PET BORNE ZOONOTIC INFECTION & ITS PREVENTION

By Dr Amit Bharadwaj

Specialist in animal surgical intervention,Pune.

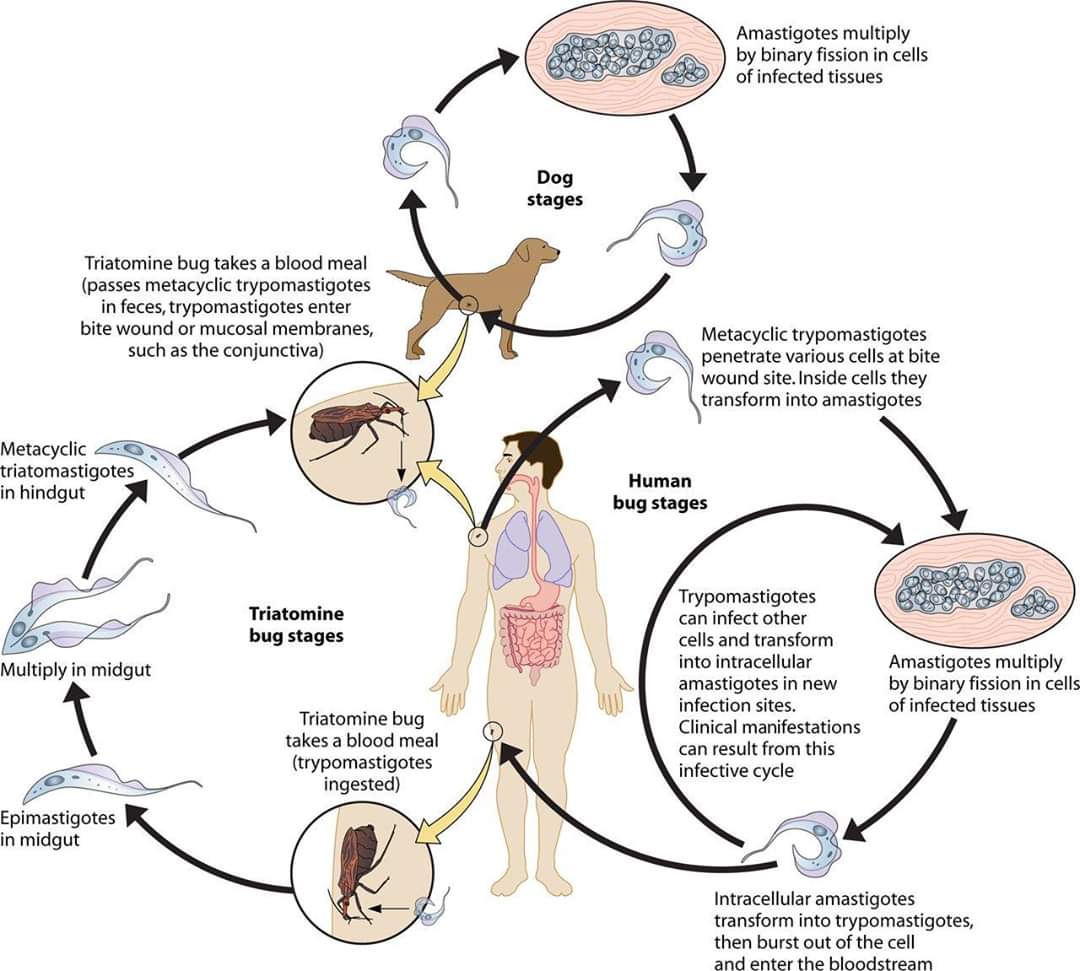

Zoonoses are diseases that can be transmitted from animals to humans. They can be acquired via insect vectors, food, and direct or indirect contact with animals. More than 250 zoonoses have been described, and they are caused by a wide variety of pathogens, including viruses, rickettsia, bacteria, fungi, and parasites. Some of the diseases are rare, such as rabies and plague; others, such as cat-scratch disease, are common. The transmission of zoonotic diseases is both diverse and dynamic. Although illnesses such as salmonellosis and campylobacteriosis are by far the most common zoonotic infections in humans and are transmitted most often by food, there is a small risk of acquiring illness from pets and wildlife.

Because many pet- and wildlife-related zoonoses are acquired via fecal-oral or direct contact routes, the inquisitive nature of children puts them at a higher risk for infection than adolescents and adults.

Pet ownership has many psychological and social benefits and should not be discouraged, with the exception of households that contain immunocompromised individuals or children younger than age 5 years, which should not have reptiles because of the risk of salmonellosis.

Pets serve valuable social roles in society . Pets may lower blood pressure, reduce cholesterol and triglyceride levels, and improve feelings of loneliness, while increasing opportunities for exercise, outdoor activities, and socialization .Despite these benefits, pets present zoonotic risks, especially for immunocompromised hosts.

In the practice environment veterinary personnel are frequently exposed to the

infectious pathogens, many of which are zoonotic. Education on the prevention of zoonotic

diseases is a considerable part of the clinical practice of veterinarians. The ‘One Health, One World’ paradigm for global health recognizes that most new human infectious diseases will emerge from animal reservoirs. With the cats and dogs closely sharing domestic environment with humans, they have the potential to act as sources and sentinels of a wide spectrum of zoonotic diseases. Among the emerging human infections, nearly 75% of the diseases are likely to emerge from an animal reservoir. This fact reaffirms the significance of zoonotic disease prevention and control (Taylor et al., 2001). The factors contributing to the emerging infections include globalization of the economy; increased world tourisml; ecological changes such as agricultural shifts, migration, urbanization, deforestation, or dam construction; and increased contact with animals due to development and travel. These factors place more people at risk for these diseases as well as increase the spread and emergence of infectious diseases.

From a ‘One Health’ perspective, companion animals can serve as sources of zoonotic

infections, as intermediate hosts between wildlife reservoirs and humans, or as sentinel or proxy species for emerging disease surveillance. The role of companion animals in the human domestic and peridomestic environment, the major companion animal zoonoses and the potential for emergence of new human infections transmitted from these species are discussed here.

Household pets as a source of zoonotic infections ———-

Pets, particularly dogs and cats, play important roles in societies throughout the world. Many Indian households own a dog or cat commonly. Other pets include birds, monkeys, reptiles, and rodents. Pets are important companions in many of the households where they live and are often considered family members. Pets contribute to the physical, social, and emotional development of children and to the well-being of their owners, particularly elderly people.

Although pets offer significant benefits to society, there are well-known health risks associated with owning a pet. While animal bites and allergies to pets are the most common health risks, over one hundred infectious agents can be transmitted either directly or indirectly to humans, some of which are listed in table 1. The most common modes of transmission include direct skin contact (e.g. fungal diseases and sarcoptic mange); bite and scratch wounds (e.g. Pasteurellosis and rabies); fecal-oral transmission (e.g. roundworms and toxoplasmosis), especially in infants and young children; and vector transmission. Veterinary standard precautions

A. Personal Protective Actions and Equipment ————

1. Hand hygiene

Hand-washing is the single most important measure to reduce the risk of disease

transmission. Hands should be washed between animal contacts and after contact with blood, body fluids, secretions, excretions, and equipment or articles contaminated by them. Hand-washing with plain soap and running water mechanically removes soil and reduces the number of transient organisms on the skin, whereas antimicrobial soap kills or inhibits growth of both transient and resident flora. All soaps also have the effect of dissolving the lipid envelope of enveloped viruses, and have cell wall effects that are bactericidal.

Alcohol-based gels are highly effective against bacteria and enveloped viruses and may be used if hands are not visibly soiled. Alcohol-based gels are not effective against some non-enveloped viruses (e.g., norovirus, rotavirus, parvovirus), bacterial spores (e.g., anthrax, Clostridium difficile), or protozoal parasites (e.g., cryptosporidia). Antimicrobial-impregnated wipes (i.e., towelettes), followed by alcohol-based gels, may be used when running water is not available. Used alone, wipes are not as effective as alcohol-based hand gels or washing hands with soap and running water.

2. Use of gloves and sleeves

Gloves reduce the risk of pathogen transmission by providing barrier protection. They

should be worn when touching blood, body fluids, secretions, excretions, mucous membranes, and non-intact skin. However, wearing gloves (including sleeves) does not replace hand-washing. Gloves should be changed between examinations of individual animals or animal groups (e.g., litter of puppies/kittens, group of cattle) and between dirty and clean procedures on a single patient. Gloves come in a variety of materials. Choice of gloves depends on their intended use. If latex allergies are a concern, acceptable alternatives include nitrile or vinyl gloves.

3. Facial protection

Facial protection prevents exposure of mucous membranes of the eyes, nose and mouth to infectious materials. Facial protection should be used whenever exposures to splashes or sprays are likely to occur. Facial protection should include a mask worn with either goggles or a face shield. A surgical mask provides adequate protection during most veterinary procedures that generate potentially infectious aerosols. These include dentistry, nebulization, suctioning, bronchoscopy, lavage, flushing wounds and cleaning with high pressure sprayers.

4. Respiratory protection

Respiratory protection is designed to protect the respiratory tract from zoonotic infectious diseases transmitted through the air. The need for this type of protection is limited in veterinary medicine. However, it may be necessary in certain situations, such as when investigating abortion storms in small ruminants (Q fever), significant poultry mortality (avian influenza), ill psittacine birds (avian chlamydiosis) or other circumstances where there is concern about aerosol transmission. The N-95 rated disposable particulate respirator is a mask that is inexpensive, readily available, and easy to use.

5. Protective outerwear

Use of outerwear like lab coats, coveralls, gowns, footwear and head-covers provide a barrier between persons and infectious agents. Although use of these alone may not be the ultimate solution to prevent diseases, adjoining environment protection measures are also helpful in preventing zoonotic infections.

6. Bite and other animal-related injury prevention

According to a study the majority (61%-68%) of veterinarians suffer an animal-related

injury resulting in hospitalization and/or significant lost work time during their careers. These are mainly dog and cat bites, kicks, cat scratches and crush injuries, and account for most occupational injuries among veterinarians. Veterinary personnel reliably interpret the behaviors associated with an animal’s propensity to bite; their professional judgment should be relied upon to guide bite prevention practices. Approximately 3 to 18% of dog bites and 28 to 80% of cat bites become infected. Most clinically infected dog and cat bite wounds are mixed infections of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria.

Veterinary personnel should take all necessary precautions to prevent animal-related

injuries in the clinic and in the field. These may include physical restraints, bite-resistant gloves, muzzles, sedation, or anesthesia, and relying on experienced veterinary personnel rather than owners to restrain animals. Practitioners should remain alert for changes in their patients’ behavior. Veterinary personnel attending large animals should have an escape route in mind at all times. When bites and scratches occur, immediate and thorough washing of the wound with soap and water is critical. Prompt medical attention should be sought for puncture wounds and other serious injuries. The need for tetanus immunization, antibiotics or rabies post-exposure prophylaxis should be evaluated.

B. Protective actions during veterinary procedures

1. Intake of animals

Waiting rooms should be safe environment for clients, animals and employees.

Aggressive or potentially infectious animals should be placed directly into an exam room.

Animals with respiratory or gastrointestinal signs, or a history of exposure to a known infectious disease should be asked to enter through an alternative entrance to avoid traversing the reception area.

2. Examination of animals

All veterinary personnel must wash their hands between examinations of individual animals or animal groups (e.g., litter of puppies/kittens, herd of cattle). Hand hygiene is the most important measure to prevent transmission of zoonotic diseases while examining animals. Potentially infectious animals should be examined in a dedicated exam room and should remain there until initial diagnostic procedures and treatments have been performed.

3. Injections, venipuncture, and aspirations

a. Needlestick injury prevention

Needlestick injuries are among the most prevalent accidents in the veterinary workplace.

The most common needlestick injury is inadvertent injection of a vaccine. In a survey of 701 veterinarians, 27% of respondents had accidentally self-inoculated rabies vaccine and 7% live Brucella vaccine.

The most important precaution is to avoid recapping needles. Recapping causes more

injuries than it prevents. When it is absolutely necessary to recap needles as part of a medical procedure or protocol, a mechanical device such as forceps can be used to replace the cap on the needle.

Following most other veterinary procedures, the needle and syringe may be separated for disposal of the needle in the sharps container. This can be most safely accomplished by using the needle removal device on the sharps container, which allows the needle to drop directly into the container. Needles should never be removed from the syringe by hand. In addition, needle caps should not be removed by mouth. Sharps containers are safe and economical, and should be located in every area where animal care occurs.

b. Barrier Protection

Gloves should be worn during venipuncture on animals suspected of having an infectious disease and when performing soft tissue aspirations.

4. Dental procedures

Dental procedures create infectious aerosols and there is risk of exposure to splashes or sprays of saliva, blood, and infectious particles. There is also the potential for cuts and abrasions from dental equipment or teeth. It has been observed that irrigating the oral cavity with a 0.12% chlorohexidine solution significantly decreases bacterial aerosolization.

5. Resuscitations

Resuscitations are particularly hazardous because they may occur without warning and unrecognized/undiagnosed zoonotic infectious agents may be involved. For example, a dog that presents in respiratory failure after being hit by a car may have been in the road due to clinical rabies. Barrier precautions such as gloves, mask, and face shield or goggles should be worn at all times. Never blow into the nose/mouth of an animal or into an endotracheal tube to resuscitate an animal; instead, intubate the animal and use an anesthesia machine/respirator.

6. Obstetrics

Common zoonotic agents, including Brucella spp., Coxiella burnetii, and Listeria monocytogenes may be found in high concentrations in the birthing fluids of aborting or parturient animals, stillborn fetuses, and neonates. Gloves, sleeves, mask or respirator, face shield or goggles, and impermeable protective outerwear should be employed as needed to prevent exposures to potentially infectious materials. During resuscitation, do not blow into the nose or mouth of a non-respiring neonate.

7. Necropsy

Necropsy is a high risk procedure due to contact with infectious body fluids, aerosols, and contaminated sharps. Non-essential persons should not be present. Veterinary personnel involved in or present at necropsies should wear gloves, masks, face shields or goggles and impermeable protective outerwear as needed. In addition, cut-proof gloves should be used to prevent sharps injuries. Respiratory protection (including environmental controls and respirators) should be employed when band saws or other power equipment are used.

8. Diagnostic specimen handling

Feces, urine, aspirates, and swabs should be presumed to be infectious. Protective outerwear and disposable gloves should be worn when handling these specimens. Discard gloves and wash hands before touching clean items (e.g., microscopes, telephones, food). Although in veterinary practices animal blood specimens have not been a significant source of occupational infection, percutaneous and mucosal exposure to blood and blood products should be avoided. Eating and drinking must not be allowed in the laboratory.

C. Environmental infection control

1. Isolation of infectious animals

Patients with a contagious or zoonotic disease should be clearly identified so their infection status is obvious to everyone, including visitors allowed access to clinical areas. Prominent signage should indicate that the animal may be infectious and should outline any additional precautions that should be taken. Ideally, veterinary practices should utilize a singlepurpose isolation room for caring for and housing contagious patients. Access to the isolation room should be limited and a sign-in sheet should be kept of all people having contact with a patient in isolation. A disinfectant should be use in the footbath just inside the door of the isolation area and used before departing the room.

2. Cleaning and disinfection of equipment and environmental surfaces

Proper cleaning of environmental surfaces, including work areas and equipment,

prevents transmission of zoonotic pathogens. Environmental surfaces and equipment should be cleaned between uses or whenever visibly soiled. A recent report indicates that directed misting application of a peroxygen disinfectant for environmental decontamination is effective in veterinary settings. When cleaning, avoid generating dust that may contain pathogens by using central vacuum units, wet mopping, dust mopping, or electrostatic. Surfaces may be lightly sprayed with water prior to mopping or sweeping. Areas to be cleaned should be appropriately ventilated.

3. Decontamination and spill response

Spills and splashes of blood or other body fluids should be immediately sprayed with disinfectant and contained by dropping absorbent material (e.g., paper towels, sawdust, cat litter) on them. A staff person should wear gloves, a mask, and protective clothing (including shoe covers if the spill is on the floor and may be stepped in) before beginning the clean-up.

5. Veterinary medical waste

Veterinary medical waste is a potential source of zoonotic pathogens if not handled appropriately. Medical waste is defined and regulated at the state level by multiple agencies, but may include sharps, tissues, contaminated materials, and dead animals. The local and/or state health departments and municipal governments should be consulted for guidance.

Many important zoonotic pathogens are transmitted by rodents or insect vectors. The principles of integrated pest management (IPM) are central to effective prevention and control.

IPM practices include:

• Sealing entry and exit points into buildings. Common methods include the use of steel wool, or lath metal under doors and around pipes

• Storing food and garbage in metal or thick plastic containers with tight lids

• Disposing of food-waste promptly

• Eliminating potential rodent nesting sites (e.g., hay storage)

• Maintaining snap traps throughout the practice to trap rodents (check daily)

• Removing sources of standing water (empty cans, tires, etc.) from around the building to prevent breeding of mosquitoes

• Installing and maintaining window screens to prevent entry of insects into buildings

7. General hospital biosecurity guidelines

• Wash hands before and after each animal contact.

• Wear gloves when handling animals when zoonotic diseases are on the differential list of

diagnoses.

• Minimize contact with hospital materials (instruments, records, door handles, etc.) while

hands or gloves are contaminated.

• Change outer garments when soiled by faeces, secretions, or exudates.

• Clean and disinfect equipment (stethoscopes, thermometers, bandage scissors, etc.) with

0.5% chlorhexidine solution after each use.

• Clean and disinfect examination tables and cages after each use. • Clean and disinfect litter boxes and dishes after each use.

• Place pets with suspected infectious diseases immediately into an examination room or an isolation area upon admission into the hospital.

• When possible, postpone until the end of the day any procedures using general hospital

facilities like surgery and radiology.

D. General measures

1. Employee immunization policies

The veterinarian and supporting staff must be immunized prophylactically against some of the diseases and infections.

a. Rabies

Veterinary personnel who have contact with animals should be vaccinated against rabies.

Pre-exposure rabies vaccination consists of three doses of a licensed human rabies vaccine

administered on days 0, 7, and 21 or 28. In addition to pre-exposure rabies vaccination, the rabies antibody titer should be checked every two years for those in the frequent risk category, including veterinarians and their animal handling staff.

b. Tetanus

All staff should have an initial series of tetanus immunizations, followed by a booster

vaccination every 10 years. In the event of a possible exposure to tetanus, such as a puncture wound, employees should be evaluated by their health care provider; a tetanus booster may be indicated.

c. Seasonal Influenza

Veterinary personnel are encouraged to receive the current seasonal influenza vaccine,

unless contraindicated. This is intended to minimize the small possibility that dual infection of an individual with human and avian or swine influenza virus could result in a new hybrid strain of the virus.

2. Staff training and education

Staff training and education are essential components of an effective employee health program. All employees should receive education and training on injury prevention and infection control at the beginning of their employment and at least annually. Additional in-service training should be provided as recommendations change or if problems with infection control policies are identified. Training should emphasize the potential for zoonotic disease exposure and hazards associated with work duties, and include animal handling, restraint, and behavioral cue recognition. Staff participation in training should be documented.

Recommendation: education of higher risk individuals about zoonotic diseases

Education of pet owners at higher risk of infection is essential in helping to prevent the severe syndromes of zoonotic diseases that may occur in these individuals. It is critical that higher risk individuals are aware of the risks of owning a pet and are disposed to discussing their questions about zoonotic diseases with their veterinarian and physician. Educational materials aimed at higher risk clients or patients should be available at veterinarians’ and physicians’ offices to help encourage these individuals to discuss zoonotic diseases. Veterinarians should provide intake forms to clients inquiring about higher risk status of household members in addition to medical history of the pet.

Recommendation: collaboration between veterinarians, physicians, and public health

agencies

It is also vital that regular communication and collaboration occur between veterinarians, physicians, and public health agencies. The three groups have necessary roles to play in education and prevention of zoonotic diseases but have contact with the public in different settings and for different reasons. Public health agencies could serve as a catalyst and a resource for the improvement of education and prevention of zoonotic diseases in their communities. Public health agencies should meet regularly with veterinarians and with physicians in the community to discuss ways in which they could better assist with zoonotic diseases and how to implement these ways. Public health agencies should also increase their involvement with both professions by providing educational materials.

Recommendation: education of veterinarians and physicians

Veterinarians and physicians must maintain a high level of knowledge about zoonotic diseases to be in a position to educate clients or patients and to be involved in prevention of zoonotic diseases. Continuing education courses on zoonotic diseases need to be regularly available and need to emphasize the importance of zoonotic diseases. Joint continuing education programs for veterinarians and physicians would provide excellent opportunities to establish communication formats between the two professions.

Reference:on request.