STRUCTURAL DISORDERS (SURGICAL CONDITIONS ) OF UDDER AND TEATS IN COWS

Compiled & Edited by-DR RAJESH KUMAR SINGH, JAMSHEDPUR, 9431309542,rajeshsinghvet@gmail.com

Surgical conditions of udder and teats are getting much attention now a day as these affects the economy of the dairy farmers of India.. Milk alone contributes around 63% to the total output from livestock. We vets at field level gets several calls from dairy farmers regarding milk let down problems related to udder/teat disorders. So , it has become necessary to refresh our knowledge through social platform related to this. The udder and teats are vulnerable to external trauma or injury because of their anatomical location, increase in size of udder and teats during lactation, faulty methods of milking, repeated trauma to the teat mucosa, injury by teeth of calf, unintentionally stepped on teat, paralysis resulting from metabolic disturbances at parturition. Any disease condition of udder and teats not only causes painful milking but also makes udder and teats prone to mastitis. The diseases of udder can be congenital anomalies are known at the time of first calving but acquired anomalies can affect any stage of lactation. Congenital and acquired surgical conditions of udder and teats can be grouped into three main categories.

A. Conditions of epithelial surface of udder and teats.

B. Conditions of glands and tea cistern or canal.

C. Conditions of teat sphincter.

A. Conditions of epithelial surface of udder and teats

- Supernumerary or extra teats —–

These teats are often seen on the posterior surface of udder and in-between the teat. They may be functional or nonfunctional, functional activity can be determined only after parturition of the animal. They frequently interfere with free milking process and are objectionable on show animals. It has been reported that presence of supernumerary teats

has no significant effect on milk yield, lactation length, age at calving, conception rate and service period. Surgical removals of these teats are best in young animals and in case of older cow in dry condition. Surgery performed under local infiltration analgesia with two elliptical incisions at the junctions of teat and udder and skin wound closed with interrupted suture using nonabsorbable suture m - Bovine ulcerative mammitis (sore teats)—–

The teats become painful due to presence of crakes, traumatic injuries, lesions due to disease conditions such as pox, FMD etc. If these lesions are not treated well in time, the animal will not allow touching the affected teat for milking. These lesions become ulcers in due cource of time and the condition are then known as bovine ulcerative mammitis. Oozing of blood from injured teat causes contamination of milk while milking thereby making it unfit for human consumption. In such cases, sterilized teat siphon should be used to drain the milk out. For treatment of such painful lesions, the wound should be washed with light potassium permanganate solution and then soothing preparation such as iodized glycerin, bismuth iodoform paraffin paste, zinc oxide ointment or antiseptic dressing with soothing emollient may be continued till the complete healing of the lesion occurs. - Udder and teat abscess ——–

Abscess formation occurs more often on the udder than the teat. Many cases with chronicaterial.

mastitis especially due to resistant microbes suddenly develop abscessation on side of affected udder. Such cases can easily be diagnosed by puncturing the swollen part. The abscess cavity is opened for complete drainage of pus. After drainage of the pus, the cavity is dressed with tincture iodine followed by application of soothing agents until obliteration of abscess cavity. In case of necrosis of teat or udder, amputation of teat or affected quarter is recommended followed by daily dressing till complete healing of wound occurs.

4.Teat laceration and fistulae———

The condition is mostly observed in those animals that have long teats and pendulous udder. When animal tries to jump over the barbed wire or pass through the thorny bushes, their teat get teared due to laceration of skin and muscles. If this laceration is deeper, then even teat canal gets opened and milk will start flowing through the teared portion. This condition is called as teat fistula. The cases of teat fistula are considered as emergency because any delay in repair of such teat will cause development of mastitis or necrosis of the teat. For repair of such teat, all aseptic precautions should be taken into considerations. A full coverage of systematic antibiotic is required and for proper drainage Larson’s teat plug is used. Different suture techniques are used to repair the teat fistula but double layer simple continuous suturing with PGA 3/0 and in between simple vertical mattress simple interrupted suturing of skin with nylon 1/0 is found suitable for repair of teat fistula.

B. Conditions of gland and teat cistern or canal —— - Lactolith (milk stone)——-

Milk stone are formed into the teat canal when the milk is rich in minerals and salty in taste

due to super saturation of salts. The stone moves freely in teat canal and hinder the milk flow, if large in size. They usually get washed out along with ilk but if large in size then it can be crushed with small forceps or cutting the sphincter with Litchy teat knife or teat bistouries and milked out

. 2. Teat canal polyp ——-

These are small pea sized growths attached to the wall of teat canal. The polyps hinder the milking process and sometimes even block the passage of teat canal. Teat polyps can easily take out by Huges teat tumour extractor. If its location is above the teat canal thelotomy is the best method for resection of excessive tissue. Postoperative gentamicine and prednisolone infusion for five consecutive days found suitable to check infection as well as helpful in checking further growth of the polyp. - Teat spider——–

This condition is usually due to congenital absence of teat cistern or canal. It can be acquired in cases of injury, tumour or inflammation of mammary tissue resulting in formation of thin or thick membrane, situated either at the base or middle of the teat. This membranous obstruction removed by teat scissor, Huges teat tumour extractor, teat bistouries or Hudson spiral teat instrument.

4 .Fibrosis of teat canal ——-

This condition is commonly observed in most of the lactating animals where a hard fibrous cord like structure is observed in the teat. Exact cause of this condition is not clear. However, repeated trauma due to mechanical injuries, thumb milking and calf suckling are the main contributory factors. Sometimes mastitis can also result into fibrosis of quarter followed by teat canal. This fibrotic cord will obstruct the teatcanal and will create hindrance during milking. In such cases, initially hot water fomentation followed by counter irritant massage such as iodine ointment and turpentine liniment massage is very useful. In some cases it is advisable to place polythene catheter after removal of fibroid mass by Hugs teat tumour extractor. - Tumour of mammary gland ——-

These are infrequently in lactating animals however, fibro adenoma reported in heifer. The growth can be surgically removed under caudal block or local infiltration analgesia.

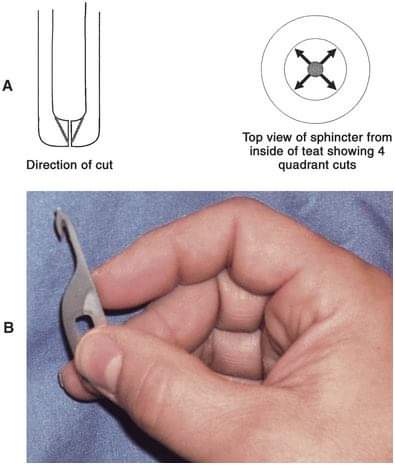

C. Conditions of teat sphincter— - Teat stenosis (Hard milker)——

It is the condition when teat sphincter gets contracted due to repeated trauma resulting in hard milking of teat. During milking one has to apply more force to take the milk out and milk will come out in fine stream. Stenosis of streak canal without acute inflammation can be treated successfully by incising the sphincter in three directions with teat knife, Bard parker blade No.11, Udall’s teat knifeMcLean teat knife. - Teat leaker ( Free milker) ——

This condition is just reverse of teat stenosis. It can be due to injury or relaxation of teat sphincter. In this case milk will go on leaking and sometimes infection may gain entry leading to mastitis. This condition is treated by injection of 0.25 ml of lugo’s iodine around the orifice or scarification and suturing with one or two stitches with monofilament nylon. - Blind teats ———-

This condition may be congenital or acquired due to any trauma near the teat sphincter. Such cases generally reported just after parturition on palpation milk thrill found in teat cistern on pressing milk passed backward toward milk udder cistern. Imperforated teat treated by 15 gauze needle, after creating opening, it is further dilated using hugs teat tumour extractor, milk canula fixed for 24 hour after that frequent milking advised at 4 to 6 hours intervals to prevent adhesion. Administration of proper antibiotics is done for a minimum period of 3-5 days.

Other Structural Disorders of the Udder

1.Trauma and Laceration:

Superficial wounds to the udder and teats may be cleaned with suitable antiseptic solutions and treated as open wounds with frequent application of antiseptic powders or sprays. If the teats are involved, adhesive tape may hasten healing. Wounds involving the teat orifice should be dressed with antiseptic creams and bandaged after milking. Affected quarters are at very high risk of infection, and prophylactic treatment with intramammary antibiotics is recommended to prevent development of mastitis.

Lacerations of the large milk vein should be considered an emergency because of the potential for severe hemorrhage; prompt compression and ligation of these lacerations is recommended.

Deeper wounds of the udder and teats should be promptly (within 6 hr) cleansed and sutured or stapled under local anesthesia with appropriate sedation and restraint. When the wound involves the teat cistern, it may be necessary to insert a self-retaining teat cannula with removable cap into the teat for the first 24 hr to prevent milk seeping through the wound (which would delay or prevent healing) and to aid in milking. The affected quarter should be infused with antibiotic preparations.

2.Teat Obstructions:

Acquired teat obstructions are usually the result of proliferation of granulation tissue after the occurrence of an observed or unobserved teat injury. Teat obstructions are usually recognized when they interfere with milk flow. They can range from diffuse, tightly adherent lesions to highly mobile discrete lesions that float throughout the gland cistern. Some “floaters” are caused by formation of small masses from butterfat, minerals, and tissue in mammary ducts during the dry period. These can be recognized by intermittent disruptions in milk flow. They may be removed by forced pressure downward on the teat cistern or by use of specialized instruments inserted through the teat canal. Membranous obstructions in the area of the annular fold at the base of the gland cistern are sometimes seen in heifers. Treatment of these obstructions is generally unsuccessful.

Complete teat obstruction may result when adhesions fill the teat cistern after severe trauma. Treatment is similar to that for stenosis but the prognosis usually is more guarded. In instances of severe injury, milking of the quarter should be permanently discontinued.

3.Teat stenosis —–

is characterized by a marked narrowing of the teat orifice or streak canal, which makes milking difficult. It usually results from a contusion or wound that produces swelling or formation of a blood clot or scab or from mastitis infections (especially in prelactating heifers). Teat obstructions can be diagnosed initially by careful palpation of the affected gland. Complex teat obstructions or obstructions in valuable animals may require diagnostic imaging such as ultrasonography, contrast radiography, or theloscopy (endoscopy).

Treatment varies depending on severity. Conservative treatment includes the use of teat cannulas and external pressure to remove obstructions, whereas serious cases may require prompt referral to specialists for thelotomy or theloscopy (endoscopic surgery). All injuries to, or surgical procedures on, the teat should be handled carefully to prevent infection. Prophylactic antibiotic infusions of the quarter are indicated when the teat or teat orifice is involved. Permanent fistulas into the teat or gland cisterns are best repaired during the dry period.

4.Bloody Milk:

The occurrence of pink- or red-tinged milk is common after calving and can be attributed to rupture of tiny mammary blood vessels. Udder swelling from edema or trauma is a potential underlying cause. Bloody milk is not fit for consumption. In most cases, it resolves without treatment in 4–14 days, provided the gland is milked out regularly. The occurrence of frank blood in a single quarter is likely the result of severe, acute mastitis or trauma, and milking should be discontinued until hemorrhage is controlled. Intramammary antibiotics should be administered if mastitis is suspected

5.Teat Sphincter Inadequacy (“Leakers” or Incontinentia Lactis):

High levels of intramammary pressure in high-producing dairy cows may result in milk dripping from teats. Risk factors for milk leakage include high peak milk flow rates, short teats, and inverted teat ends. Shorter intervals or more frequent milking may be recommended when a large proportion of the herd is affected. Occasionally, cows are observed to leak milk continuously. These cows usually have sustained a severe teat injury or have an abnormal streak canal. In general, little can be done to correct this condition, and most of these cows will develop mastitis; it is recommended that persistent leakers be designated for removal from the herd.

6.Udder Edema—-

Etiology

Udder edema, also known as “cake,” may be physiologic or pathologic. Physiologic udder edema begins several weeks before calving and is more prominent in heifers preparing to have their first calf. Many questions remain unanswered as regards the etiology of udder edema. Genetic factors certainly exist, and bull stud services sometimes grade production sires by probability of udder edema in their female offspring. Individual cows with severe or pathologic edema should be examined to rule out medical considerations that could contribute to ventral or udder edema. Some conditions to consider include cardiac conditions, caudal vena caval thrombosis, mammary vein thrombosis, and hypoproteinemia resulting from one of a number of diseases. Physical examination and serum chemistry screens may be helpful in the evaluation of such individuals.

Postparturient metritis has been associated with persistence of physiologic or pathologic udder edema by some owners and veterinarians. The pathophysiology of this relationship is unknown.

When many cows in a herd have either severe physiologic udder edema or pathologic udder edema, herd-based causes must be considered. Although feeding excessive grain to dry cows and early lactation cows has long been discussed as a cause of such endemic udder edema problems, feeding trials do not support this theory. Similarly, high protein diets do not seem to be directly involved. Currently, excessive total dietary potassium and sodium are considered possible culprits in herd-wide udder edema problems. Total intake of potassium may be excessive in some instances when high quality alfalfa haylage constitutes a major portion of the ration. Forages harvested from land that is fertilized repeatedly with manure are becoming an increasing problem because of their high potassium content. One article recommends no more than 227 g/day/head of potassium in heifers. Similarly sodium levels may be excessive when considering total available sodium in the basic ration, water, and mineral additives plus or minus free choice salt.

Hypoproteinemia and especially low albumin fractions in affected cows also may contribute to udder edema. Metabolic profiles need to be performed to assess this possibility and determine the origin.

Signs

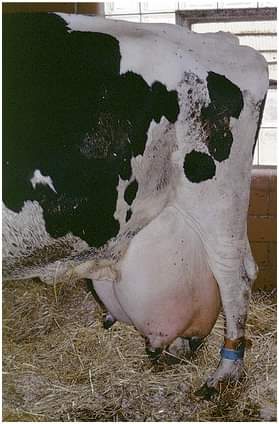

Physiologic udder edema may start in the rear udder, fore udder, in the left or right half of the udder, or symmetrically in all four quarters. Edema tends to be most prominent in the rear quarters and floor of the udder Cows with moderate to severe udder edema usually have a variable degree of ventral edema extending from the fore udder toward the brisket.

Pronounced udder edema interferes with complete milkout because it causes the affected cow discomfort, and milking may accentuate that discomfort. In addition, interstitial edema in the mammary glands may cause pressure differentials that interfere with normal production and let down of milk. Therefore chronic or pathologic edema may have a negative effect on the lactation potential because cattle never reach their projected production. Interference with complete milkout resulting from pain, as well as mechanical or pressure influences, also may lead to postmilking leakage of milk in cows with severe udder edema. This translates into an increased risk of mastitis.

Cows with udder edema do not act ill but may be uncomfortable or painful because of the swollen, edematous udder swinging as they move or from constantly being irritated by limb movement as they walk. In addition, when resting, the cow may tend to lie in lateral recumbency with the hind limbs extended to reduce body pressure on the udder.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on inspection, palpation, evaluation of milk secretions to rule out mastitis, and ruling out conditions such as udder abscess or hematoma. Pitting edema should be present, especially on the floor of the udder. Pitting edema may be evident over the entire udder in severe cases, and ventral edema frequently coexists in these instances.

Treatment

Treatment of individual preparturient or postparturient cows is indicated when edema has the potential to break down the udder support structure. Treatment also is indicated for preparturient cows having severe udder edema associated with leakage of milk from one or more teats.

Diuretics constitute the principal treatments for udder edema. Preparturient treatment of cattle with furosemide (0.5 to 1.0 mg/kg body weight) as an initial treatment followed by decreasing dosages of furosemide once or twice daily for 2 to 4 days is commonly used. Salt restriction should be considered. Premilking may be indicated in preparturient cows with severe udder edema that are leaking milk. This must be an individual decision based on the owner’s experience with premilking. Obviously if the option of premilking is selected, the newborn calf will require colostrum from another cow. Although premilking is controversial, some owners of show cattle swear by the technique to preserve udder conformation. Udder supports also may be helpful if fitted properly.

A word of warning about furosemide—urinary losses of calcium may be sufficient to increase the risk of periparturient hypocalcemia, and this should be anticipated in multiparous cows receiving multiple doses of the drug.

Parturient and postparturient cows judged to need treatment for udder edema may receive either furosemide or dexamethasone-diuretic combinations orally.

Individual cows may respond to one product better than the other, but this is impossible to predict. Furosemide seems to work well in some herds, whereas the dexamethasone-diuretic combination is superior in others. When considering dexamethasone-diuretic combinations, the veterinarian should first rule out contraindications to corticosteroid use. Udder supports and salt restriction may or may not be practical but should be considered. Nursing procedures including udder massage, more frequent milking, and mild exercise are helpful but labor intensive. Metritis should be ruled out or treated.

In herds with endemic udder edema, nutritional consultations are imperative to evaluate anion-cation balance. Total potassium, total sodium, and serum chemistry to profile affected and nonaffected cows should be performed. Diets with anionic salt supplementation and those with added antioxidants may show some tendency to diminish udder edema in affected herds. Water and availability of free choice salt or salt-mineral combinations should be included in the nutritional evaluation.

Reference-On Request