“One world, one health: Prevent zoonoses!”

Dr. Srashti Dixit1*, Dr. Manisha Tyagi2

1Ph.D. Scholar, Department of Livestock Production and Management, DUVASU, Mathura

2M.V.Sc. Scholar, Department of Livestock Production and Management, DUVASU, Mathura

*Corresponding author- srashtidixit5@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Zoonoses are infectious diseases that are transmitted from animals to humans and/or from humans to animals. The whole concept of “One World, One Health,” is based on the fact that humans, animals, and the environment are interconnected to each other, implying that the world has recognized the interrelationship between ecology, animal diseases, and public health, with the aim of restoring and maintaining amity and kinship. Although the name “One Health” is relatively new, the notion has long been recognized on a national and international scale. One health is a collaborative, multisectoral, and transdisciplinary strategy aimed at obtaining optimal health outcomes by recognizing the connectivity between humans, animals, plants, and their common environment at the local, regional, national, and global levels. The purpose of this article is to disseminate collated information and raise awareness.

Keywords: Zoonoses, One health, WHO, Animals

- INTRODUCTION

Zoonoses are infectious diseases that are transmitted from animals to humans and/or from humans to animals . Approximately 75% of new emerging and re-emerging disease pathogens are zoonotic, with 60% spreading from domestic and wild animals and 80% posing a bioterrorism risk. Several zoonotic disease outbreaks have occurred over the last 20 years. Some zoonoses, such as Ebola virus disease, salmonellosis, Marburg illness, rabies, and anthrax, can create repeated epidemics. Others, like the new coronavirus that causes COVID-19, have the potential to produce global pandemics. The numerous linkages between animals, humans, and ecosystems have increased the possibility of disease spillover and burden. As a result, this complex health concern necessitates a multi-sectoral partnership known as the One Health strategy .

The “One World, One Health” notion first appeared at a Wildlife Conservation Society seminar in New York in 2004. The conference focused on disease movements among human, domestic animal, and wildlife populations, as well as identifying goals for an international, interdisciplinary strategy to combating risks to animal, human, and eco-system health . The geographical component, the ecological component, human activities, and food-agricultural components may all be highlighted as significant factors within the ‘One World – One Health’ strategy .

One Health is an approach that recognizes that human health is inevitably linked to animal health and the health of our shared environment. One Health is not a new concept, but it has gained prominence in recent years. This is because a variety of variables has altered relationships between humans, animals, plants, and the environment.

Human populations are exploding and spreading into new locations. As a result, more people are living in close proximity to wild and domestic animals, including cattle and pets. Animals are required in human life for a variety of reasons, like food, livelihood, travel, sport, education, and companionship. Close interaction with animals increases the likelihood of disease transmission between humans and animals.

Climate changes, such as deforestation and intensive farming practices, have occurred across the planet. Variation in climatic conditions and habitats can open up new avenues for disease transmission to animals.

International trading and travelling have boosted the mobility of people, animals, and their products. As a result of which pathogen can quickly spread across borders and around the world.

These changes have resulted in the spread of current or known (endemic) zoonotic illnesses, as well as new or emerging zoonotic diseases, which are diseases that can transfer between animals and humans.

- Rabies

- Anthrax

- Brucellosis

- Salmonella infection

- West Nile virus infection

- Q Fever (Coxiella burnetii)

- Lyme disease

- Ringworm

- Ebola

- CAUSES RESPONSIBLE FOR ZOONOSES

People are benefitted greatly from animals. Many individuals interact with animals, on regular basis

It has been recognized that animals (whether domestic or wild) are the source of 60% of known human infectious diseases, as are 75% of new human diseases and 80% of pathogens that could possibly be utilized in bioterrorism. We also know that human populations require a regular protein diet of milk, eggs, or meat, and that protein insufficiency can be a public health issue .

The unprecedented flow of commodities and people allows pathogens of all kinds to spread and multiply around the world, and climate change can allow them to expand their range, particularly through vectors such as insects colonizing new areas that were previously too cold for them to survive the winter.

The sickness reduces global food animal production by more than 20%, implying that even animal diseases that are not transmissible to humans can cause severe public health problems due to shortages and deficiencies.

Because of the intimate relationship between humans and animals, it is critical to be aware of the frequent ways in which people can become infected with microorganisms that cause zoonotic diseases by following ways :

Direct contact: Coming into contact with an infected animal’s saliva, blood, urine, mucus, faeces, or other body fluids. Touching animals as well as bites or scratches also.

Indirect contact: Coming into contact with areas where animals live and roam, or objects or surfaces that have been contaminated with germs. Examples include aquarium tank water, pet habitats, chicken coops, barns, plants, and soil, as well as pet food and water dishes.

Vector borne: Being bitten by arthropods like tick or an insect like a mosquito or a flea.

Food borne: Consuming dangerous foods or beverages, such as unpasteurized milk, undercooked meat or eggs, or raw fruits and vegetables contaminated with faeces from an infected animal.

Water borne: Drinking or coming into touch with water tainted with an infected animal’s faeces.

- HOW DOES A ONE-HEALTH STRATEGY WORK?

The One Health strategy combines professionals from human, animal, and environmental health, as well as other disciplines and sectors, in monitoring and regulating public health concerns and learning about how diseases travel among humans, animals, plants, and the environment .

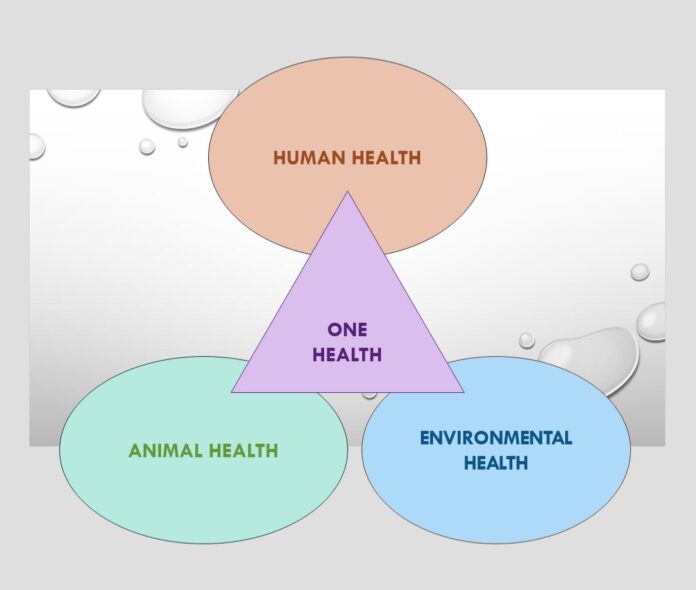

Figure: 1 How does a One Health strategy work?

Human, animal, and environmental health specialist must collaborate for successful public health interventions. Human health professionals like doctors, nurses, public health practitioners, epidemiologists, animal health professionals like veterinarians, paraprofessionals, agricultural workers) and environment professionals like ecologists, wildlife experts and others must communicate, collaborate, and coordinate the activities. Law enforcement, legislators, farmers, communities, and even animal owners might all be important stakeholders in a one health strategy. There is no single person, organization, or sector that can handle concerns at the animal-human-environment interface .

The One Health concept has the potential to:

- Prevent zoonotic disease epidemics in both animals and humans.

- Increase the safety and security of food.

- Reduce antimicrobial resistance while improving human and animal health.

- Maintain global health security.

- Conservation of biodiversity and the environment.

A One Health approach can produce the highest health results for people, animals, and plants in a shared environment by encouraging collaboration across all sectors.

- MANHATTAN PRINCIPLES FOR PREVENTION OF ZOONOSES

“Manhattan Principles” are recommended by the organizers of the “One World, One Health” event, includes 12 recommendations for establishing a more holistic approach to epidemic / epizootic disease prevention and ecosystem integrity for the benefit of humans, their domesticated animals, and the foundational biodiversity .

- Recognize the captious relationship between human, animals, and wildlife health, as well as the threat disease poses to people, their food supply and economy, as well as the biodiversity required for maintaining the healthy settings and functional ecosystems that we all rely on.

- Recognize that decisions about land and water usage have actual health consequences. When we fail to recognize this link, we see changes in ecosystem resilience and shifts in disease emergence and dissemination patterns.

- Integrate animal health science into global disease prevention, surveillance, monitoring, control, and mitigation.

- Recognize the importance of human health programmes in conservation efforts.

- Create adaptive, holistic, and forward-thinking approaches to the prevention, surveillance, monitoring, control, and mitigation of emerging and resurging illnesses that fully account for the complex interactions between species.

- When developing solutions to infectious disease problems, look for ways to completely combine biodiversity conservation viewpoints and human requirements (particularly those related to domestic animal health).

- Reduce demand for and improve regulation of the worldwide live wildlife and bushmeat trade, not just to safeguard wildlife populations, but also to reduce the hazards of disease mobility, cross-species transmission, and the formation of novel pathogen-host associations. The costs of this global trade in terms of public health, agriculture, and conservation are immense, and the international community must handle this trade as the serious menace that it is.

- Limit mass killing of free-roaming animal species for disease control to circumstances where a multidisciplinary, international scientific consensus exists that a wildlife population offers an immediate, serious threat to human health, food security, or wildlife health in general.

- Increase global human and animal health infrastructure investment in proportion to the seriousness of new and resurging disease threats to people, domestic animals, and wildlife. Improved capacity for global human and animal health surveillance, as well as clear, timely information sharing (that takes language barriers into account), can only help improve response coordination among governmental and nongovernmental organizations, public and animal health institutions, vaccine / pharmaceutical manufacturers, and other stakeholders.

- Establish collaborative partnerships among governments, local residents, and commercial and public sectors.

- Provide sufficient resources and support for global wildlife health surveillance networks that exchange disease information with the public health and agricultural animal health communities as part of early warning systems for disease development and resurgence.

- Invest in educating and raising awareness among the world’s people, as well as in influencing policy, to promote realisation that we need to better understand the linkages between health and ecological integrity in order to improve prospects for a healthier planet.

CONTROL OF ZOONOSES WITH ONE HEALTH CONCEPT

The only way to avoid all of these new risks is to harmonies and integrate current health governance systems at the global, regional, and national levels .

The OIE has modernised its worldwide information system on animal diseases (including zoonoses) with the creation of WAHIS, a mechanism in which all countries are linked online to a central server that collects all mandatory notifications sent to the OIE, covering 100 priority terrestrial and aquatic animal diseases.

The World Health Organization has enacted the International Health Regulations, which impose new requirements on its members. GLEWS, the Global Early Warning System, is a platform shared by the OIE, WHO, and FAO to improve early warning on animal diseases and zoonoses worldwide.

The OIE, WHO, and FAO (along with UNICEF, the UN System Influenza Coordinator [UNSIC], and the World Bank) have prepared a consensus document on global measures needed to better coordinate medical and veterinary health policies, taking into account new requirements for zoonoses prevention and control. At a conference in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, in October 2008, Ministers from over 100 nations presented and adopted this statement.

At the national level, the OIE has established a mechanism through which countries can volunteer to have an OIE independent evaluation of their animal health system, including the compliance of their Veterinary Services with international quality standards adopted and published by the OIE and serving as the foundation for good governance. More than 120 nations have already taken this step as part of the OIE PVS (Performance of Veterinary Services) tool’s global implementation.

A PVS evaluation gives a preliminary diagnosis of governance, which can then be followed by assistance in the form of a gap analysis mission to determine what “treatment” will be required, based on the country’s own goals, to address shortcomings identified during the diagnosis.

- CONCLUSION

The present debates on the concept of “One World, One Health” would eventually lead to all countries committing to making their animal health condition open and establishing procedures for early identification of disease outbreaks. This would necessitate a solid legal foundation and national investments to enable nations to attain compliance with quality standards, particularly in Veterinary Services, with the cooperation of the OIE, their government, and, where appropriate, interested foreign donor agencies. The Member Countries and Territories will continue to demonstrate their commitment to further strengthening the WHO and OIE’s international legal framework in order to comply with all of the rules that prevent other Members from being put at risk because diseases were not detected and reported promptly. Nonetheless, the concept of “One World, One Health” should not be used as a cover for risky efforts such as attempting to attain economies of scale based on purely theoretical conceptions worthy of a sorcerer’s apprentice, such as merging the Veterinary and Public Health Services.

REFERENCES

- World Health Organization. Zoonoses. 2022 cited 2023 Jul 26 https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/zoonoses

- Zoonotic Diseases. 2021 cited 2023 Jul 11 https://www.cdc.gov/onehealth/basics/zoonotic-diseases

- World organization for animal health. 2009 2023 Jul 11

https://www.woah.org/en/one-world-one-health

- The-Manhattan-Principles. https://oneworldonehealth.wcs.org/About-Us/Mission/.aspx

- Berthe FCJ, Bouley T, Karesh WB, Le Gall FG, Machalaba CC, Plante CA. (2018).Operational framework for strengthening human, animal and environmental public health systems at their interface. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group.

- Calistri, P., Iannetti, S., L. Danzetta, M., Narcisi, V., Cito, F., Di Sabatino, D., Bruno, R., Sauro, F., Atzeni, M., Carvelli, A., & Giovannini, A. (2013). The components of ‘one world—One health’ approach. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases, 60, 4–13.