Utilization of Dead Poultry Birds as Feed Source for Animals

Vijayalaxmi I.M*1., Kotresh Prasad C2., John Abraham3, Gouri M.D1., Vivek M. Patil1

1Veterinary college, Bengaluru, 3College of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, Pookode (Kerala), 2University of Agricultural Sciences, Raichur (Karnataka)

*M.V.Sc. scholar

Department of Livestock Production Management

Veterinary College, Bengaluru

In the past twenty years, the commercial poultry business in India has undergone an unparalleled transition relative to all other animal husbandry sectors. The number of commercial poultry birds expanded from roughly “0” in the 1950s to 530.74 million in 2019. The broiler sector experienced an absolutely remarkable expansion, going from a meagre 20 million chickens in the 1960s to 3000 million birds now (Mehta and Nambiar, 2010). India ranks fifth among nations that produce chicken and third among those that produce eggs (BAHS, 2016).

The normal mortality (due to physical causes) in these farms account for about 6000 dead birds (about 8000 Kg of carcass) available per day for disposal. Chandrasekaran (2010) estimated that the total weight of the dead birds available in India was about 2.4 lakh tons per annum. As such, this huge quantity of dead birds, unless disposed of properly pose a catastrophic threat to the environment and may result in major health hazards to human as well as livestock in the wake of emerging diseases. Rendering is a great way to recycle a troublesome waste material (dead birds) into a useful feed ingredient among the various biosecure and hygienic disposal techniques (Bell, 2002). Due to the high cooking temperature of up to 140 °C under positive steam pressure, which eliminates all dangerous bacteria and their spores, it is the method that is the most bio safe (Pearson and Dutson, 1992). Carcass meal and extracted chicken oil are the by-products. You can use carcass meal as fertiliser as an ingredient in feed (Bell, 2002). However, the rendered chicken oil, which has a high amount of free fatty acids, is now of little commercial worth. In addition to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, turning discarded chicken oil into biodiesel could provide poultry farmers with new opportunities to make money from waste (John, 2012). Consequently, a study was conducted to evaluate the use of deceased chicken birds for the manufacture of biodiesel (John, 2012). Carcass meal can be used as feed ingredient and fertilizer.

Due to the growth in farm size and population, the disposal of on-farm mortality is a significant challenge in commercial poultry production. One of the most crucial components of bio-security measures in poultry farms is the regular disposal of dead birds. Because they can’t stop ground water or surface water pollution or odour nuisance, traditional disposal techniques including burial, incineration, and usage of disposal pits are no longer seen as environmentally acceptable (Bell, 2002, John, 2012). Composting, rendering, lactic fermentation, extrusion, alkaline hydrolysis, and pyrolysis are the current techniques for on-farm disposal and utilisation of poultry carcasses while meeting biosecurity and hygienic standards (Sivakumar, 2006).

In India, livestock feed production is primarily dependent on grains, according to Robinson (2010), which causes animals, particularly chickens, pigs, and fish to compete with people for grains and cereals. 13 million tonnes of animal feed material might be replaced by turning slaughterhouse waste and dead animals into meat and bone meal.

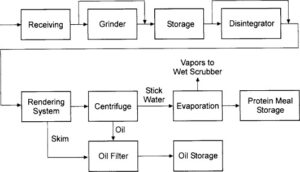

Rendering

The rendering plant is a vital link between the poultry growers and industries which use fat and oils. It can cause minimal risk with proper restrictions and sanitary precautions (Bell, 2002). Blake and Donald (1995) stated that rendering would be a viable option if carcass deterioration could be minimised and between farm bio-security maintained. The main carcass rendering processes include size reduction followed by cooking and separation of fat, water and protein materials. The techniques used include mechanical (grinding, mixing, pressing, decanting, sequential centrifugation and separating); thermal (cooking, evaporating and drying); and in some instance, chemical processes (solvent extraction) (John, 2012).

One of the finest methods for recycling farm-grown poultry carcasses is rendering, and turning carcasses into a protein by-product meal is acceptable for the environment (CAST, 2008). The process of rendering poultry mortalities involves converting carcasses into a variety of products, including water, fat, and hydrolyzed whole poultry meal. Modern processing techniques that use hydrolysis with high temperature and pressure yield hydrolyzed whole poultry meal. These techniques disintegrate entire dead, undecomposed poultry carcasses, including feathers, heads, feet, guts, unhatched eggs, blood, and other particular carcass components. As part of the manufacturing process, the poultry carcasses may be fermented or subjected to acid or alkaline treatment (AAFCO, 2006). The resulting meal and fat obtained from hydrolyzed whole poultry are suitable as animal feed ingredients and are approved for use by the Food and Drug Administration, U.S.A (Anderson, 2006).

Carcass meal yield from dead birds

One of the biggest issues that poultry meat and egg production facilities deal with on a daily basis is the disposal of carcasses, which is an ongoing task as more and more birds die from diseases, accidents, equipment failures, and natural disasters. By the end of a growing cycle, on-farm death losses (mortalities), can produce a sizable number of carcasses. As an illustration, a flock of 50,000 broilers raised to the age of 49 days (d) with an average daily mortality rate of 0.1% (4.9% overall mortality) will result in roughly 2.18 tonnes (2.4 tonnes) of carcasses (Blake et al. 1990).

According to Kulkarni et al. (2006), batch dry rendering of complete dead chicken birds produced a carcass meal yield of 35.6%. According to Karthik (2007), the average output of spent hen meal during dry rendering was 31.76%. He also noted that the feathers had totally hydrolyzed and that the colour and aroma of the meal were both golden brown and meaty. Rajendra Kumar (2009) conducted dry rendering studies with spent hen and obtained an average yield of 30.77% of spent hen meal.

Nutrient composition of poultry carcass meal:

According to Kulkarni et al. (2006), the approximate composition of poultry carcass meal was 8.5% moisture, 60.9% crude protein, 0.54% crude fibre, 10% ether extract, 0.71% sand and silica, 13.16% total ash, 0.53% salt, 3.63% calcium, and 2.15% phosphorus. The moisture, crude protein, ether extract, phosphorus, calcium, total ash, and NFE of spent hen meal were found to be 8.9, 62.24, 10.91, 0.74, 12.05, 3.54, 1.58, and 14.07%, respectively, according to Rajendra Kumar’s (2009). According to John and Ramesh (2014), centrifugal fat extraction produces poultry carcass meal with the following proximate composition: moisture 8.88 0.06%, crude protein 61.96 0.60%, ether extract 10.93 0.26%, crude fibre 0.67 0.18%, and nitrogen Free Extract 5.12 ± 0.59%, total ash 12.44 ± 0.58% and meal obtained by solvent extraction method contain moisture 6.92 ± 0.14%, Crude Protein 71.23 ± 0.75 %, Ether Extract 0.83 ± 0.02%, Crude Fiber 0.95 ± 0.04%, Nitrogen Free Extract 8.70 ± 0.64%, total ash 11.37 ± 0.41%. Application of heat to meat meal (MM) during the dry rendering helps to decrease the rumen degradability of protein in ruminant.

Utilization of poultry carcass meal in goat feed

Trimmings from the slaughter of animals and dead poultry birds are used to make meat meal. Hair, hoof, horn, feather, manure, and stomach contents should not be included in meat meals. A good source of protein is meat meals, which include 50–55 percent high-quality protein. Meal is classified as meat and bone meal if it contains more than 4.4% phosphorus. The amount of protein in the meal changes depending on how much bone is present. Meat meal is included in the diet at a level of 7–10%. According to Lira-Casas et al. (2014), feedlot hair lambs’ growth performance and some carcass parameters were improved when 2.5% of BM was added to the finishing meal made out of cereal grains.

The weight gain (kg) and average daily gain (g) among the Malabari kids fed different creep diets were considerably different, according to Bhale (2015), who studied the kids raised on natural suckling (T1), conventional creep feeding (T2), and unconventional creep feeding (T3). At weaning, the body weight of Malabari kids who were provided only milk and green grass until they were three months old was 7.25 ± 0.13 kg, while it was 8.24 ± 0.35 kg and 10.87 ± 0.48 kg for those who were fed standard creep diet and unconventional creep ration, respectively. When compared to kids of T1, which had an FCR of 4.62, kids in T3 and T2 had a considerably (P<0.01) higher FCR of 3.14 and 4.40, respectively.

In comparison to commercial pellets, concentrated feeding can increase Malabari kids live weight gains by 50% during the post-weaning period. During the post-weaning phase, starter feed including soy bean and gingelly oil cake as the primary protein source was more expensive than starter feed incorporating chicken carcass meal as the primary protein source. It is vital to create cost-effective rations utilizing alternative feed without compromising animal health and production because the price of conventional feed ingredients is threatening global food security (Prasad et al., 2015). Poultry carcass meal is a cheap and sterile alternative to expensive conventional protein sources and can be added to the diet of ruminants and has a greater crude protein content than oil cakes and vegetable protein sources (Ramesh et al., 2014; Bhale, 2015; Prasad et al., 2015).

References:

Ananth, M.K. 2011. TN poultry industry plans ten per cent expansion in 2011-12. The Hindu Daily, 26th April, 2011.

Anderson, D. P. 2006. Rendering operations. Essential Rendering-All about the animal by-product Industry. National Renders Association: 31-52.

Bell, D. D. 2002. Waste Management. In: Commercial Chicken Meat and Egg Production 5th Edition. Springer. Chapter 1: 162-

Bhale, V.T. 2015. Effect of pre-weaning feeding management on the growth performance of Malabari kids. M.V.Sc thesis, Kerala Veterinary and Animal Sciences University,

Bohnert, D.W, Larson, B.T, Bauer, M.L, Branco, A.F, Mcleod, K.R, Harmon, D.L. And Mitchel, G.E. 1996: Nutritional evaluation of poultry by-product meal as a protein source for ruminants : small intestinal amino acid flow and disappearance in steers. J. Anim. Sci. 7: 100-107.

Chandrasekaran, D. 2010. Poultry Waste Management-Situation in India. In: Training manual of the ICAR Summer School on “Wealth from Waste of Poultry Farm, Livestock Farm and Poultry Meat Processing Plants,” held at Veterinary College and Research Institute, Namakkal, Tamil Nadu Veterinary and Animal Sciences University from 22nd Septermber 2010 to 12th October 2010: 10-13.

Council for Agricultural Science and Technology (CAST). 2008. Poultry Carcass Disposal Options for Routine and Catastrophic Mortality. Issue Paper 40. CAST, Ames, Iowa.

John Abraham, 2012. Utilization of dead poultry birds for biodiesel production- PhD Thesis submitted to the Tamil Nadu Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, Chennai.

John, A. and Ramesh, S.V. 2014. Effect of two methods of fat extraction on one proximate composition of poultry carcass meal. Indian Vet. J. 91(3): 16-18.

Karthik, P. 2007. Studies on the preparation of spent hen meal and its utilization in pet dogs. M.V.Sc., Thesis submitted to the Tamil Nadu Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, Chennai, India.

Kulkarni, V.V., Sivkumar, K., Chandirasekaran, V. and Karthic, P. 2006. Dry rendering of dead layer chickens. Compendium of the National Symposium on prospects and challenges in Indian meat industry, held at Madras Veterinary College, Chennai, India on 28-29. July, 2006: 123-126.

Lira-Casas, R., Hernández-Calva L.M., García-Juárez, G., Salinas-Chavira, J., Ortiz-Morales, O. and Suárez-González, G. 2014. Effects of broiler-meat meal on performance and carcass characteristics of crossbred hair lambs. J Anim & Plant Sci 24(6): 168-1672.

Mehta, R., Nambiar, R.G., 2010. The Poultry Industry in India. Livestock Industrialization, Trade and Social-Health, Environmental impact in Developing Countries, A Case Study [Accessed on 06.02.2014] at http://www.fao.org/AG/againinfo/home/events

Pearson, A.M and T. R. Dutson, 1992. Inedible meat by-products. Advances in Meat Research, Vol 8. Elsevier Applied Science: 113-119.

Pookode.Blake, J. P and J. O. Donald, 1995. Rendering a disposal method for dead birds (circular ANR 923). [Accessed on 03.02.2012] at http://www.aces.edu/pubs/Alabama: Auburn University and Alabama University Cooperative Extension Service.

Prasad, C., John Abraham., Jose, R. A., Raseel, K.,Balusami, C., Sunanda, C., and Muhammed Asif, M. 2015. Utilization of poultry carcass meal as a protein source in goat feed, 25th Swadeshi science congress – a national seminar, 16-18 December 2015, Sree Sankaracharya University of Sanskrit Kalady, Ernakulam, Kerala. Pp 31-33.

Prasad, C.K., John Abraham and Balusami, C. 2015. Economics of replacing conventional protein source with poultry carcass meal in grower Malabari kids. Indian Journal of Veterinary and Animal Sciences Research. 44(6): 416-420.

Rajendra Kumar, K. 2009. Studies on preparation of pet food incorporating dry rendered spent hen meal. Assesment of it storage stability and acceptability in pet dogs. M.V.Sc., Thesis, Tamil Nadu Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, Chennai, India.

Robinson, J. J. A. 2010. Livestock Waste Utilization Scenario. Training manual of the ICAR Summer School on “Wealth from Waste of Poultry Farm, Livestock Farm and Poultry Meat Processing Plants.” held at Veterinary College and Research Institute, Namakkal, Tamil Nadu Veterinary and Animal Sciences University from 22nd September 2010 to 12th October 2010: 5-9.

Sivakumar, K., 2006. Disposal and utilisation of poultry carcasses by aerobic composting. PhD Thesis submitted to the Tamil Nadu Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, Chennai.

Figure 1 Dead poultry birds (Source: Dr. John Abraham, CVAS, Pookode, Kerala)

Figure 2 Carcass meal (Source: Dr. John Abraham, CVAS, Pookode, Kerala)

Figure 3 Carcass meal (Source: https://susheela.in/poultry-meal/)

Figure 4 Rendering process (Source: Wastes from Industries (Case Studies))