by- DR Manoranjan Nanda, Bhubaneswar.

Synonyms:

Hog Cholera, peste du porc, colera porcina, Virusschweinepest)

Definition:

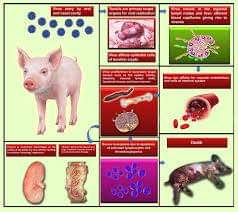

Classical Swine Fever (CSF) is a highly contagious viral disease of swine that occurs in an acute, a subacute, a chronic, or a persistent form. In the acute form, the disease is characterized by high fever, severe depression, multiple superficial and internal hemorrhages, and high morbidity and mortality. In the chronic form, the signs of depression, anorexia, and fever are less severe than in the acute form, and recovery is occasionally seen in mature animals. Transplacental infection with viral strains of low virulence often results in persistently infected piglets, which constitute a major cause of virus dissemination to noninfected farms

Classical swine fever (CSF) is a highly contagious, potentially fatal viral disease that affects pigs. This disease is a major constraint to the development of pig farming systems in Tribal population dominated states like Jharkhand, Chhatisgarh, Odissa & north east India where pig farming is a main source of livelihood for most households. About 80% of households in northeast India rear pigs and pork is a key part of the local diet.

Etiology:

Although minor antigenic variants of hog cholera virus (HCV) have been reported, there is only one serotype. Classical Swine Fever virus is a lipid-enveloped pathogen belonging to the family Flaviviridae, genus Pestivirus.

Host Range:

The hosts of Swine fever virus are the pig and wild boar.

Geographic Distribution:

According to the FAO—WHO—OIE Animal Health Yearbook 1989, Classical Swine Fever is recognized in 36 countries and is suspected of being present in another 2. The disease has been eradicated in Australia, Canada, and the United States.

Transmission:

The pig is the only natural reservoir of Classical Swine Fever. Blood, tissues, secretions and excretions from an infected animal contain Classical Swine Fever. Transmission occurs mostly by the oral route, though infection can occur through the conjunctiva, mucous membrane, skin abrasion, insemination, and percutaneous blood transfer (e.g., common needle, contaminated instruments). Airborne transmission is not thought to be important in the epizootiology of Classical Swine Fever, but such transmission could occur between mechanically ventilated units within close proximity to each other.

Introduction of infected pigs is the principal source of infection in Classical Swine Fever-free herds. Farming activities such as auction sales, livestock shows, visits by feed dealers, and rendering trucks are also potential sources of contagion. Feeding of raw or insufficiently cooked garbage is a potent source of Classical Swine Fever. During the warm season, Classical Swine Fever may be carried mechanically by insect vectors that are common to the farm environment. There is no evidence, however, that Classical Swine Fever replicates in invertebrate vectors. Husbandry methods also play an important role in Classical Swine Fever transmission. Large breeding units (100 sows) have a higher risk of recycling infection than small herds. In large breeding units where continuous farrowing is practiced, strains of low virulence may be perpetuated indefinitely until the cycle is interrupted by stamping-out procedures and a thorough cleaning and disinfection are carried out.

Incubation Period:

The incubation period is usually 3 to 4 days but can range from 2 to 14 days.

Clinical Signs:

The clinical signs of Classical Swine Fever are determined by the virulence of the strain and the susceptibility of the host pigs. Virulent strains cause the acute form of the disease, whereas strains of low virulence induce a relatively high proportion of chronic infections that may be inapparent or atypical. These strains are also responsible for the “carrier-sow” syndrome from which persistently infected piglets are produced.

Acute Classical Swine Fever:

In acute Classical Swine Fever, the pigs look and act sick. Their disease progresses to death within 10 to 15 days, and remissions are rare. In an affected herd, some pigs will become drowsy and inactive and will stand with arched backs. Other pigs will stand with drooping heads and straight tails. Some pigs may vomit a yellow fluid containing bile. The sick pigs will huddle and pile up on each other in the warmest corner of the enclosure and will rise only if prompted vigorously. Anorexia and constipation will accompany a high fever that may reach 108° F (42.2° C) with an average of 106° F (41.1° C). Pigs may continue to drink and may have diarrhea toward the end of the disease process. Conjunctivitis is frequent and is manifested by encrustation of the eyelids and the presence of dirty streaks below the eyes caused by the accumulation of dust and feed particles. Sick pigs become gaunt and have a weak, staggering gait related to posterior weakness. In terminal stages, pigs will become recumbent, and convulsions may occur shortly before death. In the terminal stage, a purplish discoloration of the skin may be seen; if present, the lesions are most numerous on the abdomen and the inner aspects of the thighs.

Chronic Classical Swine Fever:

Chronic Classical Swine Fever is characterized by prolonged and intermittent disease periods with anorexia, fever, alternating diarrhea and constipation, and alopecia. A chronically infected pig may have a disproportionately large head relative to the small trunk. These runt pigs may stand with arched backs and their hind legs placed under the body. Eventually, all chronically infected pigs will die.

Congenital Classical Swine Fever:

Congenital Classical Swine Fever infection by virulent strains will likely result in abortions or in the birth of diseased pigs that will die shortly after birth. Transplacental transmission with low-virulence strains may result in mummification, stillbirth, or the birth of weak and “shaker” pigs. Malformation of the visceral organs and of the central nervous system occurs frequently. Some pigs may be born virtually healthy but persistently infected with Classical Swine Fever. Such infection usually follows exposure of fetuses to Classical Swine Fever of low virulence in the first trimester of fetal life. Pigs thus infected do not produce neutralizing antibodies to HVC and have a lifelong viremia. The pigs may be virtually free of disease for several months before developing mild anorexia, depression, conjunctivitis, dermatitis, diarrhea, runting, and locomotive disturbance leading to paresis and death. In breeding herds affected with lowvirulence strains of Classical Swine Fever, poor reproductive performance may be the only sign of disease.

Gross Lesions:

Acute Classical Swine Fever:

The most common lesion observed in pigs dying of acute Classical Swine Fever is hemorrhage. Externally, a purplish discoloration of the skin is the first observation. There may be necrotic foci in the tonsils. Internally, the submandibular and pharyngeal lymph nodes are the first to be affected and become swollen owing to edema and hemorrhage. Because of the structure of the pig lymph node, hemorrhages are located at the periphery of the node. As the disease progresses, the hemorrhage and edema will spread to other lymph nodes. The surface of the spleen, and particularly the edge of the organ, may have raised, dark wedge-shaped areas. These are called splenic infarcts. Infarcts are frequently observed in pigs infected experimentally with older strains of Classical Swine Fever but are less commonly seen with the contemporary strains.

Pinpoint to ecchymotic hemorrhages on the surface of the kidney are very common in Classical Swine Fever. Such lesions are easier to see in the decapsulated kidney. Hemorrhages are also found on the surface of the small and large intestine, the larynx, the heart, the epiglottis, and the fascia lata of the back muscles. All serous and mucosal surfaces may have petechial or ecchymotic hemorrhages.

Accumulation of straw-colored fluids in the peritoneal and thoracic cavities and in the pericardial sac may be present.

The lungs are congested and hemorrhagic and have zones of bronchopneumonia.

Chronic Classical Swine Fever:

In chronic Classical Swine Fever, the lesions are less severe and are often complicated by secondary bacterial infections. In the large intestine, button ulcers are an expression of such a secondary bacterial infection. In growing pigs surviving for more than 30 days, lesions may be seen at the costochondral junction of the ribs and at the growth plates of long bones.

Congenital Classical Swine Fever:

In pigs infected transplacentally with Classical Swine Fever strains of low virulence, the most commonly seen lesions are hypoplasia of the cerebellum, thymus atrophy, ascites, and deformities of the head and of the limbs. Edema and petechial hemorrhages of the skin and of the internal organs are seen at the terminal stage of the disease.

Morbidity and Mortality

In acute Classical Swine Fever, the morbidity and mortality are high.

Diagnosis:

Field Diagnosis

Septicemic conditions in which pigs have high fever should be investigated carefully. A thorough history from the herd owner should be obtained to determine if raw garbage was fed, if unusual biological products were used, or if recent additions were made to the herd. Careful observation of the clinical signs and of the necropsy lesions should be recorded. In acute Classical Swine Fever, it is helpful to necropsy four or five pigs to increase the probability of observing the representative lesions.

A marked leukopenia is detectable at the time of initial rise in body temperature and persists throughout the course of the acute and chronic disease. This feature was once widely used in the field diagnosis of Classical Swine Fever. Nowadays, with the development of more specific laboratory diagnostic methods, which are aimed at demonstrating the virus or its structural antigens in tissues or at detecting specific antibodies in the serum, the white blood count is not as widely used. In endemic areas it could be helpful.

Differential Diagnosis:

Differential diagnosis of Classical Swine Fever should include African swine fever, erysipelas, salmonellosis, eperythrozoonosis, and salt poisoning.

Vaccination:

Over the years, numerous regimens of vaccination have been advocated with a variable degree of success. In the past two decades, modified live vaccines (MLV) with no residual virulence for pigs have become available. The lapinized Chinese (C) strain, the Japanese guinea pig cell culture-adapted strain, and the French Thiverval strain have been widely used. All three strains are considered innocuous for pregnant sows and piglets over 2 weeks old.

Three vaccine types are available in India Lapinized vaccine:

is developed by serial passage of CSF virus in rabbits, and the vaccine is processed from the spleen and other lymphoid tissues of the infected rabbits. The biggest limitation in the production of this vaccine is its dependence on the availability and continuous supply of rabbits. This vaccine is currently produced by the Institute of Veterinary Biologicals at Guwahati, Kolkata, Lucknow, the Institute of Animal Health and Veterinary Biologicals, Mhow and Indian Veterinary Research Institute, Izatnagar.

Lapinized cell culture vaccine: The lapinized vaccine strain is used to produce vaccine in cell culture. Production of this vaccine does not depend on availability of rabbits and can therefore be made in large quantities. This vaccine is currently produced on ‘trial basis’ by the Institute of Animal Health and Veterinary Biologicals (IAHVB) in Bangalore. Its commercial production is expected soon after licensing is received from government. It is reported that the Indian Veterinary Research Institute also has developed this technology and is working towards its commercial production. Production and use of this vaccine appears to be the best available choice. The available infrastructure in some of the veterinary biological institutes can be used for this purpose but with additional equipment and capacity strengthening. Cell culture vaccine: Local CSF virus is isolated from the field during disease outbreak and grown in cell culture and attenuated to produce the vaccine.

Control and Eradication:

In countries where Classical Swine Fever is enzootic, a systematic vaccination program is effective in preventing losses. Experience in the United States and in some countries of the European Union has proven that a strict regimen of vaccination will reduce the number of outbreaks to a level at which complete eradication by sanitary measure alone will be feasible. At that point, vaccination must be stopped. A successful eradication program requires a massive input of funds from a central government and cooperation from the government, the swine industry, and the veterinary profession. Eradication measures will be assisted by strictly enforcing the garbage cooking laws, having an effective swine identification system, and using serological surveys targeted primarily to breeding sows to detect subclinical infections.

Policy recommendation for prevention and control of CSF:

To meet the immediate demand, the lapinized vaccine production facilities at the Institute of Veterinary Biologicals in different states of India should be strengthened with infrastructure and manpower support.

Simultaneously, to meet the country’s entire demand, commercialization of the lapinized cell culture vaccine technology through public–private partnership is a next best option. In this context, the plan by the Indian Veterinary Research Institute to commercialize this technology through private firms may be strongly supported.

In the long run, the cell culture CSF vaccine should replace the lapinized cell culture vaccine and production of the latter stopped.

There is a need to strengthen the ‘cold chain facilities’ at veterinary dispensary.

State CSF surveillance units should be set up in each states directorate of Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Services and the state epidemiologist with his/ her colleagues should independently investigate all disease outbreaks supported by laboratory investigations

Reference: On the request.