milk fever. Feeding of proper balanced ration considering the factors predisposing milk fever will help the farmers to avoid this menace successfully.

Good Practice Based on Current Knowledge

Prevention of Milk Fever

A strategy to prevent milk fever in a herd will depend on herd-specific circumstances such as the attitude and skills of the farmer and the facilities available in the production system. Prevention of metabolic disease at calving should form an important part of an integrated herd health plan for the farm:

Do not breed from cows or sires with a history of recurrent milk fever

Prevent animals from becoming overfat (cows should calve at BCS 2.5-3) and ensure they get plenty of exercise

Make sure that the diet is sufficient in magnesium for cows in late pregnancy

Avoid stress in cows

Feed adequate long fibre to transition cows

Ensure that the calcium intake during the dry period is below 50 g/day

Ensure that adequate dietary calcium is available over the risk period (just prior to and after calving)

Try to avoid diets high in strong cations, such as sodium and potassium.

Source: Farm Magazine of Central Agricultural University