ONE HEALTH APPROACH: THE NEED OF THE HOUR

Dr. Diva Dhingra

M.V.Sc. 1st year , Dept. of Veterinary Surgery & Radiology ,COVSc. & AH ,NDVSU, Jabalpur

The fight against rabies poses both a tremendous task and an exceptional opportunity for communal action in a world dedicated to the concept of “One Health, Zero Death.” An ongoing hazard to public health, rabies is a viral disease that affects mammals and has repercussions for both humans and animals as well as ecosystems. Around 36% of the world’s annual rabies deaths are thought to occur in India, mostly as a result of young children coming into touch with infected dogs. Rabies is thought to kill about 55,000 people annually worldwide. The public’s health is significantly impacted by rabies despite it being a viral zoonotic illness that only affects mammals. Even if it is possible to prevent rabies, its prevalence is increasing daily, which is a concerning issue worldwide, including in developed and developing countries. Rabies is an endemic disease in nearly all land masses, with the exception of continents like Australia and Antarctica, where there have been no confirmed cases of dog-mediated rabies. Many Asian and African countries still suffer with the disease, despite the fact that rabies has been declared eradicated in many Asian, European, North, and South American countries. Bangladesh and India may have very extensive rabies outbreaks, although Nepal, Myanmar, Bhutan, Thailand, and Indonesia only have somewhat higher incidences of the disease. The Asian subcontinent’s countries are thought to be home to 0 to 55% of all canine rabies cases worldwide. The rabies virus spreads through the saliva of a wide range of animals, including humans. But most canine-related fatalities in humans happen when a person is bitten by or comes into contact with an infectious dog. Children under 15 make up between 30 and 60% of dog bite victims in countries where rabies is prevalent (endemic).

Rabies is an ancient disease that has been recognized since roughly 2300 BC. The Sanskrit word rabhas, which means to do violence, is the root of the word rabies. The word lyssa, which the Greeks derived and which has meaning “violent,” is utilized in the name of the genus that contains the rabies virus, Lyssavirus. A zoonotic illness, rabies is. It is a single-stranded RNA virus that is a member of the Rhabdoviridae family and the Lyssa virus genus.

We must first analyze the virus that causes rabies in order to comprehend the threat it poses. The rabies virus is a sophisticated pathogen with distinctive ways of infection, according to virology research. It is distinguished by its neurotropic nature, which targets the nervous system and makes it especially deadly. The intricacy of preventing the spread of the virus is highlighted by the complexity of managing its transmission, which is further highlighted by examining the routes of transmission and identifying common vectors, which are typically all mammals like dogs, cats, mongooses, and monkeys. The plague of rabies knows no boundaries; it exists everywhere. Examining the global spread and prevalence of rabies gives a bleak picture of its pervasiveness. The cost rabies exacts on people and animals, however, is what gives the disease its full gravity. A strong reminder of the disease’s destructive effects on lives and livelihoods is provided by the number of fatalities among humans and the financial losses suffered in the agriculture and veterinary industries.

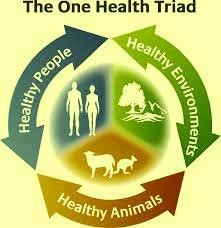

The term “One Health” was first used in 2003-2004, coined in response to the spread of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 and the emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in the early 2003. It was also used to refer to a set of strategic objectives known as the “Manhattan Principles,” which were developed at a meeting of the Wildlife Conservation Society in 2004 and recognized the connection between human and animal health as well as the dangers that diseases pose to the supply of food. These principles were a crucial step in realizing the critical importance of collaborative, cross-disciplinary responses to emerging and resurgent diseases, and in particular, for the inclusion of wildlife health as a crucial part of global disease prevention, surveillance, control, and mitigation. The outbreak of SARS, the first serious and easily spreadable novel disease to appear in the twenty-first century, made it clear that (a) a previously unidentified pathogen could materialize from a wildlife source at any time and in any location and, without notice, threaten the health, well-being, and economies of all societies, and (b) there was a clear requirement for countries to have the capability and capacity to maintain an effective alert and response system to detect and swiftly redress any such threat (c) Using the fundamental tenets of One Health, global participation and cooperation are required to respond to significant multi-country outbreaks or pandemics. One World, One Health, and finally One Health are all variations of the idea of One Health, which has been around for at least two hundred years. Many definitions of one health have been put out, but there isn’t a single one that is universally accepted. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the One Health Commission agree on the following definition as being the most popular: ‘One Health is defined as a collaborative, multisectoral, and transdisciplinary approach—working at the local, regional, national, and global levels—with the goal of achieving optimal health outcomes recognizing the interconnection between people, animals, plants, and their shared environment’. According to the One Health Global Network, a definition is: ‘One Health recognizes that the health of humans, animals and ecosystems are interconnected’. The One Health Institute at the University of California at Davis offers a far more basic version.: ‘One Health is an approach to ensure the well-being of people, animals and the environment through collaborative problem solving—locally, nationally, and globally’.

The One Health concept clearly focuses on consequences, responses, and actions at the animal-human-ecosystems interfaces, and especially (a) emerging and endemic zoonoses, the latter of which are responsible for a much greater burden of disease in the developing world and have a significant social impact in resource-poor settings antimicrobial resistance (AMR), as resistance can develop in humans, animals, or the environment and may spread from one to the other, as well as from one country to another. However, the scope of One Health as envisioned by international organizations (WHO, FAO, OIE, UNICEF), the World Bank, and numerous national organizations also clearly embraces other disciplines and domains, including environmental and ecosystem health, social sciences, ecology, wildlife, land use, and biodiversity. The declaration of November 3rd as One Health Day is one recent event that could aid in raising global awareness of the One Health concept, notably among students but also more widely. One Health Day is observed by holding educational and awareness-raising activities all across the world. It is especially encouraged for students to develop One Health projects, put them into action, and submit them to an annual competition for the top student-led projects in each of the four global areas. It is unlikely that effective mitigation methods will be developed if today’s health issues are solely approached from a medical, veterinary, or ecological point of view because they are frequently complex, transboundary, multifactorial, and affecting several species. The focus of this year’s World Rabies Day, “Rabies: All for 1, One Health for All” builds on the One Health initiative’s success in 2022 by emphasizing more cooperation, equality, and the improvement of health systems. The phrase is a reference to Alexandre Dumas’s well-known novel.

The Three Musketeers can be compared to a group of people who overcome conflict and unfairness to accomplish their objectives; there is a direct connection between the hardships of those involved in rabies control and our collective efforts to eradicate the illness. To reach our global target of 0 human deaths from dog-mediated rabies by 2030, the international community must overcome inequities in health systems and conflict #ZeroBy30. The occasion presented by this event also provides a chance to remind all parties involved that the fight against rabies must be ongoing in order to reduce the number of rabies-related fatalities. The United Against Rabies Forum, which has the support of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH), and the World Health Organization (WHO), adopts a multi-sectoral, One Health approach by bringing together governments, vaccine manufacturers, researchers, NGOs, and development partners.

The phrase “All for 1” captures the duty that each and every one of us has in the fight to eradicate rabies. Everyone may contribute to saving a life and strive toward achieving One Health. Individuals and animals can receive assistance from communities, and everyone can efficiently collaborate towards a common objective. The number 1 can be used to describe a single person making a difference, a community, our singular objective, how one vaccine protects all animals, and how one PEP course can save a life. The focus of the theme is on major developments in the rabies community, such as cooperation demonstrated by the United Against Rabies Forum and efforts to operationalize One Health – enhancing the health of people, animals, and the environment because the three are interdependent. Additionally, it covers major worldwide developments, including the World Bank’s creation of its Pandemic Prevention Fund and the urgent need to improve health systems as a whole. This can be accomplished by creating the groundwork for more disease/health interventions and increasing capacity through rabies control and elimination activities. One Health is a key idea in the Zero by 30: Global Strategic Plan and is mentioned in light of the following:

1) The eradication of rabies serves as a paradigm for One Health cooperation.

2) The creation of national strategic plans for eradicating rabies.

3) Partners from all industries are involved in international collaboration.

The banner created for this year’s topic combines all essential parts of rabies prevention, underlining the necessity of cooperation and a properly crafted cocktail of strategies: rabies cannot be eradicated by simply immunizing dogs or simply compiling statistics. Education and PEP access alone won’t be enough to end rabies. In addition to all the other crucial elements required to develop a truly One Health rabies elimination strategy, each circumstance requires its own specifically designed approach to public education, dog vaccination, case monitoring, and collaboration with all appropriate agencies.

The term “One Health” refers to a philosophy that acknowledges the interdependence of the health of people, animals, and the environment. In the fight against rabies, it is crucial to comprehend the importance of holistic approaches to disease control. By treating the health of all these elements simultaneously, we effectively combat the disease and maintain the delicate balance of our ecosystems. The One Health strategy uses rabies as an example because it has zoonotic potential, or the ability to spread from animals to people. It is crucial for veterinary and medical specialists to work together to bridge the species gap in disease transmission. The importance of an integrated strategy that takes ecological aspects into account, such as the habitat and behavior of reservoir animals, is further highlighted by the knowledge that environmental factors play a role in rabies transmission.

Human rabies prevention is of utmost importance, and vaccination is the way to do it. It’s crucial to comprehend the ideas behind pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis. Pre-exposure immunization safeguards people who are more likely to be exposed, whereas post-exposure prophylaxis is essential for anyone who has been bitten by a potentially rabid animal. To lower the number of human rabies cases, it is critical to remove obstacles to widespread human vaccination, such as those related to vaccine access and education. Rabies exposure falls into one of three categories, according to World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations for post-exposure care: Category-I is the least serious and occurs when a person touches or feeds infected animals but does not display any skin lesions; category-II is when a person receives minor scratches without bleeding or is licked on broken skin by an infected animal; and category-III is when a person sustains multiple bites, scratches, or licks on broken skin or comes into contact with infected mucus. No matter how the victim came into contact with the bats, exposure to them falls under category-III, and they are handled as such. While anti-rabies Immunoglobin-A liquid or freeze-dried preparation containing rabies antibodies isolated from plasma, should be given for category-III or to those with impaired immune systems, anti-rabies vaccination is advised for category-II and III. To create a more effective control program, it is therefore necessary to take a comprehensive, strategic, and focused approach to control and prevent with input from the local, national, and international fields of human, animal, and environmental health. The execution of vaccination programs and home and community dog and cat population reduction are the main ways that various government and non-government organizations are involved in rabies control and prevention activities. In addition, awareness initiatives and post exposure prophylaxis (PEP) have been utilized to combat dog bite incidents. The number of rabies cases has not dropped as a result of these programs, though, because there aren’t any multi-sectoral management measures in place. The “One Health Approach” is the most effective strategy for lowering rabies in this situation since it draws on the successful lessons and strategies from other countries. As part of the government’s continued efforts to increase public knowledge of the disease, the National Centre for Disease Control (NCDC), formerly the National Institute of Communicable Disease, has started a trial study to decrease human rabies mortality. Health professionals participating in the research will receive training in handling animal bites, and notices urging people to seek post-exposure therapy will be placed on buses and in other public places. In addition to enhancing hospitals’ capacity to identify illnesses, the pilot initiative, carried out in partnership with WHO, aims to ensure that anti-rabies vaccines and serum are always available. The pilot heavily relies on collaboration with partners in other sectors as well as the national agency for animal husbandry. The Association for Prevention and Control of Rabies in India, the Rabies in Asia Foundation, and the Animal Welfare Board of India—all of which are actively promoting the Animal Birth Control, Anti-Rabies Program in major metropolitan areas—have all made notable contributions to the improvement of the situation.

The relationship between our shared environment, animals’ health, and human health is acknowledged in “One Health” programs. Controlling rabies outbreaks in both humans and animals is the main goal of a One Health approach. The need for post-exposure immunizations and the cost of managing rabies in humans are reduced when rabies is prevented from spreading from animals to humans. It is also widely acknowledged that a One Health approach is an affordable means of reducing rabies cases in low-income developing countries. It could be wise to perform a pilot study with both urban and rural groups from different locations before rolling out the program on a larger scale in order to evaluate the metrics for success of this approach. If the PEP rabies vaccine were made more widely available, more people would have access to it and be able to purchase it. If there were rabies diagnostic centers in each regional laboratory, the workload at the Central Reference Laboratory would reduce. Competent medical professionals working at the nearby laboratories would ensure the program’s quality and effectiveness. The cooperation and communication of medical specialists is another important element in the overall efficiency of the rabies control and prevention program. Active disease surveillance might be helpful for diagnosing the condition. Therefore, cooperation between each of these sectors—the human, animal, and environmental sectors—as well as an integrated approach are both essential for carrying out a successful strategy. It is essential to control the dog population and concentrate on mass vaccinating animals, however the latter should follow guidelines for animal welfare. Government regulations must categorically prohibit the killing and torturing of animals, and if euthanasia is the only other option, then it should be used in place of the horrifying slaughter of animals. Pet ownership and public safety records can also be made available with a legislative requirement for mandatory registration. Castration and spaying are two examples of animal birth control procedures that can be used to reduce the number of communal or street dogs. Prior to taking these activities, a reliable data collection and reporting system is required. A One Health plan is best served by a routine reporting system that allows for periodic progress reviews, an understanding of the state of endemic and sporadic illnesses, and their socioeconomic impact. The creation of national policies or control programs will gain from this information. Given that the symptoms of rabies are ambiguous or widespread among illnesses of the nervous system, it is not surprising that cases of rabies can go unreported and escalate into a more serious problem when registration facilities at tertiary care clinics and hospitals are unable to access clinical care and diagnostic confirmation databases. In order to create control roadmaps, it would be helpful to have a system that provides exact data on the number of dogs, suspected or confirmed rabies cases, and the total population afflicted with rabies at a particular area and time. The assessment of human-dog population densities, data analysis, meticulous management, and vaccination statistics are other factors that affect how effectively rabies control programs work. A common issue in projects requiring multi-sectoral coordination is a lack of coordination and information sharing among the stakeholders involved. It will be simpler to identify problem areas and create management plans with the help of primary data collecting, reporting, and storage in national and international databases. In most countries, rabies is not a common disease. As a result, in these countries, the sole official monitoring techniques are employed to acquire rabies data. Rabies surveillance may become increasingly difficult as a result of operational issues with sample submission to labs and non-compliance with direct data reporting to line ministries. As a result, there will be a greater likelihood that inaccurate and incomplete data may be generated.

The majority of the animal health sector’s focus is on commercially significant livestock diseases. That list does not include rabies. It would be easier to gather accurate information for strategic mass vaccination and population control by including rabies among the diseases that the Animal Health Sector monitors. To protect the immunological status of the sensitive animal population and to prevent transmission, a functioning surveillance system that produces primary data is essential. As humans, domestic animals, and wildlife territories are close together, controlling rabies in wildlife and at the wildlife-domestic animal interface may be essential. In order to effectively prevent the spread of rabies from wildlife to domestic animals and people, rabies monitoring and control efforts must be expanded to include wildlife. Large-scale oral vaccination campaigns with at least 70% coverage, taking into account the ecological and epidemiological characteristics of rabies and wildlife species, could be one way to control the spread of the disease in wildlife. These campaigns have been successful in foxes in Europe, raccoons in Canada, and coyotes in the United States. Bait carrying the oral rabies vaccination (ORV) can be placed in natural habitats such as buffer zones, national parks, wildlife reserves, community woods, and suburban areas. It might be beneficial to lessen the possibility of rabies spreading from wildlife to cattle to people and vice versa.

Following a dog bite, PEP is the only method for human rabies prevention. Naturally, the burden of rabies will increase if PEP is not available right after following a bite from a suspected rabid animal. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and PEP are both accessible at government and private hospitals in urban areas. PrEP and PEP, however, are not widely accessible in rural locations for a variety of reasons. As of now, the majority of hospitals are located in urban areas, making it challenging for those living in rural areas to get medical attention when bitten. By 2030, there must be no human rabies deaths, hence it is essential to ensure adequate PEP supply. Another way to increase the number of lives saved in the near future is to use an integrated dog bite case management (IBCM) strategy, which incorporates rabies surveillance and collaboration between veterinary and public health professionals to evaluate the risk of rabies among animal bite patients and biting animals. With significant collaborative local, national, and international actions, rabies can be permanently controlled.

Mass dog vaccination campaigns are a low-cost way to avoid rabies. By immunizing 70% or more of the dog population, the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) and World Health Organization (WHO) assert that the incidence of rabies can be greatly decreased. As a result, exposure to humans will be immediately decreased. In instance, mass canine vaccination campaigns are an investment that will pay off and be more cost-effective over time. Thus, broad dog vaccination is one of the key tactics we advocate for use in lowering rabies in both the human and animal populations. For this plan to be as effective as possible, both domesticated dogs and strays must be properly registered, kept in enclosures, and compelled to receive vaccinations. It’s also advisable to give dogs booster shots afterward because skipping them puts their immunity at danger. In this case, it is still possible for rabies infections to occur after vaccination. Vaccination is one of the most important ways to avoid rabies. Lack of immunity could be the result of poor vaccine administration. The most common reasons why vaccinations don’t work include inappropriate handling, storage, and transportation, along with production problems. Therefore, both vaccination quality and effectiveness are essential for rabies control programs to be successful.

In-depth public education efforts directed at at-risk populations would be necessary in the event of any disease outbreak, including rabies. Communities in India are not entirely aware of rabies. Numerous elements, including socioeconomic issues and rabies’ failure to be designated as a priority disease, might be held responsible for this. However, information on dog vaccination, PEP accessibility, and anti-dog bite measures could help to ameliorate the situation. The capability for diagnosis can be increased by well-equipped laboratories. For the management of human rabies, it is essential to put prophylactic measures into place as well as a conceptual framework. In this regard, using nearby diagnostic services may aid in evaluating and providing targeted immunization coverage. Large cities have a number of well-equipped laboratories that meet OIE standards, but more has to be done to improve accessibility. Even though using quick test kits for initial screening could alleviate the load on these labs, there are no other options if the required laboratory facilities are not accessible. When fewer clinical symptoms are employed to diagnose an illness, poor accuracy is predicted, and cheap service prices are essential for enhanced detection and reporting as well as the availability of trustworthy diagnoses. To determine associated risk factors, the predominant mechanism of transmission, socioeconomic repercussions, and locally specific disease dynamics, epidemiology field study on rabies may be useful. Therefore, carrying out this research could be an excellent place to start when developing integrated multi-sectoral rabies management plans. (1) The creation of instruments to gauge the scope of rabies infections is one of the main areas of research interventions and advances. (2) The availability of quick and affordable diagnostic tests. (3) Research promoting “soft” population control methods like reducing the number of dogs, encouraging responsible dog ownership, and managing rabies’ effects on the environment. (4) Data collection on relevant animal species’ basic population factors, such as dog populations’ size, turnover, accessibility, and ownership status, should be done periodically in a variety of contexts. (5) Public education initiatives to increase awareness about PEP, first aid, and how to handle animal bites. (6) Using the active mobilization of NGOs, community-based organizations, animal welfare societies, the media, leaders, and other powerful groups, raising awareness of the disease and responsible dog ownership.

The participation of the general population is crucial to the program’s success. Increased involvement may be aided by a variety of awareness initiatives. Additionally, the accessibility of essential facilities like roads, power, hospitals, and veterinary clinics will determine how a program is conducted. The amount of education and income a person has may have an impact on their willingness to participate in mass vaccination efforts, post-exposure vaccination campaigns, and animal birth control programs. Socioeconomic, environmental, animal, and human aspects are among the crucial—though not exclusive—factors to take into account. In order to make meaningful progress in rabies control and prevention, a “Multi-sectoral One Health Approach” may be a good method. In some nearby nations, like Bhutan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka, a One Health strategy has been effective. The country of India, in particular, just finished a trial of this management strategy in five different cities across the country and has concluded that taking into account both the human and animal components is crucial in this strategy. Its success could depend on a strong political commitment and strict governmental action. It is not sufficient to concentrate only on human immunization to eradicate rabies. Targeting animal reservoirs with widespread immunization campaigns is similarly important. When properly carried out, these programs can break the transmission chain, safeguarding both people and animals. For effective rabies management, vaccination strategies must be tailored to varied animal populations, including both domestic pets and wild animals. Raising public knowledge of rabies prevention is crucial, and effective communication techniques are essential. To promote responsible pet ownership, secure encounters with wildlife, and prompt medical attention following potential exposure, it is crucial to dispel rabies myths and misconceptions. Programs for capacity-building and training are essential for enabling individuals working on the front lines of rabies control. The unsung heroes in this conflict are veterinarians, medical personnel, and municipal authorities. To properly diagnose, treat, and prevent rabies, they need the information and tools. Local leadership is very important in grass-roots initiatives to lower the incidence of rabies. Initiatives to control rabies at the national and worldwide levels, governed by laws and other regulations, offer the required foundation for coordinated efforts. The promotion of rabies prevention within international health agendas guarantees that this crucial issue receives the consideration and funding it requires. International cooperation is necessary to fight rabies because it knows no borders. Developing new tools and techniques requires knowledge exchange and team research. A coordinated effort from governments, organizations, and individuals is required to mobilize resources for a global eradication effort to eradicate rabies.

It might be beneficial to share experiences and implement professional containment techniques, such as the isolation and quarantine procedures that are common in veterinary medicine. The latter are situations where, unlike in human medicine, veterinary practices are extensively and strictly applied since they stand for the fundamental rules for limiting the entry and spread of diseases in uninformed animal populations. Given that ecological changes, molecular differences in infectious agents, and interactions between wild animals and people represent the primary drivers for the creation of new infections, veterinarians are particularly crucial in wildlife surveillance, which becomes a crucial component in the control of rabies. Therefore, cooperation between veterinary communities involved in wildlife monitoring and human medical communities is essential in the development of preventive strategies. This collaboration must go in two directions to provide early and precise information, which is lacking in the majority of developing countries. By utilizing georeferencing software to link environmental factors like temperature, humidity, soil type, vector density, pathogen, host, exposure, and transit of animals and people, veterinary epidemiology enables alignment with disease forecasting and modeling research. The emergence of a sophisticated Geographic Information System under a comprehensive viewpoint for the development of research related to the control of the disease would be made possible by the convergence of factors, including the accessibility of these geocoded multi-temporal data and multi-professional collaborations globally.

The fight against rabies is a crucial one in the effort to achieve “One Health, Zero Death.” We can picture a world in which rabies is a thing of the past by taking a complete approach that includes immunization, instruction, and international collaboration. By putting the health and well-being of all species first, we make a big step toward a more secure and peaceful international community. By working together, we can ensure that “One Health, Zero Death” becomes a reality by 2030, where the threat of rabies is no longer a concern for our planet. In disease prevention initiatives, the idea of one health is becoming more and more prevalent. The wellbeing of people, animals, and the environment is interdependent and intrinsically intertwined, as recent instances like COVID-19 and antimicrobial resistance have demonstrated to the globe. The establishment of the WHO NTD roadmap and the One Health companion document, both of which directly address rabies, as well as talks and mentions of One Health in the G20 summit (2023), among other significant platforms, all demonstrate the significance of the concept. Elimination of rabies is a prime example of the One Health strategy, involving participation and cooperation from the human, animal, and environmental sectors. It is also frequently used as an illustration of operationalizing One Health. Whether you are a professional or a member of the public interested in rabies, this One Health portion of the theme has been created to be inclusive, ensuring that everyone views themselves as a vital partner who can make a difference and help us as a group to accomplish rabies elimination. In keeping with the “Zero by 30: Global Strategic Plan for the elimination of dog-mediated human rabies deaths by 2030,” this topic promotes cooperation, teamwork, and a coordinated approach to rabies elimination, or “Zero Deaths.” In the second section of the theme, “Zero deaths” are mentioned. This emphasizes that rabies is preventable and that it can be completely eradicated, which is completely in line with the Zero by 30 Global Strategic Plan. In actuality, the only NTD that can be prevented by a vaccine is rabies. This aspect of the subject also serves as a reminder that, although having achieved tremendous progress, we still have a clear objective to work toward and must continue to cooperate in order to do so.