TOXOPLASMOSIS IN CATS AS A FATAL ZOONOTIC DISEASE FOR PREGNANT LADY

Toxoplasmosis is an important infection caused by single celled parasite Toxoplasma gondii which is one of the world’s most common parasites. Toxoplasmosis is considered to be the third leading cause of death attributed to food-borne illness in the United States. Although in India , its prevalence is less as compared to developed countries becouse the keeping of cat as pets in India is less .Most people affected never develop signs and symptoms. But for infants born to infected mothers and for people with compromised immune systems, toxoplasmosis can cause extremely serious complications. Toxoplasmosis was first described in 1908 from a small rodent. The parasite infects almost all worm blooded animals and serological evidence indicates that it is one of the most common of humans’infections throughout the world.The disease is transmitted mainly by ingestion of infective stage of the parasite, organ transplant as well as blood transfusion in addition to the transplacental transmission which is very common. Toxoplasmosis can be presented in various forms of clinical manifestations depending on the immune status of the patient causing life threatening disease in AIDS patient. Pregnant women, cat owners, veterinarians, abattoir workers, children, cooks, butchers are considered as high risk group. Timely treatment of man and animals with proper antibiotic, hygienic measures, proper disinfection, mass education and vaccination are the measures to curtail the disease

Toxoplasma gondii is a protozoal parasite capable of infecting any warm-blooded animal, including humans.

Wild and domestic cats are the only known definitive hosts of Toxoplasma; they shed infective stages of the parasite in their feces. All other animals and humans serve as intermediate hosts in which the parasite may cause systemic infection, which typically results in the formation of tissue cysts.

In all species, Toxoplasma infection is usually subclinical, although it may occasionally

cause mild, non-specific signs. Infection may have much more serious consequences in

immunocompromised or pregnant animals and people.

The major modes of transmission include consumption of undercooked meat containing

Toxoplasma cysts, fecal-oral transfer of Toxoplasma oocysts from cat feces (either directly

or in contaminated food, water or soil), and vertical transmission from mother to

fetus if primary (i.e. first-time) infection occurs during pregnancy.

The risk of contracting Toxoplasma infection from cleaning the litter box of a

house cat is actually very small, especially if a few simple precautions such as

appropriate hand washing are observed.

Prevalence of Toxoplasma —–

Toxoplasma is one of the most widespread zoonotic pathogens in the world. In most animals and people, primary infection results in a detectable antibody titre for the life of the host, therefore seroprevalence (i.e. previous exposure to the parasite but not necessarily clinical disease) increases with age.

Humans ——

Because toxoplasmosis is not a reportable disease in Ontario and most of North America, it is difficult to estimate the prevalence of infection in animals or people. An average of 15 000 cases of clinical toxoplasmosis are reported annually in the USA, but it has been estimated that the actual number of cases is likely closer to 225 000. It is estimated that 50% of these cases occur due to foodborne transmission of Toxoplasma.

Seroprevalence in the general population in persons over 12 years of age was estimated to be 22.5% in one .North American study performed from 1988-1994. Worldwide, seroprevalence ranges from 0-100% depending on country, geographic area and even ethnic group.

Between 40 to 400 children born in Canada each year are infected with Toxoplasma before birth.

Animals –—

The prevalence of oocyst shedding in cats is very low (0-1%), even though serological studies indicate that at least 15-40% of cats have been infected, depending on how the cats are fed and whether they go outdoors. Disease and exposure are more common in cats and other pets that go outdoors, hunt, or are fed raw meat.

Zoonotic Risk & Other Risk Factors ——

The risk of transmission of Toxoplasma from a household cat can be easily controlled by means of simple infectious disease control procedures (see Infection Control below). In one study from Norway, cleaning a cat litter box was found to be a strong risk factor for exposure to Toxoplasma. However the same study, and another European study, showed no association between Toxoplasma exposure and living with or near a cat.

Contamination of water sources and soil with the feces of wild or

domestic cats is more difficult to control, and can lead to infection

following ingestion of oocysts on unwashed, uncooked vegetables or in

contaminated water. The largest human outbreak of toxoplasmosis ever

reported occurred in Victoria, BC in 1995, and was attributed to fecal

contamination of the water supply from domestic and wild cats.

Cockroaches and flies may also transfer Toxoplasma oocysts from cat

feces to food, water, utensils or other surfaces.

Contact with contaminated soil or sand, such as in a garden or a

sandbox, may also be associated with Toxoplasma infection.

Consumption of undercooked meat is one of the principle risk factors for

Toxoplasma infection. The importance of these various risk factors likely varies considerably between ethnic groups due to differences in cultural habits regarding exposure to undercooked meat, soil and cats.

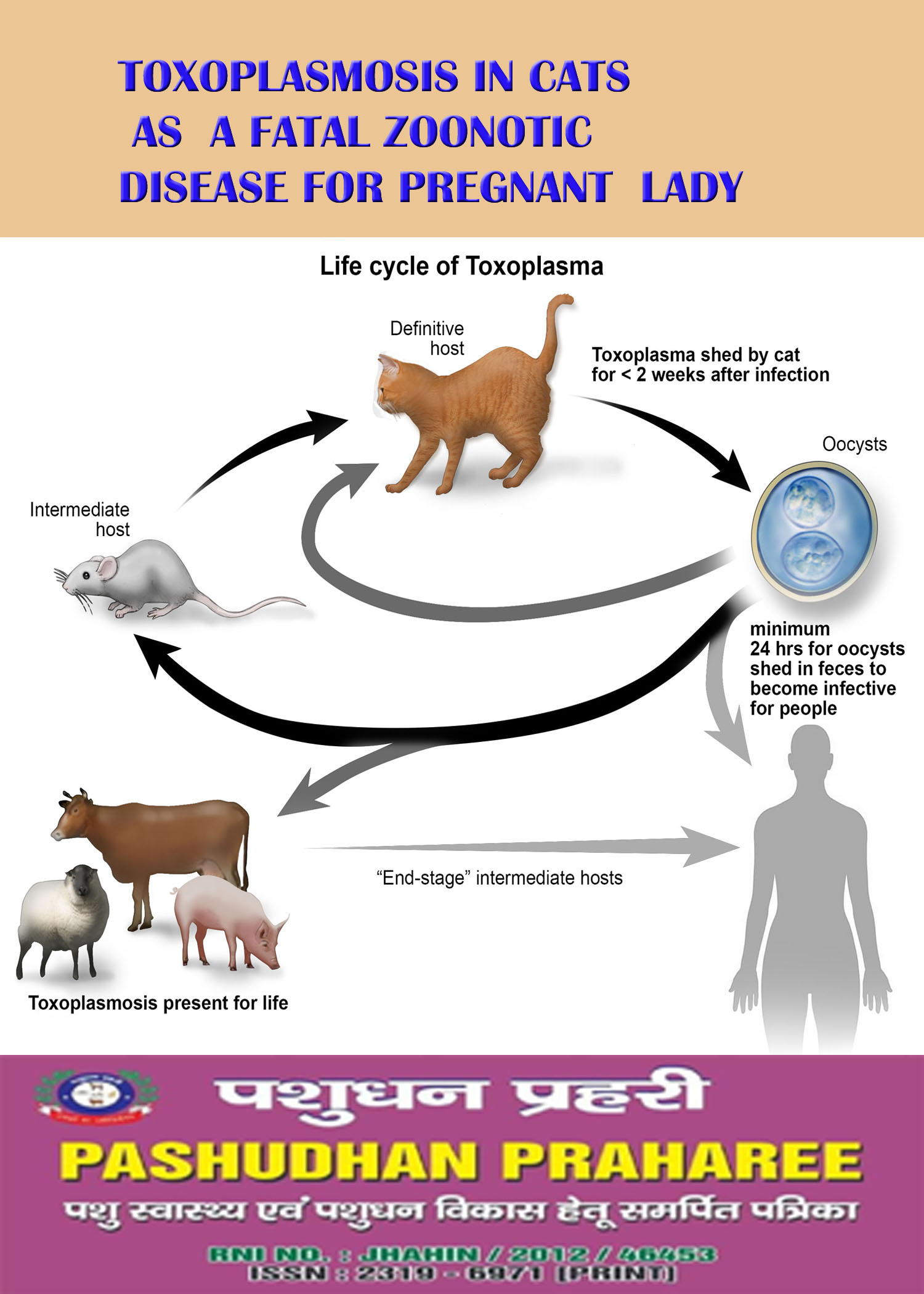

Life Cycle of Toxoplasma——-

—–

Unsporulated oocysts of Toxoplasma are passed in

the feces of acutely infected cats. The oocysts usually

sporulate (forming sporozoites) in 1-5 days, and are

then infective when ingested by any warm-blooded

host. In the intestine, the sporozoites excyst, invade

intestinal cells and begin to divide to produce

tachyzoites. These then migrate throughout the body,

invading and destroying tissue cells as they multiply.

Eventually the tachyzoites become bradyzoites, which

then form microscopic cysts within cells of the central

nervous system, muscle, and sometimes other organs.

The cysts typically persist until death of the host

without causing clinical signs. If the host is eaten by

another animal, the bradyzoites excyst in

the intestine and the process is repeated, forming tissue cysts in the new host.

If a tissue cyst is eaten by a cat, the

bradyzoites invade the intestinal epithelial

cells and undergo a different series of divisions, forming meronts, and finally microgametes and macrogametocytes all within the intestinal wall. The microgametes fertilize the macrogametocytes. These then form a resistant wall to become unsporulated oocysts which are passed in the feces of the cat.

When fed tissue cysts, approximately 97% of cats infected for the first time will produce oocysts, usually within 3-10 days. They may shed for up to 20 days, but the majority of oocysts will be shed in just 1-2 days. Only 20% of cats fed oocysts will develop a patent infection, and the prepatent period may be 18 days or more. Contrary to previous

beliefs, studies have shown that oocysts can be shed in low numbers by previously infected cats that are challenged again with the parasite or that become immunosuppressed due to disease or drug therapy.

Transmission of Toxoplasma –—–

Carnivorous animals are often infected with Toxoplasma through ingestion of bradyzoites from tissue cysts in infected prey, as are people who eat undercooked meat, particularly that of pigs, sheep and goats. Toxoplasma cysts are less commonly found in poultry and rarely found in beef. The prevalence of Toxoplasma infection in commercial farm animals has decreased significantly with the advent of intensive management practices. Free-

range poultry, swine and small ruminants, marsupials (e.g. kangaroos) and some wild game are more likely to harbour cysts.

Oocysts are only shed by cats. Unsporulated oocysts in fresh feces are not infective; they need appropriate oxygen, humidity and temperature to sporulate. Sporulated oocysts are the most environmentally resistant life stage of the parasite. Ingestion of as few as ten oocysts may infect an intermediate host, while ingestion of 100 or more oocysts can cause a patent infection in a cat, which may shed tens to hundreds of millions of oocysts.

Tachyzoites are potentially infective, and may be found in the tissues of acutely infected animals, as well as the milk of sheep, goats, cows, and sometimes chicken eggs. However, tachyzoites are killed relatively easily by pasteurization, and uncommonly survive gastric digestion, although this may be more of a concern in infants who have lower concentrations of peptic enzymes. Any kind of cooking will kill tachyzoites in an egg. Toxoplasmosis can also be transmitted by organ transplants and blood transfusions, but this is uncommon.

In utero transmission of Toxoplasma occurs only if primary infection of the dam/mother occurs during pregnancy. Parasitemia then results in placentitis and infection of the fetus. This is more likely to occur in humans, sheep and goats, and sometimes in mice, cats and dogs. Under normal circumstances, a female that has been exposed to Toxoplasma 4-6 months prior to pregnancy will develop sufficient immunity to protect herself and the fetus for the rest of her life. However, if the immune response is suppressed by drug therapy or disease such as HIV/AIDS in humans, both the mother and the fetus may become susceptible to infection again. In humans, the risk of the infection being passed on to the fetus increases from the first trimester (10-25%) to the third trimester (60-90%). However, the potential congenital defects are more severe with earlier infections.

Symptoms and Signs ——

Clinical signs of toxoplasmosis are caused by cellular destruction due to multiplying tachyzoites, which most commonly affect the brain, liver, lungs, skeletal muscle and eyes. Oocyst-induced infection may be more severe than that induced by ingestion of tissue cysts. Infection may be associated with other diseases such as HIV/AIDS in humans or immunosuppressive therapy in any species.

How do people get toxoplasmosis?

A Toxoplasma infection occurs by:

Eating undercooked, contaminated meat (especially pork, lamb, and venison).

Accidental ingestion of undercooked, contaminated meat after handling it and not washing hands thoroughly (Toxoplasma cannot be absorbed through intact skin).

Eating food that was contaminated by knives, utensils, cutting boards and other foods that have had contact with raw, contaminated meat.

Drinking water contaminated with Toxoplasma gondii.

Accidentally swallowing the parasite through contact with cat feces that contain Toxoplasma. This might happen by cleaning a cat’s litter box when the cat has shed Toxoplasma in its feces touching or ingesting anything that has come into contact with cat feces that contain Toxoplasma accidentally ingesting contaminated soil (e.g., not washing hands after gardening or eating unwashed fruits or vegetables from a garden)

Mother-to-child (congenital) transmission.

Receiving an infected organ transplant or infected blood via transfusion, though this is rare.

What are the signs and symptoms of toxoplasmosis?

Symptoms of the infection vary.

Most people who become infected with Toxoplasma gondii are not aware of it.

Some people who have toxoplasmosis may feel as if they have the “flu” with swollen lymph glands or muscle aches and pains that last for a month or more.

Severe toxoplasmosis, causing damage to the brain, eyes, or other organs, can develop from an acute Toxoplasma infection or one that had occurred earlier in life and is now reactivated. Severe cases are more likely in individuals who have weak immune systems, though occasionally, even persons with healthy immune systems may experience eye damage from toxoplasmosis.

Signs and symptoms of ocular toxoplasmosis can include reduced vision, blurred vision, pain (often with bright light), redness of the eye, and sometimes tearing. Ophthalmologists sometimes prescribe medicine to treat active disease. Whether or not medication is recommended depends on the size of the eye lesion, the location, and the characteristics of the lesion (acute active, versus chronic not progressing). An ophthalmologist will provide the best care for ocular toxoplasmosis.

Most infants who are infected while still in the womb have no symptoms at birth, but they may develop symptoms later in life. A small percentage of infected newborns have serious eye or brain damage at birth.

Humans: –—-

Approximately 15% of cases of Toxoplasma infection are associated with clinical signs such as mild fever and lymphadenopathy, and may appear similar to mononucleosis or Hodgkin disease.

Signs may persist for 1 to 12 weeks; more severe disease is very rare in immunocompetent individuals. Of clinical cases, 0.2%-0.7% may develop ocular toxoplasmosis (retinitis), but this is more commonly associated with congenital infection. If more severe disease develops, signs may be related to encephalitis, hepatitis, myositis or pneumonia. Worldwide, Toxoplasma encephalitis develops at some time in approximately 40% of individuals with AIDS, and is fatal in 10-30% of these cases. Individuals with low CD4 counts and high Toxoplasma titres are therefore often treated prophylactically for the disease with high-dose trimethoprim-sulfonamide combinations.

Approximately 10% of congenital Toxoplasma infections result in abortion or neonatal death. In 10-23% of congenital infections, signs are present at birth; these may include hydrocephalus, chorioretinitis, hepatosplenomegally, microcephally, and small size. Clinical signs of congenital Toxoplasma infection are not apparent at first in 67-80% of cases. Ocular toxoplasmosis may occur in up to 1/3 of children that survive congenital infection.

Animals: ——-

In dogs and cats, primary systemic infection with Toxoplasma is typically either

subclinical or may cause mild fever and lymphadenopathy. In rare cases when

significant clinical disease develops, signs may include fever, lethargy, anorexia,

and others signs associated with pneumonia, hepatitis, myositis or encephalitis.

The onset of signs may be slow, or the disease may be rapidly fatal. Ocular

lesions are much more common in cats than in dogs. Kittens and puppies are

often severely affected and may be stillborn or die before weaning.

Clinical infection in sheep and goats is much more common than in dogs and

cats, and is primarily associated with reproductive problems, including abortion

and birth of weak, uncoordinated young. The infection can also be common in

birds, but it is rarely clinical.

Diagnosis ——

Once infected with Toxoplasma, people and animals usually develop a life-long protective antibody titre, unless the individual is severely immunocompromised and unable to mount or sustain an appropriate humoral immune response. The organism itself can be detected in tissues or body fluids using either polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or bioassays in mice.

Humans: ——

There are several different serological tests used to diagnose toxoplasmosis in

humans that are intended to help differentiate between latent and acute

infections. Serum IgM titres indicate recent infection, whereas serum IgG titres

persist longer and therefore typically indicate previous infection. However, both

types of antibodies are usually detectable within 1-2 weeks of infection.

Some Toxoplasma IgM test kits have relatively high false-positive rates, and

results must therefore be interpreted carefully.

Measurement of IgG avidity can also help “age” the antibody response.

The modified latex agglutination test (MAT) detects IgG, but can help

differentiate acute and chronic infections based on reactivity with acetone versus formalin-fixed antigen. It is considered extremely sensitive.

Serological screening of pregnant women is not generally recommended in the USA and Canada, as it is in some

European countries such as Belgium and France, because the risk of exposure to Toxoplasma is comparatively low.

Diagnosis of in utero infection is most commonly accomplished by detecting Toxoplasma DNA in amniotic fluid

using PCR. A positive test should be followed up by a fetal ultrasonographic examination to look for physical

congenital defects.

Animals: —–

Compared to humans, development and persistence of IgM in

systemically infected cats is very inconsistent, and is not a reliable

marker of acute Toxoplasma infection. Furthermore, some cats may

not develop IgG titres until 4-6 weeks after infection, well after they

have stopped shedding oocysts, and the titre may peak in as little as

2-3 weeks and remain high for years.

A cat that is IgG seropositive is unlikely to be shedding oocysts,

and is unlikely to shed oocysts if it is exposed to the parasite.

Nonetheless, exposure should be minimized as some seropositive

cats may shed low numbers of oocysts if re-exposed. A cat that is

seronegative is unlikely to be shedding oocysts, but is likely to

develop a patent infection if it is exposed to Toxoplasma.

Cats typically only shed oocysts in their feces for 1-3 weeks

following their first exposure to Toxoplasma, therefore fecal examination is usually unrewarding.

Treatment of Toxoplasmosis ——

Humans: —-

Traditional drug therapy for clinical toxoplasmosis consists of a combination of pyrimethamine and

sulfonamides. Spiramycin is one of the current drugs of choice for treatment of pregnant women. It is readily

available in Europe, but must be purchased from the manufacturer in the USA.

Since the effectiveness of drug therapy for toxoplasmosis during pregnancy is actually unknown, the

cost effectiveness of such therapy is often debated. Treatment may decrease the severity of

congenital toxoplasmosis or long term consequences, but possibly not the risk of transmission.

Early treatment of prenatally infected children has been shown to reduce or prevent clinical problems later in

life, therefore neonatal screening programs, particularly those that are piggy-backed on existing screening

programs for disease such as phenylketonuria, can be quite cost effective.

Transplant patients (especially heart transplant patients) should be treated prophylactically with antimicrobials

for six weeks to help prevent infection following the operation.

Antimicrobial prophylaxis is also recommended to prevent reactivation of infection from encysted bradyzoites in

patients who develop HIV/AIDS and have had a high antibody titre to Toxoplasma.

Animals: Clindamycin and pyrimethamine/sulfonamide combinations are typically used to treat clinical

toxoplasmosis in dogs and cats. The same drugs, as well as anticoccidials such as monensin and toltrazuril can be

used to help decrease oocyst shedding in cats if the animal is exposed to the parasite or becomes

immunosuppressed. An oral vaccine to reduce oocyst shedding in cats has been developed, but is not currently

commercially available.

Infection Control ——

In the majority of studies, no direct association has been found between cat

ownership and the risk of toxoplasmosis in people. Given the emotional

benefits associated with owning a cat, and the minimal risk of transmission of

Toxoplasma if appropriate hygiene is practiced, even immunocompromised or

pregnant individuals do NOT need to give up their cats.

Such individuals should avoid contact with cat feces and cat litter whenever

possible by having someone else clean their cat’s litter box.

If a cat is found to be shedding oocysts, it should be removed from the premises

temporarily and treated to eliminate shedding. Because cats are usually

meticulous groomers, it is unlikely that oocysts will be found on their fur, so regular

handling is not a significant risk.

Always wash your hands thoroughly after contact with cat stool, litter or a litter box. ƒ Microwave cooking, salting and smoking do not consistently kill all infective Toxoplasma

organisms. Freezing meat to -12ºC for at least 24 hours will kill most Toxoplasma tissue

cysts, but sporulated oocysts can survive at -20ºC for up to 28 days.

Washing kitchen utensils and surfaces that have come in contact with raw meat with soap

and scalding hot water (>70ºC) will kill any bradyzoites or tachyzoites present.

Oocysts take longer to sporulate under cooler conditions. For example, at room temperature sporulation may

occur within 1-5 days, but it may take 3 weeks at 11ºC.

Once sporulated, oocysts can survive even longer in the environment. They are resistant to most disinfectants,

therefore immersion of litter boxes and other potentially contaminated instruments in boiling or scalding water is

the preferred means of decontamination. Even sporulated oocysts are killed by heating to 55-60ºC for 1-2

minutes.

Cat feces should be disposed of daily to reduce the risk of

transmission. Feces and dirty litter can be disposed of in a

septic system if the litter is biodegradable, sealed tightly in a

plastic bag and placed in the garbage, or incinerated. Backyard

compost units do not produce sufficient heat to destroy oocysts

and other pathogens potentially present in fecal material.

Keep cats out of sandboxes (e.g. cover sandboxes when not in

use) and other areas where children play that cats may be

inclined to defecate.

Pregnant Women and Individuals with Compromised Immune Systems: —-

Education of individuals in these high risk groups about how to decrease the transmission of Toxoplasma is an

important tool in the prevention of this disease. The following recommendations are particularly important for these individuals, but also apply to the prevention of toxoplasmosis in general:

Cook all meat to a minimum internal temperature of 67ºC/153ºF.

Peel or thoroughly wash fruit and vegetables prior to consumption.

Clean all surfaces and objects that come in contact with raw meat or unwashed fruit and vegetables.

Avoid contact with cat litter and garden soil, otherwise wear gloves and wash hands thoroughly after. Avoid feeding raw meat to cats.

Keep cats indoors so they do not become infected by eating small prey.

How can human infection be avoided?—

Although cats are essential to complete the life-cycle of T. gondii, numerous surveys have shown that people who own cats are not themselves at a higher risk of acquiring infection. There are several reasons for this:

1. Many pet cats will never be exposed to Toxoplasma and therefore cannot pass infection on to humans.

2. Even if a cat does become infected with Toxoplasma, it will only shed the oocysts or eggs in its faeces for a short period, approximately ten days, after initial exposure. Following this there is no further significant oocyst shedding and therefore again no further risk to humans.

3. Although humans may become infected through exposure to, and ingestion of oocysts in the environment, a more common source of infection appears to be infected meat.

Following a few sensible environmental and meat hygiene measures can greatly reduce the risk of human infection:

• Cook all meat thoroughly – at least 70 -82°C throughout.

• Wash hands, utensils and surfaces carefully before and after handling raw meat.

• Wash all fruit and vegetables carefully.

• Wear gloves when gardening in soil potentially contaminated by cat faeces.

• Empty cat litter trays daily, dispose of litter carefully, and disinfect with boiling water. If this is done every day, even if a cat is excreting oocysts, they will not have become infectious by the time the litter is changed. It takes more than twenty-four hours from when they are passed in the faeces for the oocysts to develop into the infective stage.

• Pregnant women should refrain from cleaning litter trays, if this is not possible, gloves should be worn and hands thoroughly cleaned afterwards.

• Discourage pet cats from hunting, and avoid feeding them raw or undercooked meat.

• Cover any children’s sand boxes to prevent cats using them as a litterbox.

Compiled & Shared by- Team, LITD (Livestock Institute of Training & Development) Image-Courtesy-Google Reference-On Request.