ROLE OF OXYTOCIN IN MILK LET-DOWN IN DAIRY COWS

Compiled & Edited by-DR RAJESH KUMAR SINGH ,JAMSHEDPUR,JHARKHAND, INDIA, 9431309542,rajeshsinghvet@gmail.com

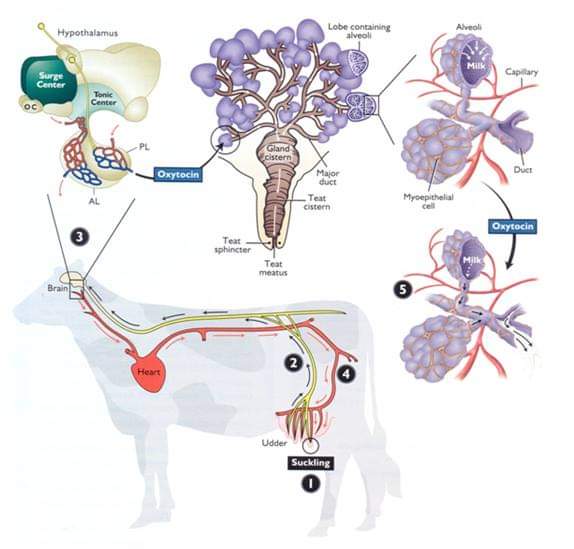

Milk let-down is controlled by unconditioned factors, most notably the response to tactile stimuli provided by a calf rubbing the udder or teat when suckling, or a similar stimulus provided by the milker when foremilking the quarter or otherwise preparing it for being milked. Other, conditioned factors, such as the psychological stimuli provided by the sounds, smells and routine the cow experiences at or around milking time also contribute to milk let-down.

These stimuli result in the release of the hormone oxytocin from the cow’s pituitary gland in the brain into the bloodstream, where it travels to the udder and causes several important processes to occur.

Oxytocin release causes the mass of interconnecting blood vessels at the base of the teat to fill with blood, making the teat more erect and allowing milk to enter it from higher in the udder and pass through the teat. Oxytocin also encourages muscles throughout the udder to act to release milk. Most importantly, the muscle cells around the milk-producing alveoli deep in the udder contract and force the milk into the various ducts in the udder, down into the udder cistern and then into the teat cistern, ready for the milk to be removed by the suckling calf or the milking equipment.

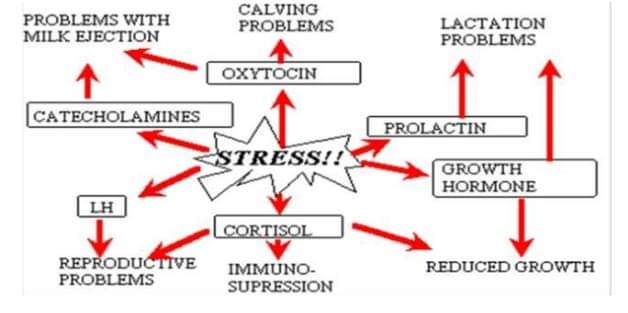

This is why during milking, for efficient let-down cows should be subjected to minimal stress, as this can cause the release of the hormone adrenalin (as a response to stress) which can counter the effect of oxytocin.

The average time between beginning to prepare the cow for milking and the resultant let-down of milk is in the order of 60 to 90 seconds. During the period between milkings, an amount of milk will have already collected in the udder and teat cisterns, and will be released almost immediately upon attachment of the milking equipment. There then follows a period known as lag time, whereupon the oxytocin released into the bloodstream causes the release of milk deep in the udder. If the time between the first stimulus of the udder by foremilking or wiping the teats occurs approximately 60 seconds after beginning the process, the release of milk from higher in the udder will be practically continuous with the first release of milk stored in the teat and udder cisterns.

The release of oxytocin and milk ejection occurrence in response to teat stimulation are crucial for fast and complete milk removal during milking or suckling. The milk ejection reflex can be disturbed at central or peripheral level under different experimental and practical conditions. The central disturbance results in the lack or insufficient ejection of the alveolar milk into the cistern due to inhibited oxytocin release from pituitary into the blood circulation. The important role in the pathophysiological regulation of the inhibited release of oxytocin is played by an opioid system. Endogenous opioids have suppressive effects on oxytocin release under the normal conditions of milk removal. The central inhibition of oxytocin release has often been observed in dairy practice during milking of primiparous cows after parturition, suckling by alien calf, calf removal before milking, milking of cows in the presence of own calf, relocation and milking in an unknown milking place. Peripheral mechanisms are related to the increased levels of catecholamines and/or activation of sympathetic nervous system at the udder level. In conclusion, the release of oxytocin and milk ejection efficiency can be very easily suppressed by many factors. The physiological requirements of dairy cows have to be respected.

Milk let-down and ‘lag time’

The process of milk ‘let-down’ in the cow is of particular interest as the timing of let-down can be used to form an efficient routine to milk cows as quickly and efficiently as possible while minimising any teat damage that can be caused by ‘overmilking’ – when there is a high vacuum but little milk flow – and also by acknowledging that the time immediately following milking is crucial to controlling bacterial entry into the teat as the teat sphincter takes time to close post-milking.

Where a longer or shorter lag time occurs, the milk flow can become bimodal; there is effectively a gap where overmilking can occur, even at this early stage of the milking process. Here, the high vacuum from the milking machine combined with a low or nonexistent flow of milk can cause significant damage to the teat end, making the cow more susceptible to mastitis, and likely also to lengthen the milking time significantly.

During milking, the teat lengthens while the teat canal opens up and becomes shorter, to allow faster removal of the milk from the cistern structures above it. Following milking, the overall teat length shortens, the teat canal lengthens and the teat sphincter begins to close, as the folds of skin around the opening close around one another, creating a tight seal, and the lipidised film around the sphincter stops a column of milk forming through which bacterial entry could occur. A waxy keratin seal begins to form in the teat canal to protect against bacterial entry after milking.

However, the sphincter muscle can take in the order of 20 to 30 minutes to close, and it is during this time that the risk of bacterial entry is greatly increased. This is why post-dip treatments play an important role, and also why cows should not be permitted to lie down for a 30 minute period post-milking.

Milk ejection or let down———–

Milking or nursing alone can empty only the cisterns and largest ducts of the udder. In fact, any negative pressure (vacuum) causes the ducts to collapse and prevents emptying of the alveoli and smaller ducts. Thus, the dam must take an active although unconscious part in milking to force milk from the alveoli into the cisterns. This is accomplished by active contraction of the myoepithelial cells surrounding the alveoli. This process is termed milk ejection, or milk let down . These myoepithelial cells contract when stimulated by oxytocin, a hormone released from the neurohypophysis of the pituitary as a result of a neuro-endocrine reflex. The afferent side of the reflex consists of sensory nerves from the mammary glands, particularly the nipples or teats. Afferent information reaches the hypothalamus, which regulates the release of oxytocin from the neurohypophysis. Suckling the teats by the young or mechanical stimuli of teats at milking are the usual stimulus for the milk ejection reflex, but whether milk is withdrawn from the teat or not, the milk ejection reflex produces a measurable increase in the pressure of milk within the cisterns of the udder.

The milk ejection reflex can be conditioned to stimuli associated with milking routine, such as feeding, barn noises, and the sight of the calf. It can also be inhibited by emotionally disturbing stimuli, such as dog barking, outer loud and unusual noises, excess muscular activity, and pain. Stressful stimuli increase the activity of the sympathetic nervous system, which can inhibit the milk ejection reflex. This inhibition occurs both at the level of the hypothalamus via inhibition of oxytocin release and the level of the mammary gland, where sympathetic stimulation can reduce blood flow and directly counteract the effect of oxytocin on myoepithelial cells.

Oxytocin release typically occurs as a surge within a minute or two after initiation of the reflex by some tactile or environmental stimulus, and the plasma half-life of oxytocin is but a few minutes. Hence, milking or suckling should begin in close association with stimuli known to activate oxytocin release, such as washing the udder and stimulation of the teats. If failure to get an adequate stimulus for milk ejection, possibly because of inadequate preparation before milking, becomes habitual, the lactation period may be shortened by excessive retention of milk in the udder.

Essentially all the milk obtained at any one milking is present in the mammary gland at the beginning of milking or nursing. However, milking does not usually remove all of the milk in the gland. Up to 25 percent of the milk in a gland usually remains after milking. Some of this residual milk can be removed after injections of oxytocin, but the routine use of such injections tends to shorten the lactation period.

Reference-On Request