PRINCIPLE & PRACTICES OF ARTIFICIAL INSEMINATION (AI) IN POULTRY FOR COMMERCIAL LAYER POULTRY BREEDING

Artificial insemination (AI) is the most widely used reproductive technology in the livestock industry. Its adoption in poultry species has increased in popularity, especially in the western countries for research and commercial purposes. Artificial insemination (AI) technology has allowedfor the rapid spread of genetic material from a small number of exceptional males to a huge number of females in the chicken industry. To ensure theoptimum fertility, the artificial insemination procedurein chickens requires exceptional quality semen that should be inseminated extremely close to the female’ssperm storage tubules.Depending on the volume andconcentration of sperm, one cock’s sperm caninseminate 5 to 10 hens. Synthetic insemination canboost poultry fertility as compared to traditional mating. A clean semen sample of sufficient volume isrequired on a regular basis to execute artificial insemination correctly.Finally, assisted reproductivetechniques have a wider use and the potential toreduce costs while increasing geometricallyproductivity and production in case of size differencebetween male and female chickens.

Artificial insemination (AI) is widely used to overcome low fertility in commercial turkeys, which results from unsuccessful mating as a consequence of large, heavily muscled birds being unable to physically complete the mating process. This is a serious and costly problem in the production of commercial turkey hatching eggs. In most commercial chicken production systems in the USA, it has not been necessary to implement AI programs because natural mating results in adequate fertility levels, but AI is routinely used in special breeding work and research. However, as managing commercial broiler breeders to maximize fertility becomes more challenging, the use of AI in commercial poultry operations outside the USA is becoming more common. Certainly, the use of AI in chickens, as in turkeys, can improve fertility; however, the cost of implementing AI on a large scale is often cost prohibitive.

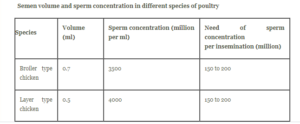

Collecting semen from a chicken or turkey is done by stimulating the copulatory organ (the phallus) to protrude by massaging the abdomen and the back over the testes. This is followed quickly by pushing the tail forward with one hand and, at the same time, using the thumb and forefinger of the same hand to apply pressure in the area and to “milk” semen from the ducts of this organ. Semen flow response is quicker and easier to stimulate in chickens than in turkeys. The semen may be collected with an aspirator (turkeys) or in a small tube or any cup-like container. In turkeys, the volume averages ~0.35–0.5 mL, with a spermatozoon concentration of 6 to >8 billion/mL. In chickens, volume is 1–2 times that of turkeys, but the concentration is about one-half. Collected semen is usually pooled and diluted with an extender before use.

Chicken and turkey semen begins to lose fertilizing ability when stored >1 hr. Liquid cold (4°C) storage of turkey and chicken semen can be used to transport semen and maintain spermatozoal viability for ~6–12 hr. This short-term storage of semen is common in turkeys, while not as common in chickens. When using liquid cold storage for >1 hr, turkey semen must be diluted with a semen extender at least 1:1 and then agitated slowly (150 rpm) to facilitate oxygenation; chicken semen should be diluted and then cooled—agitation is not necessary. Chicken and turkey semen may be frozen, but reduced fertility limits usage to special breeding projects. Under experimental conditions, fertility levels of 90% have been obtained in hens inseminated at 3-day intervals with 400–500 million frozen-thawed chicken spermatozoa.

Several commercial semen extenders are available and are routinely used, particularly for turkeys. Extenders enable more precise control over inseminating dose and facilitate filling of tubes. Results may be comparable to those using undiluted semen when product directions are followed. Dilution should result in an insemination dose containing ~300 million viable spermatozoa for turkeys. However, the number of spermatozoa inseminated will range from 150–300 million viable cells depending on the age of the turkey hens inseminated. In chickens, the number of diluted semen inseminated will range from ~100–200 million sperm cells per insemination. Producers usually determine the spermatozoa concentration and dilute the semen to obtain the appropriate sperm cell concentration for either the turkey or chicken.

For insemination, when holding the hen upright, pressure is applied to the abdomen around the vent, particularly on the left side. This causes the cloaca to evert and the oviduct to protrude, so that a syringe or plastic straw can be inserted ~1 in. (2.5 cm) into the oviduct and the appropriate amount of semen delivered. As the semen is expelled by the inseminator, pressure around the vent is released, which assists the hen in retaining sperm in the vagina or oviduct. When inseminating undiluted turkey semen, the high sperm cell concentration allows for 0.025 mL (~2 billion spermatozoa) to be inseminated at regular intervals of 7–10 days, yielding optimal fertility. In chickens, because of the lower spermatozoon concentration and shorter duration of fertility, 0.05 mL of undiluted pooled semen, at intervals of 7 days, is required. The hen’s squatting behavior indicates receptivity and the time for the first insemination. For maximal fertility, inseminations may be started before the initial oviposition in turkeys, whereas this is not necessary in chickens. Fertility tends to decrease later in the season; therefore, it may be justified to inseminate more frequently or use more cells per insemination dose as hens age.

AI in chicken requires one to understand the basic anatomy and physiology of the hen’s and the cock’s reproductive tract. AI involves the deposition of semen into female reproductive tract manually. It starts with the collection of the semen from the male and its evaluation in terms of motility, viability and concentration followed by its deposition into female reproductive tract. One must be technically competent with the semen collection and deposition procedures in order to achieve effectiveness in producing fertilized eggs. Males can produce semen as early as 12 weeks of age, depending upon body size and lighting programme. However, sperm from such roosters is rarely viable and effective; maturity does not develop until birds are around a minimum of 18 weeks of age. So the cocks from 22 or 24 weeks of age are used for semen collection. Semen consists of spermatozoa and seminal plasma. Fowl semen is generally highly concentrated (3 to 8 billion spermatozoa per ml for broiler fowl). The natural colour of poultry semen is white or pearly white. Heavy breed male can produce 0.75 to 1 ml semen and light breed male can produce 0.4 to 0.6 ml of semen. Chicken semen begin to lose fertilizing ability when stored >1 hour. Liquid cold (4°C) storage of chicken semen can be used to transport semen and maintain spermatozoa viability for ~6–12 hours. Semen is collected 4–6 times in a week. Although every day semen collection will not change the fertilizing capacity but the volume of semen will be low. Inseminations should be carried out on two consecutive days at the first week and then once each week thereafter while fertile eggs are required. As poultry semen has a very limited life, insemination of hens should be complete within one hour of semen collection. It is a good idea to carry out the operation at the same time each day, the best time being between 2.00 and 4.00 pm. The reason for this is that during the morning, most hens have an egg in the oviduct, thus obstructing the free passage of semen to the ovary. Another point in favour of inseminating the hens in the afternoon is that it is generally cooler and the hens are less likely to be affected by heat, particularly in late spring. Equipment needed for AI: small glass funnel with stem plugged with wax, inseminating syringe, wide mouthed glass vial, small pyrex semen cup, large flask to hold water at 180°C to 200°C range for short time holding of semen.

Semen collection:

The first step in AI program is manual collection (milking) of the semen. A team of two members should be involved in semen collection, one for restraining the male and the other for collecting semen. The bird should be held in a horizontal position by a person at a height convenient to the operator who is attempting to collect the semen. To collect semen the operator should place the thumb and index finger of the left hand on either side of the cloaca and massage gently. By his right hand the operator should hold a collecting funnel and with the thumb and index finger massage the soft part of abdomen below the pelvic bones. Massage should be rapid and continuous until the cock protrudes the papilla from the cloaca. Once the papilla is fully protruded, the previously positioned thumb and index finger of the left hand are used to squeeze out the semen in to the collecting funnel. Avoid contamination of semen with faeces and feather. Semen should be evaluated after collection. Normal colour of the semen in pearly white or cream coloured. Yellow semen and semen contaminated with blood, urates, faeces or other debris should be avoided. Semen should not be allowed to come in contact with water. If debris or contaminants are observed in pooled semen, carefully aspirate contaminates from the sample before mixing with additional diluent with the semen. Diluted semen should be kept in a cooler or refrigerator (3 to 12°C) to cool down. Chicken semen begins to lose fertilizing ability when stored >1 hr. Liquid cold (4°C) storage semen can be used to transport semen and maintain spermatozoal viability for ~6–12 hr. Chicken semen may be frozen, but reduced fertility limits usage to special breeding projects.

Insemination:

All equipment to be used for insemination should be thoroughly cleaned and dried before use. Insemination must be carried out when majority of the birds have completed laying since a hard shelled egg in the lower end of the oviduct obstructs insemination and lowers fertility. In practice, inseminating chicken after 3 pm obtained better results. It is difficult to inseminate non-laying hens. Usually insemination is done when the flock reaches 25% egg production. Hens are inseminated twice during first week, then at weekly intervals. Under experimental conditions, fertility levels of 90% have been obtained in hens inseminated at 3-day intervals with 400–500 million frozen-thawed chicken spermatozoa. In chickens, the number of diluted semen inseminated will range from ~100–200 million sperm cells per insemination. In chickens, because of the lower spermatozoon concentration and shorter duration of fertility, 0.05 mL of undiluted pooled semen, at intervals of 7 days, is required. The hen’s squatting behavior indicates receptivity and the time for the first insemination. Fertility tends to decrease later in the season; therefore, it may be justified to inseminate more frequently or use more cells per insemination dose as hens age. Procedure: For insemination hen is held upright by the legs with the left hand down and tail tucked back and against the operator chest. The thumb of the right hand is placed against the upper lip of the vent then with a rounding motion abdomen muscles are pressed, particularly on the left side. Do not squeeze with fingers but apply pressure evenly with the palm of the hand. This causes the cloaca to evert and the oviduct to protrude, the second operator inserts the syringe or plastic straw ~1 inch (2.5 cm) into the oviduct and the appropriate amount of semen is deposited at the junction of vagina and uterus. As the semen is expelled by the inseminator, pressure around the vent is released, which assists the hen in retaining sperm in the vagina or oviduct.

Advantages :

Some of the advantages of artificial insemination in the poultry are: 1. Normally one cockerel can be mated to six to ten hens. With artificial insemination this mating ratio could be increased fourfold. This way one male of high genetic merit for a particular trait of interest can be used to serve more females. 2. Older males having outstanding performance can be used for several generations whereas under natural mating their useful life is limited. 3. Valuable male birds having the leg injury can still be used for artificial insemination. 4. When there is poor fertility caused by preferential mating, it can be eliminated. 5. Although cross breeding is very successful under natural conditions, but sometimes there is a kind of colour discrimination as some hens will not mate with a male of a different colour unless they have been reared together. In such condition AI helps in successful cross breeding. 6. AI allows for incompatible individuals to mate; incompatibility arises when males are heavier than females and under natural mating this may result to injury of the females. 7. AI allows for better use of the cage feeding system in hatchery operations, especially when dealing with large number of females that are required to lay fertilized eggs.

Male chicken reproductive physiology

Unlike mammalian males, who have their reproductive organs outside of the body cavity, the avian male reproductive system is fully inside the bird, just anterior to the kidneys, and linked to the dorsal body wall (Brooks, 1990). As a result, spermatogenesis occurs at a temperature of 41 degrees Celsius in birds, opposed to 24-26 degrees Celsius in mammals’ scrotum (Nickel et al., 1977). One of the most fascinating aspects of birds is that their sperm cansurvive at body temperature. Male reproductive organsare found on the exterior of the body becausemammalian sperm does not survive at bodytemperature (Brooks, 1990). Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone (GnRH) secretionfrom the hypothalamus, Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle Stimulating Hormone (FSH) secretionfrom the anterior lobe of the pituitary, and release of gonadal steroids all contribute to sperm production. LH stimulates the production of progesterone, whichis then transformed to the male sex hormonetestosterone, via acting on the Leydig cells in thetestes (Senger, 2003). Testosterone is required for spermatogenesis in the seminiferous tubules, but highamounts of LH cause the Leydig cells to becomeunresponsive (Senger, 2003). Sperm development canbe divided into three processes: spermatocytogenesis, spermiogenesis, and spermiation. The weights of thetestes were more closely associated with body sizethan with the level of Sperm production. The first stepof spermatogenesis takes place on the perimeter of thespermatogonia-lined seminiferous tubules (Zlotnik, 1947). Spermatogonia are diploid mitoticallyproliferating cells that create spermatocytes andmaintain a steady population of stem cells for spermatogenesis. The seminiferous tubules in birds are structured as anetwork of interconnected ducts that discharge into therete testis after the semen is formed (Tingari, 1972). Acoiled tube, the vas deferens, emerges from eachepididymis and travels posteriorly, attaching to thedorsal body wall until terminating in a tiny phallus inthe cloaca (Nickel et al., 1977). The vas deferens, likethe whole duct, enlarges just before its termination andacts as a storage place for spermatozoa. Each vasdeferens has a tiny papilla at the end that ejects thesperm into the cloaca (Nickel et al., 1977). Several tiny folds in the ventral cloaca get engorged withlymphatic fluid and protrude during sexual stimulation, generating a trough-like structure tocontrol the passage of semen (Nishiyama, 1955). Earlier spermatozoa leaves the rete tubules, structural differentiation is assumed to be complete (Tingari, 1973). Because sperm motility is obtained in the vasdeferens, early investigations indicate that spermextracted from the testis or epididymis of the cockwere capable of producing fertility at a very low level. Total transit time from the testes to the terminal regionof the vasa deferential has been estimated to bebetween 1 and 4 days (Munro, 19). Semen is a mixtureof sperm cells and lymph fluid (Nishiyama, 1955).

Secondary sexual characteristics in Cockerel

Secondary sex characteristics are acquired as roosters mature as a result of hormonal secretions from the testes, which are regulated by gonadotrophin secretion from the anterior pituitary gland and gonadotrophin releasing hormones (GnRH) secretion from the hypothalamus (Etches, 1996). Comb, plumage, and wattle development are examples of male secondary sex characteristics. Although capons and masculinized females will make poor attempts to emulate the intact male, androgens are also responsible for the full production of the rooster’s unique voice (Etches, 1996).Androgens are required to induce growth of the comb and wattles in roosters. In both sexes, the development of the comb coincides with increased plasma concentration of androgens (Etches, 1996). Mashaly and Glick (1979) speculated that dihydrotestosterone may be more important than testosterone in driving comb growth. Rath et al. (1996), on the other hand, found that testosterone increased comb weight.Cocks typically begin producing sperm at the age of 16 weeks, however the fertilizing potential of the sperm is limited. As a result, cocks as young as 22 or 24 weeks are used for semen collecting. Whi pearly white is the natural color of fowl sperm. Males of heavy breeds can generate 0.75 to 1 ml of sperm, whereas light breed males can produce 0.4 to 0.6 ml. A man can be utilized for semen collection three times a week with a one-day break between each session. Although daily sperm collection will not affect fertilization capacity, the volume of sperm collected will be low.

Semen Characteristics in Chicken

Semen is made up of spermatozoa and seminal plasma. Fowl sperm is often quite concentrated (3 to 8 billion spermatozoa per ml for broiler fowl). This is due to birds lacks extra reproductive systems, resulting in a limited amount of seminal plasma. The seminal plasma is produced by the testes and excurrent ducts. After ejaculation, a lymph-like fluid of cloacal origin may be added to the semen in various amounts. When clear fluid is added to sperm after ejaculation, it acts as an activating medium for previously non-motile spermatozoa, ensuring their passage from the deposition to the sites of sperm storage tubules in the utero-vaginal junction of the hen’s oviduct. The average semen ejaculate amount measured was 0.6 ml, with the cockerel producing between 0.1 and 1.5 ml per ejaculation (Cole and Cupps, 1977). At different periods, different cockerels of the same species produce varied quantities of semen(Anderson, 2001). Using the abdominal massagetechnique, the average volume ejaculated is around0.25ml (Gordon, 2005). The average spermatozoaconcentration is 3.5 million per milliliter of sperm. Sperm movement characteristics include straight-linevelocity, curved velocity, and average path velocity. Burrows and Titus (1939) revealed that a link betweenthe size of the testis and the volume of semenproduced. From 16 to 44 weeks of age, males with thelargest testes produced the most semen (de Reviersand Williams, 1984). Big males, in general, have largetestes, hence broiler breeder males generate moresperm than Leghorn males (de Reviers and Williams, 1984). The quality of the spermatozoa is a more important limiting factor than the number of times they areinseminated. Semen volume and concentration, spermviability, and sperm motility are typically used todefine the quality of avian sperm (Parker et al., 2000). Brown and McCartney (1983) showed, however, that neither the volume of semen collected nor the weight of the testes had any effect on egg fertility or hatchability. In natural mating flocks, fertility relatesirregularly with sperm concentration and volume. (Wilson et al., 1979). The quality of sperm is alsoaffected by how they are handled and how long theyare stored (Wishart, 1995). Sperm motility, spermmetabolism, and the fraction of defective or deadsperm have all been linked to fertility (McDaniel andCraig, 1959).

Semen collection Techniques from Cocks

A clean semen sample of sufficient volume is requiredon a regular basis to properly perform artificial insemination. The oldest method of semen collectionrequired the cockerel to mate with a hen, after whichthe hens were killed and the semen was surgicallyremoved from the oviduct. In turkeys, domestic fowls, guinea fowls, quails and pheasants quails), andpheasants, the erection of the copulatory organ and theejaculation reflex occur simultaneously in response tomassage, and the majority of the spermatozoa areobtained in the first ejaculate(Lake and Stewart, 1978, Marks and Lepore, 1965). In light breeds of chicken, the average volume of semen per collection ranges from 0.05-0.50 ml, whilein heavy breed males, it ranges from 0.1-0.9 ml (Lakeand Stewart, 1978). The volume of semen in light- weight turkeys is 0.08-0.30 ml, while it is 0.1-0.33 ml in heavy-weight males (Lake and Stewart, 1978). The capacity of spermatozoa from chickens up to three years old to fertilize is the same; however, the volume of spermatozoa diminishes with age. To ensure good quality semen, male birds must be routinely trained for semen collection for several days prior to the actual date of artificial insemination application. Therefore, feed should be stopped 12 hours before semen collection to ensure clean semen collection samples. It’s vital to remember that the fraction of naturally degenerating spermatozoa in the vas deferens grows as the time between semen collections gets longer. This is due to the re absorption of spermatozoa (Tingari and Lake, 1972). Semen should be collected from males at a certain frequency during the mating season to ensure a steady supply of good quality semen, though this varies by breed and species. The optimum output of spermatozoa was maintained at a thrice weekly frequency (alternating days), resulting in good fertility in chickens (Lake and Stewart, 1978).

Semen Evaluation

The examination of semen quality serves two purposes: first, to guarantee that only males producing high-quality sperm are kept on the farm, and second, to evaluate the concentration of spermatozoa and the volume of semen. This enables estimates to be done for the proper dilution to produce 80-100 million spermatozoa per insemination dose. Using sperm concentration to calculate the quantity of sperm per insemination dosage and as a measure of sperm quality has various advantages (Senger, 2003). The typical sperm concentration in domestic cockerel sperm of 5 billion sperm cells per milliliter (Gordon, 2005), whereas Hafez and Hafez (2000) reported 3-7 billion sperm cells/ml. Sperm motility is an indicator of live sperm and of the quality of the semen sample. Fresh and diluted sperm are used to test sperm motility, which is usually done under a light microscope (Hafez and Hafez, 2000). In domestic fowls, sperm motility is a major factor of fertility (Donoghue et al., 1998). The visual examination of sperm must, however, be overlooked (Peters et al., 2008). A good-quality semen sample is thick and pearly white in color (Cole and Cupps, 1977), and any other color indicates contamination; for example, yellow and green-colored semen indicate faecal or urine contamination (Lake, 1983). The presence of blood is indicated by a brownish red pigment or a reddish color (Etches, 1996).Domestic fowl semen, onthe other hand, varies in consistency from a denseopaque suspension to a watery/transparent fluid(Mohan and Moudgal, 1996). The morphology of spermatozoa can be used to assess the quality of sperm. Blesbois (2007) described that a technique for examining the morphology of cockerel sperm usingeosin-nigrosin staining. Traditionally, spermevaluation has been done by a laboratory technicianpeering under a microscope and manually countingsperm, progressing motility (typically given a valueranging from 1 to 4), and sperm quality (generallygiven a grade ranging from 1 to 4) and morphology of spermatozoa (damage and defects). Theseobservations were entirely personal. In chickens, the CASA system was used incombination with a phase contrast microscope (NikonEclipse model 50i; negative contrast) and Sperm ClassAnalyzer software to quantify sperm motility andconcentration. Straight-line velocity (VSL), curvilinear velocity (VCL), and average path velocitywere among the sperm movement characteristicsstudied by CASA. Based on their general velocity, spermatozoa were classified as slow (10 m/sec), medium (10-50 m/sec), or rapid (>50 m/sec).

Hen insemination synthetically

Semen is frequently deposited in the shallow locationin the hen’s vagina during natural copulation. For optimum fertilization of eggs laid daily in successionby hens throughout the following week, it is requiredto evert the distal section of the oviduct (vagina) anddeposit the semen to a depth of 2-4 cm during artificial insemination. Chicken sperm is usually inseminated at a depth of 2-3 cm in the vaginal canal (Artemenko andTereshchenko, 1992). The actual insemination of thehen can be conducted by two people after good semensamples have been obtained (Quinn and Burrows, 1936). One person applies the proper pressure on theleft side of the abdomen so that the hen turns insideouther vaginal orifice through the cloaca. At the sametime, the semen is deposited by the second person to adepth into the vaginal orifice concurrently with thewithdrawal of pressure on the hen’s abdomen. Insemination can be done with sterile straws, syringesor plastic tubes. The sperm is kept here for several days or weeksbefore being used in the fertilization process. According to Hafez and Hafez (2000), sperm spends avery brief time in the female tract in mammals, but can remain much longer in the oviduct in hens and turkeys before fertilizing the egg yolk cell (up to 32 days in chickens and 70 days in turkeys). Spermatozoa will migrate from the SSTs to a second storage location (sperm nests) at the junction of the magnum and infundibulum in the upper section of the oviduct (Aisha and Zain, 2010). The entrance of an ovum into the infundibulum causes spermatozoa to be released from sperm nests for fertilization to occur (Aisha and Zain, 2010).

Timing of Insemination

In both artificially and naturally mated hens, the time- of-day insemination is performed has a major impact on fertility. The occurrence of hard-shelled eggs in the uterus of hens in the evening is uncommon. As a result, inseminations in the afternoon or evening produce higher fertility than those in the morning (Christensen and Johnston, 1977; Aisha and Zain, 2010). The presence of hard-shelled eggs in the uterus of hens at or near the time of AI results in a reduction in fertility. The majority of spermatozoa inseminated in chickens and turkeys within 1-3 hours after oviposition are removed by the contraction of the vaginal involved in the process of oviposition (Brillard and Bakst, 1990).

Semen collection procedures.

Prior to semen collection, cocks need to be trained and this is achieved through abdominal and back massage for about a minute for 3 days, consecutively. The abdominal massage method is the most commonly used since it is non- invasive and has minimal stress on the cock.

The procedure involves restraining the male, followed by gentle but rapid stroking of the abdomen and back region (testes are located in this region) towards the tail. This stimulates the copulatory organ causing it to protrude. At this point, the handler quickly pushes the tail forward with one hand and, at the same time, using the thumb and forefinger of the same hand to gently squeeze the region surrounding the sides of the cloaca to “milk” semen from the ducts of the copulatory organ.

Semen may then be collected in a small tube or any cup-like container. This procedure is repeated twice, once a day; an additional round may cause damage to the testes and cloacal region. The volume of semen that can be collected from a single cock ranges from about 0.7 to 1.0 ml, with a spermatozoon concentration of 3 to 4 billion/ml. However, the quantity of semen depends on genetics and environmental factors such as age, body weight, season and nutrition.

The degree to which the male will respond to the abdominal massage technique and the pressure applied on the ejaculatory ducts will also influence the quantity of semen produced. Chicken semen begins to lose fertilizing ability when stored for more than 1 hour; therefore it must be deposited in the hen within the 1 hour of collection. In the case of short-term storage and transportation of the semen, it is necessary to use liquid cold (4⁰c) storage to maintain spermatozoa viability for up to 24 hours.

Semen deposition procedure.

Vaginal insemination is commonly used for semen deposition as there are less risks of injury the hen. Preliminary stroking and massaging of the back and abdomen is required to stimulate the hen. This is followed by applying pressure to the left side of the hen’s abdomen around the vent causing evertion of the cloaca hence protrusion of the vaginal orifice.

An inseminator containing the semen is inserted 2.5 cm deep into this opening for semen to be deposited. As the semen is expelled by the inseminator, pressure around the vent is released, so that the oviduct can return to its normal position and draw the semen inwards to the utero-vaginal junction.

Inseminators such as straws, syringes or plastic tubes may be used. During insemination, the volume of semen required per hen is about 0.1ml which contains about 100 to 200 million sperms. Timing of the insemination should be considered. It is best to inseminate hens in the late afternoon (2:00pm and 4:00pm), since in the morning hours hens may have an egg in the oviduct, making it difficult for the sperm to swim up to the ovary.

A significant feature of the reproductive physiology of the hen is her ability to store fertile spermatozoa for up to 14 days in the sperm storage tubules located at the utero-vaginal junction. The tubules release the semen, slowly over time, which swim to the fertilization site and therefore allows for hens to be inseminated consecutively for two days for the first time, and thereafter at regular intervals of 14 days.

Twenty-four hours after insemination, egg-breakout analysis is carried out to determine egg fertility. Currently, the Smallholder Indigenous Chicken Improvement Program (InCIP) – research unit at Egerton University offers training to interested farmers on the artificial insemination in poultry.

The training does not require any background on poultry science, just an individual’s interest. This is because the training covers the fundamentals of the reproductive anatomy and physiology of the male and female, at a theoretical and practical level.

Thereafter, the trainees are taken through a practical lesson on semen collection and deposition techniques, and egg fertility analysis. The training takes a period of two weeks and the expectation at the end of it is that individuals have the capacity to carry out semen collection from males (abdominal massage, semen milking and semen handling), semen deposition in females (cloacal evertion, semen deposition) and differentiate fertile eggs from infertile eggs.

Dose and Frequency of Insemination

Egg fertility in domestic chickens is affected by the age of the bird, the number of sperm, and the type of hen either broiler or layer (Talebi et al., 2009). By the age of 52 weeks, turkey spermatozoa had lost 20% of their motility. According to these researchers, males who had AI between 32-35 and 39-42 weeks of age had better fertility rates than those who had it after 44- 47 weeks of age (93.90 and 97.50 percent vs. 81.80 percent fertility respectively). The quality of male sperm has diminished throughout the course of 44-52 weeks. Semen quality was higher in 35–42-week turkey males than in 63–73-week turkey males (Slanina et al.,2015).Young chickens inseminated at weekly intervals with moderate sperm doses (125 million) had high fertility (93.3 percent), but large sperm doses (250 million) in old hens were unable to maintain fertility at a similar level to young hens(Brillard and McDaniel,1986). This indicated that older chickens had a higher incidence of sperm loss in sperm host glands than younger hens.

Factors affecting semen production in male chicken

The collection, quality, and fertility of birds’ sperm areaffected by their age, season, lighting schedule, bodyweight, diet, management, and spermatogenesis(Mohan et al., 2016). Individuals from different strainsand breeds, as well as different poultry species, haveinherent variances in semen production (Lake, 1983). With the exception of mammals, cockerel sperm istypically immotile before ejaculation (Hafez andHafez, 2000). Various factors can influence spermproduction (Anderson, 2001) and a thoroughunderstanding of cockerel reproduction physiology isessential to appreciate male fertility. The male’s spermproduction can be influenced by a variety of external and internal factors. The pituitary, testes, and to someextent extrinsic factors influence male reproductiveactivities. External factors affecting cockerel reproductive efficiency can be divided into twocategories: direct influence of diet, management, andnormal physiological processes that regulatespermatogenesis, and factors that influence the degreeto which the male will respond to the massagetechnique during semen collection (Maule, 1962).

Applicability of Artificial Inseminationin Poultry

Artificial insemination is a valuable approach toenhance the reproductive success of birds, especiallybroiler breeders and turkeys with low fertility due totheir huge body weight. Despite the fact that AI is awell-developed technique in cattle, it is less so inpoultry due to the lack of a standard method for storing poultry sperm for a lengthy period of time. Semen can be collected and utilized for inseminationimmediately using current processes, with or without dilution, utilizing semen diluents at a 1: 2 ratios. Onecock’s sperm can inseminate 5 to 10 hens, dependingon the volume and concentration of sperm. Theprocess of synthetic insemination entails vaginal eversion and semen deposition.Artificial inseminationis used extensively with freshly collected semen. It isused more intensively for turkey breeding becausemating is difficult due to large size. Freshly collectedchicken semen was among the first type of semen tobe frozen. However, cryopreserved poultry sperm areless fertile and freezing poultry sperm still isexperimental. This procedure consists of collectingsemen from males and inseminating into females. Themajor use of Artificial insemination is in heavy birdswhose fertility is generally low under pen mating. It Adopting artificial insemination. as well as service of a valuable male can be extended can increase fertility. The practice of Artificial insemination requires some training on the part of both operator and the male. It is a valuable technique in avian species. It is ordinarily practiced when the flock presents an apparent fertility problem. Better fecundity has been obtained by the use of artificial insemination, better in many instances, than that obtained by natural mating. The artificial insemination of domestic fowl is not widely used on commercial farms.

Merits of Artificial Insemination Over Natural Mating

Artificial insemination has long been viewed as a beneficial tool in the chicken industry (Benoffet al., 1981). One of the advantages of this technology over natural mating is the efficient use of males. As a result, the cost of artificial insemination is cut in half right away by reducing the number of cocks needed (Benoffet al., 1981). Artificial insemination may become effective in broiler breeder management and in resolving compatibility concerns if broiler breed fertility continues to diminish due to male selection for growth and compatibility issues between large and small breeds (Reddy, 1995). In addition to its breeding utility, artificial insemination is important in the prevention of venereal infections. Artificial insemination can make the most of better male’s services by using semen diluent, which is not achievable with natural mating. From an economic standpoint, diluents minimize the number of males necessary for artificial insemination, resulting in lower feed costs, as well as reduced space, maintenance, and operating costs. Natural mating limits the number of males to females to roughly 1:10, however artificial insemination allows breeders to serve 100 hens from a single male. Males were used more frequently as a result of this. Fresh sperm (5.34 x 109 sperm/ml) taken from a cockerel (0.5 ml) can be inseminated in to 70 hens every day following dilution with CARI diluent (1:6), giving 38 million sperm per dosage for synthetic insemination(Mohan and Sharma (2017). Fertility rates of over 90% or higher can be reached in these ways around 280 hens could be covered by using a single male on alternate days (four times a week), whereas natural mating preserved the cockerel to hen ratio at 1:8. In avian species, Artificial insemination produces more fertile offspring than normal mating (Mohan et al., 2016).Even though natural mating can result in good fertility, rates can be improved even more by including artificial insemination into thereproductive process (Gee et al., 2004). Because of thebenefits of overall fertilization rate and hatchability, the cost per unit of day-old chicks hatched is reduced(Brillard, 2003). If avian artificial inseminationapproaches are expanded to endangered birds, similar benefits in terms of reproductive success can beenvisaged.

CARI Poultry Semen Diluent for Artificial Insemination Technology

Poultry semen is highly concentrated and low in volume. It is further concentrated after ejaculation due to evaporation of water from semen at room temperature that makes impractical to handle it in undiluted form. This event leads to the killing of spermatozoa in fresh semen that requires immediate dilution of semen for achieving higher fertility in poultry through artificial insemination (A.I.) technology. Technology Details To handle the above-said problem of poultry semen and its maximum utilization using A.I. technology, dilution of semen is the only alternate. This is the reason we have developed a “CARI poultry semen diluent”. The diluent is a media which provides an ideal environment for the survival of spermatozoa outside of the body. Using this diluent, highly concentrated chicken/ poultry semen from a single valuable or proven sire can be diluted several folds for inseminating a large number of females through the application of A.I. which is not possible under natural mating. In this way, diluent will increase semen volume thereby permit the uniform distribution of spermatozoa in media resulted in very good fertility by AI in hens. In addition, diluent prolongs the sperm survival of semen in vitro condition (24-48 hrs.). Using the poultry semen diluent, the services of the superior male can be used maximally by A.I. technique. Without the diluent successful application of A.I. is not possible. A.I. is the best tool for genetic improvement. By virtue of the diluent, the technique of A.I. presently is employed as a biggest and cheapest tool for improving the poultry production associated with the reduction of the cost of poultry breeding by the maintenance of less number of males. Using the technique of semen dilution, semen can be preserved for several hours without significant loss of fertilizing ability. This will be very beneficial in transporting the semen of valuable sire of inheritance for high egg and meat yield from one place to another part of the country/world. In India, poultry is 90 % dominated by chicken. Hence, this diluent is mainly targeted to the chicken. However, it also works well in other poultry species like turkey, duck and guinea fowl etc.

Artificial insemination (AI) is the manual transfer of semen into the female’s vagina. Basically, it is a two-step procedure: first, collecting semen from the male and second, inseminating the semen into the female. Artificial insemination was first practiced in America during the 1920’s and then used widely in Australia with the introduction of laying cages during late 1950’s. AI is the method of choice for the geneticist for maintaining the pedigreed mating. Broad breasted turkey was produced by genetic selection, which is physically incapable of natural mating so in such birds AI is the only way of mating. AI is done to minimize the size of male flock in guinea fowl as in guinea fowl one male is used for two-three female.

Some of the advantages of artificial insemination in the poultry are: 1. Increased mating ratio: Normally one cockerel can mated to six to ten hens. With artificial insemination this ratio could be increased fourfold. 2. Older males having outstanding performance can be used for several generations. Whereas under natural mating their useful life is limited. 3. Valuable male birds having the leg injury can still be used for artificial insemination. 4. Elimination of preferential mating: When there is poor fertility caused by preferential mating, it can be eliminated. 5. Successful cross breeding: Although cross breeding is very successful under natural conditions, but sometimes there is a kind of color discrimination as some hens will not mate with a male of a different color unless they have been reared together. In such condition AI helps in successful cross breeding.

ARTIFICIAL INSEMINATION

Day old male parent chicks are supplied dubbed and detoed. Males are reared separately from 0-21 weeks of age. Start with 12% males in case of natural mating and 8% in case of artificial insemination. At the beginning of the breeding season (22 weeks), introduce 8 males per 100 females. Replace weak, lame and sick males promptly. In case of A.I. maintain at least 5% males which can yield about 0.5 ml neat semen per ejaculate with not less than 60% motility. Inseminate females once in 5 days, with 0.03 – 0.05 ml of neat semen: within 30 minutes after collection.

Artificial Insemination (AI) is an important tool to improve the reproductive performance of birds especially broiler breeders where fertility is low due to heavy body weight. Even though AI is well developed technique in cattle, is not so well developed in poultry because no standard technique is available to store poultry semen for a long period. The techniques available at present permits to collect semen and use it for insemination immediately with or without dilution using semen diluent s at 1: 2 ratios.

Semen collected from one cock is sufficient for inseminating 5 to 10 hens depending upon the semen volume and sperm concentration. At farms, where AI is practiced the males are kept separately in individual cages where sufficient space is available for movement of the birds. There should be a team of workers to associate collection and insemination of semen. Frequent changes of personnel in the team may affect the normal behavior of birds. Rough handling should be avoided, if not it may develop fear reaction, which affects the semen volume during ejaculation.

Characteristics of poultry semen

Usually cock start producing semen from the age of 16 weeks but the fertilizing capacity of the semen is low. So, the cocks from 22 or 24 weeks of age are used for semen collection.

The natural color of poultry semen is white or pearly white. Heavy breed male can produce 0.75 to 1 ml semen and light breed male can produce 0.4 to 0.6 ml of semen.

A male can be used thrice in a week for semen collection with a gap of one day. Although everyday semen collection will not change the fertilizing capacity, but the volume of semen will be low.

Semen consists of spermatozoa and seminal plasma. Fowl semen is generally highly concentrated (3 to 8 billion spermatozoa per ml for broiler fowl). This is due to the presence of limited amount of seminal plasma since the accessory reproductive organs are absent in avian species. The seminal plasma is derived from the testes and excurrent ducts.

At the time of ejaculation, a lymph-like fluid (also known as transparent fluid) of cloacal origin may be added to the semen in varying amounts. The addition of transparent fluid to semen at the time of ejaculation act as an activating medium for the previously non-motile spermatozoa, thus ensuring their transport from the site of deposition to the sites of sperm storage tubules in the utero-vaginal junction of the hen’s oviduct.

Equipment’s needed for A.I

- Small glass funnel with stem plugged with wax.

- Inseminating syringe

- Wide mouthed glass vial.

- Small pyrex semen cup

- Large flask to hold water at 180 C to 200 C range for short time holding of semen.

Steps in Artificial Insemination

AI in poultry is a three-step procedure involving semen collection, semen dilution and insemination. The second step may be omitted if ‘neat’ semen (undiluted) is to be used for insemination within 30 minutes after collection.

Semen collection

The first step in AI program is manual collection (milking) of the semen. For semen collection, a team of two members are generally involved, one for restraining the male and the other for collecting semen.

The bird is held in a horizontal position by a person at a height convenient to the operator who is attempting to collect the semen. To collect semen the operator should place the thumb and index finger of the left hand on either side of the cloaca and massage gently.

By his right hand the operator should hold a collecting funnel and with the thumb and index finger massage the soft part of abdomen below the pelvic bones. Massage should be rapid and continuous until the cock protrudes the papilla from the cloaca.

Once the papilla is fully protruded, the previously positioned thumb and index finger of the left hand are used to squeeze out the semen into the collecting funnel. Avoid contamination of semen with faeces and feather.

Semen evaluation at the time of collection

Normal color of the semen in pearly white or cream colored. Yellow semen and semen contaminated with blood, urates, faeces, or other debris should be avoided. Do not allow semen to contact water.If debris or contaminants are observed in pooled semen, carefully aspirate contaminates from the sample before mixing with additional diluent with the semen.Place the diluted semen in a cooler or refrigerator (3 to 12-degree Celsius) to cool down.

Insemination

All equipment used for insemination should be thoroughly cleaned and dry before Use.Insemination must be carried out when majority of the birds completed laying since a hard-shelled egg in the lower end of the oviduct obstructs insemination and lowers fertility.In practice, inseminating chicken after 3 pm obtained better results.It is difficult to inseminate non-laying hens.Usually insemination is done when the flock reaches 25% egg production.Hens are inseminated twice during first week. Then at weekly intervals.

Procedure

Bird is held by the legs with the left hand down and tail tucked back and against the operator chest.The thumb of the right hand is placed against the upper lip of the vent then with a rounding motion press the abdomen muscle.Do not squeeze with fingers but apply pressure evenly with the palm of the hand.When the oviduct is everted, the second operator inserts the syringe into oviduct as far as it is going inside without exerting pressure.The insemination apparatus is introduced into the vagina about 1 inch and semen is deposited at the junction of vagina and uterus.

Dose and frequency of insemination

Chicken: 0.05 ml, once in a week

It has been observed that the males produce more semen of good quality during morning and females produce more fertile eggs when inseminated around 9 p.m.

Conclusion:

The benefits of AI for broilers would include the following: the male: female ratio would be increased from 1:10 for natural mating to 1:25 with AI; with fewer males needed, there would be greater selection pressure on the male traits of economic importance and subsequently greater genetic advancement per generation. It may happen that sometime in the future, research addressing poultry sperm biology and the cellular and molecular basis of oviductal spermatozoa transport, selection, and storage will lead to the following innovations in poultry AI technology: insemination intervals increased to 10–14 days (versus 7-day) with fewer sperm per insemination; in vitro sperm storage for 24–36 h at ambient temperature with minimal loss of sperm viability.

EDITED BY-Dr.Nirbhay Kumar Singh

Assistant Professor

Dept. of Veterinary Anatomy

Bihar Veterinary College

Patna

REFERENCE- 1Shambel Taye and 2Wondmeneh Esatu 1Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR), Debre Zeit Agricultural Research Center, P.O. Box: 32, Bishoftu, Ethiopia 2 International Livestock Research Institute (ILR), Addis Ababa Ethiopia Corresponding author, Email: olyaadshambel@gmail.com